A Country of Purity

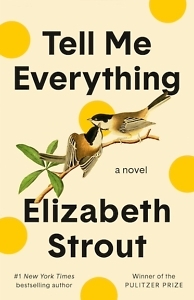

With Tell Me Everything, Elizabeth Strout unites her most beloved characters

Over the last two decades, Elizabeth Strout has quietly joined an increasingly exclusive club: literary writers whose work is both critically lauded and enormously popular. Her achievement is all the more remarkable for the fact that her most popular novels and story collections are all set in small, remote New England towns and follow the lives of quiet, taciturn, outwardly unremarkable people.

Since the publication of My Name is Lucy Barton, the titular Lucy has returned in three subsequent volumes, becoming, in effect, Strout’s alter ego: an acclaimed fiction writer who splits time between New York and small-town Maine, and whose work examines the interior lives and struggles of externally common, unremarkable people. Strout’s most famous creation is the curmudgeonly Olive Kitteridge, title character of the story collection which won the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted into an Emmy Award-winning limited series starring Frances McDormand as Olive. Between Olive Kitteridge and My Name is Lucy Barton, Strout delivered a bit of an outlier in her oeuvre: The Burgess Boys, a novel about two brothers who left Maine to become attorneys in New York but are called back home to aid their sister when her troubled teenaged son is charged with a hate crime.

Given the attachment readers have formed to Strout’s characters — chiefly Lucy Barton, but also Bob Burgess, the younger, more endearing of the Burgess brothers, and even the comically cranky, mercilessly blunt but nevertheless endearing Olive Kitteridge — Strout’s choice to bring them all together feels both thematically appropriate and like a gesture of generosity to the many readers who have embraced her work. Tell Me Everything returns to Crosby, Maine, and the neighboring environs, where Lucy Barton continues to live part-time with her ex-husband after sheltering there together during the Covid-19 pandemic (the subject of 2021’s Oh William!). Bob Burgess now lives there as well, with his second wife Margaret, a Unitarian minister. Bob and Lucy have formed a fast friendship which takes on a “will they or won’t they” character as the novel progresses. A mutual friend connects Lucy with Olive Kitteridge, who has a story to tell to the famous writer “from away,” as outsiders are known to native Mainers. One story leads to another, and before long, Lucy and Olive are regularly meeting to trade stories.

The spine of the novel is a missing person-turned-murder mystery involving a middle-aged loner named Matthew Beach, whose mother’s body has been found in a quarry. Given the isolated nature of his and his mother’s existence and his reputation as an oddball, Matthew naturally becomes the prime suspect in the murder. The steady, big-hearted Bob Burgess takes the case and becomes a mentor to Matthew, who, in addition to appearing somewhat hapless and unstable, does not appear to be telling Bob everything he knows about the circumstances around his mother’s disappearance and death. The case develops slowly. Tell Me Everything is not a murder mystery novel; it’s an examination of the mysteries of human character and experience. Near the novel’s conclusion, in characteristically blunt fashion, Olive Kitteridge asks Lucy to explain the point of her stories: “’People,’ Lucy said, quietly leaning back. ‘People and the lives they lead. That’s the point.’” Olive’s reply? “Exactly.”

The spine of the novel is a missing person-turned-murder mystery involving a middle-aged loner named Matthew Beach, whose mother’s body has been found in a quarry. Given the isolated nature of his and his mother’s existence and his reputation as an oddball, Matthew naturally becomes the prime suspect in the murder. The steady, big-hearted Bob Burgess takes the case and becomes a mentor to Matthew, who, in addition to appearing somewhat hapless and unstable, does not appear to be telling Bob everything he knows about the circumstances around his mother’s disappearance and death. The case develops slowly. Tell Me Everything is not a murder mystery novel; it’s an examination of the mysteries of human character and experience. Near the novel’s conclusion, in characteristically blunt fashion, Olive Kitteridge asks Lucy to explain the point of her stories: “’People,’ Lucy said, quietly leaning back. ‘People and the lives they lead. That’s the point.’” Olive’s reply? “Exactly.”

There’s a kind of alchemy at work in Elizabeth Strout’s prose style. Her sentences are straightforward, unadorned, even folksy, thanks to Strout’s pitch-perfect rendering of the small-town New England dialect. The characters and circumstances summon memories of novels set in places with names like Lake Wobegon or Mitford, stories populated with regular folks who go to church and tend to their sick friends and relatives and fill their days with the kind of communal activities small-town people used to do before smartphones and streaming media. (With the exception of one specific plot element relating to the murder case, there’s a blessed absence of technology in the lives of these aging Boomers.)

But despite the Norman Rockwell quality of the setting, Strout is no sentimentalist. The lives of her people are defined by the ways they have been broken — by betrayal, abuse, death, or just the unavoidable hardness of the world — and the ways they depend on each other to move forward. Her sentences resonate with subtle yearning, reminding us, as Sherwood Anderson did long ago, that the interior lives of all people, however seemingly common or misshapen, are pregnant with conflict, tragedy, and above all, meaning. “What does anyone’s life mean?” Lucy Barton asks. Lucy is always searching. She seems to find the closest thing to an answer she’s likely to get in the act of storytelling. Talking, writing, listening, caring — this, Elizabeth Strout teaches us, is where we find meaning.

“People suffer,” says Olive Kitteridge. “They live, they have hope, they even have love, and they still suffer. Everyone does.” With astonishing grace, wit, compassion, and honesty, Elizabeth Strout reminds us how we persist in spite of the certainty of suffering: by telling our stories, and, of course, through love. “Love comes in so many forms,” says Lucy Barton, “but it is always love.”

Ed Tarkington is the author of two novels, Only Love Can Break Your Heart (2016) and The Fortunate Ones (2020). He lives in Nashville.