A Body in Need of a Home

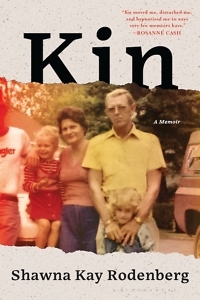

Shawna Kay Rodenberg reveals the complicated lives of rural-born women in Kin

Shawna Kay Rodenberg’s family moved a lot when she was growing up. From Seco, Kentucky, to Grand Marias, Minnesota, to Duluth, Indiana, Rodenberg’s memoir Kin recounts their travels, detailing her own story and her family’s, as well.

With a narrative so complex that one occasionally wishes for the aid of a family tree or a detailed timeline, Kin shifts between Rodenberg’s early years and the early years of her parents and close relatives. In the prologue, set in 2017, Rodenberg describes smuggling “two ounces of primo marijuana” to her father in Seco while simultaneously serving as a local tour guide for a CBS crew in town to craft “a news segment on the proposition of school choice in Appalachia.”

From here, we are whisked back in time to 1978 in Grand Marias, where young Rodenberg and her family are living on a farm, practicing a frugality so extreme that it resembles voluntary poverty. As Rodenberg writes, “The Bible was clear that people who collected too much stuff on earth were idol-worshippers, in love with the carnal world and at best only halfway committed to the Kingdom of God.” Her parents chose to leave behind jobs, a house, and most of their worldly possessions to join a community named The Body “because Christ is the head and the church is the body of God’s spotless bride.” Expected to live without toys, books, or many clothes, Rodenberg and her younger sister Misti wake early to a cold, empty room, dress and bathe themselves, then make their way to the communal kitchen for breakfast.

Rodenberg’s mother, Deborah, disagreed with many of the strict beliefs and practices of The Body, but her father, Roy, who was only 27 at the time, firmly “believed in the inevitable, biblical persecution of people who followed Christ, and took any disapproval as further proof that we were where we belonged.” It is here that young Shawna is first exposed to unwanted sexual attention from boys and older men alike, and where she begins to question whether she was born with an inherent wrongness inside that drives her to be ashamed of herself for decades.

The rest of the memoir alternates between chapters from Rodenberg’s own story and chapters devoted to the stories of people in her life, such as her mother, father, and several aunts. Rodenberg’s voice often disappears inside her own memoir, becoming a fly on the wall to chronicle the lives of others in her family. This unique — and oftentimes jarring — splintering of perspective further elucidates the feeling of being lost, confused, and powerless in the face of the larger narrative that surrounds and confines many rural-born women in Appalachia. Enmeshed in a loop of poverty, early motherhood, limited or nonexistent access to education, as well as a hostile environment of brutal and abusive relatives, most women in Rodenberg’s history felt they had to marry or move far away to pull themselves out of the situation they were born into.

Though Rodenberg lived for several years in The Body, her family gradually drifted from the community’s farm, first taking a job that came with a house in Duluth, where Rodenberg’s parents were live-in caregivers for several ill women of The Body. Her mother did not like the close proximity to the women, but Rodenberg was ecstatic to return to a sense of normalcy — a life that came with public school and a slackening of the strict rules that governed communal life on the farm. After Duluth, the family job-hopped until they found themselves back in Seco, Kentucky, building a house on a hill right below the home of Rodenberg’s grandparents, who were excited for their return.

Though Rodenberg lived for several years in The Body, her family gradually drifted from the community’s farm, first taking a job that came with a house in Duluth, where Rodenberg’s parents were live-in caregivers for several ill women of The Body. Her mother did not like the close proximity to the women, but Rodenberg was ecstatic to return to a sense of normalcy — a life that came with public school and a slackening of the strict rules that governed communal life on the farm. After Duluth, the family job-hopped until they found themselves back in Seco, Kentucky, building a house on a hill right below the home of Rodenberg’s grandparents, who were excited for their return.

Though her youth came with many hardships and many individuals she could blame, Rodenberg maintains a voice of acceptance and understanding, realizing that people are shaped and determined by their circumstances. As she writes in the acknowledgments to the book:

My heart’s deepest desire is that Kin will open the floodgates for dozens, even hundreds of memoirs from rural-born women who have spent years of their lives in churches and kitchens, who daily rise to the impossible task of negotiating their identity, power, and freedom. I pray for an embarrassment of these riches, a deafening chorus of gorgeous, complicated voices, loud enough to drown out the stereotypes and shame that have haunted our lives.

In her determination to tell not just her own story, but the entire history of a family, Rodenberg accomplishes what few memoirists have, painting a comprehensive and honest picture of women’s lives in rural Appalachia.

Abby N. Lewis is a part-time desk assistant for the North Knoxville Library and an adjunct English instructor at ETSU. She is the author of the poetry collection Reticent and the chapbook This Fluid Journey.