A Bottomless Well of Inspiration

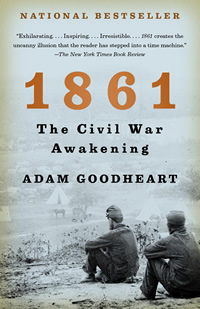

Historian Adam Goodheart explains why the Civil War is like both The Iliad and the Bible

In his book 1861: The Civil War Awakening, historian and journalist Adam Goodheart presents what he calls a “pointillist” picture of a country on the brink of self-destruction. Through a series of profiles and stories, Goodheart demonstrates how America was both gearing up for an epic conflict and coming to grips with the horror that lay before it—and all the while slowly realizing that whatever happened, it would change the nation forever. He spoke with Chapter 16 by phone prior to his forthcoming appearance at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville.

Chapter 16: Once you decided to write about the Civil War, how did you settle on the idea of writing about a particular year—and why 1861?

Adam Goodheart: The genesis of the book was in a bundle of letters that I found in the attic of an old plantation house here on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where I live. The letters documented the dilemmas faced by a man who was serving as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1861, as the country was falling apart. He was stationed out in Indian Territory, in what is now Oklahoma, and he was trying to decide what to do as the country went to pieces. Should he stay loyal to the country whose flag he had fought under for decades, or should he stay loyal to the South, since he considered himself a Southerner, being from Maryland? Those letters brought me into that moment and into the dilemma that man faced, and I decided I wanted to tell a story of a big moment in history through a series of small, individual stories.

Chapter 16: That’s what is so moving about the book. The Civil War is often framed as either inevitable or the result of political mistakes, in either case without any connection to the lives of everyday people. Your book does a great job bringing that story to life.

Goodheart: All of us know from our own times that history isn’t something that happens because of one speech that’s made or one law that’s passed, but that it’s an accumulation of individual moments and individual decisions and individual dilemmas for millions of people. That’s what I try to capture in the book—a pointillist image of that moment, that crisis. Wars, civil wars especially, have a gravitational pull of their own, drawing in many people for many reasons. All too often the depictions of war in either popular history or academia have been much too reductive. I wanted to recapture some of the complexity of actual human experience.

Chapter 16: How did you find the stories you wanted to tell?

Chapter 16: How did you find the stories you wanted to tell?

Goodheart: My background is one that combines academia with journalism. When I was a full-time journalist, I would be assigned by an editor to go to a foreign country and send back a magazine piece about it. That’s how I treat history: it’s often been said that the past is a foreign country, and I try to be a foreign correspondent in the land of the past. When I was a journalist overseas, I would need to identify the twelve people I had to meet and the six spots I really had to visit, and then distill those experiences into a story that captured the place for my readers. That’s what I tried to do with 1861. I visited a moment in time and looked for people and stories that would bring that moment to life for readers.

Chapter 16: One story that grabs me, and probably grabs most readers, is that of Elmer Ellsworth. His story seems to capture the nut of what you’re trying to say with the whole book. Who was he?

Goodheart: Ellsworth is one of my favorite characters in the book, and even though his story comes in the middle, it is what I started writing first and what really pulled me into that moment in time. He was a young man who became first a pop-culture hero and then a martyr of war and a national icon. He sparked a cultural craze in late 1850s, what began as cultural phenomenon and then became a military one, known as the Zouaves. Zouaves were troops of a kind that originated in Europe, known for uniforming themselves in Moroccan-style fezzes and baggy pants. They would take the battlefield this way and perform military drills that were a cross between Cirque du Soleil and Seal Team 6. They’d turn summersaults and twirl bayonets and perform acrobatics. Elmer Ellsworth became obsessed with the Zouaves and created a group of Zouave cadets that toured America to great acclaim in the late 1850s. He became almost a nineteenth-century rock star.

When the Civil War began he formed a regiment of Zouaves made up of New York City firemen. He led these troops as part of the first wave of Union troops into Virginia during the first weeks of war. That came about partly because he had become good friends with Abraham Lincoln, had been practically adopted as a member of the Lincoln family. His death in the very first weeks of the Civil war—a death that occurred not in the glory of the battlefield but in a squalid double murder on the staircase of a cheap hotel—was a signal moment in the war.

Chapter 16: You’ve said before that there are a lot of things that historians can learn from novelists. Like what?

Chapter 16: You’ve said before that there are a lot of things that historians can learn from novelists. Like what?

Goodheart: So many history books present almost mechanical versions of the past. Certain popular historians can take an event like the Civil War and reduce it to lines and arrows on a battlefield. Whose troops are charging against whose. There’s another type of history, usually written by academics, that reduces the past to pie charts and bar graphs, that takes a complicated moment in time and assigns different behaviors to different economic and ethnic classes of people. But we all know that’s not the way that the world works. We all know that life is made up of many different, interwoven, and often contradictory hopes, fears and ambitions. I think novelists often do a better job of capturing that complexity than historians do. But that’s something I try to do in the history I write. Instead of trying to reduce an event as big as Civil War to a single argument, I’d like to think the complexity of the different stories I tell is its own argument. I try to bring readers into a historical moment not just in an intellectual way but in an experiential way.

Chapter 16: But there are pitfalls in relying too much on the novelist’s toolbox, right?

Goodheart: I do keep my work grounded in the important academic work that’s been done, especially in the past few decades, on the Civil War. One shouldn’t let oneself become too seduced by a single story into thinking that it stands for a universal experience.

Chapter 16: That said, it feels like such a natural way to approach the history of the era. The Civil War is, after all, our Iliad, the font of a thousand American stories.

Goodheart: There have been, they say, more than 75,000 books published about the Civil War, more than one per day since the surrender at Appomattox, which is a lot of books. But I think it is one of those epics like The Iliad, like the Bible stories, that can be told and retold by each generation. When people ask me, ‘Why do you study the Civil War?’ of course one can say all sorts of things about its relationship to the nation we have become, to the continuing dilemma of race in this country. But I also need to talk about how marvelous the characters and episodes are and the way they’ve continued to inspire generation after generation of American artists and writers.

One of the examples I love the most is a story Bob Dylan recounts in the first volume of his memoirs, when he describes arriving in New York as a very young man fifty years ago, during the hundredth anniversary of the Civil War. Dylan would go at least once a week to the New York Public Library and scroll through the microfilmed newspapers and see what was happening exactly that week one hundred years before. He said he was obsessed with speeches and sermons and the ‘epic bearded characters,’ as he called them, who were on stage at that moment in American history. As he describes it, it was the Civil War era that inspired much of his music and poetry. So I think it’s a nearly bottomless well, not just for historians but for writers of all kinds.

Clay Risen is a regular Chapter 16 contributor and the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination. Adam Goodheart will discuss 1861: The Civil War Awakening at the twenty-fourth annual Southern Festival of Books, held October 12-14 at Legislative Plaza in Nashville. All events are free and open to the public.