A Dazzling Writer of Flawed People

Lorrie Moore’s work strikes a chord

In a 2024 Q&A with The Guardian, Lorrie Moore makes two bold claims, the first regarding her appreciation for Miranda July’s All Fours: “Well, that’s what fiction is for — flawed but interesting women.” She goes on to assert: “I would never read literature for comfort. I would read literature for transport and for meeting a few people I would never want to meet in real life.”

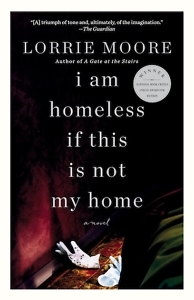

Moore, the 2025 guest author in Chattanooga State’s Writers@Work program, has the bona fides to make such claims. Her work has been celebrated since her 1985 debut, the short story collection Self-Help, which — not coincidentally — features plenty of flawed but interesting women. Her 1994 novel, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?, had Nick Hornby naming her “the best American writer of her generation,” and her latest, I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home, won the National Book Critics Circle Award. In all her writing, readers will find characters they might never want to meet in real life.

Take, for example, Noel from the story “Real Estate,” collected in Birds of America. The story’s protagonist is Ruth, a woman who has survived both cancer and her husband’s many affairs with a brash and bitter laughter (more than two pages filled with just the word “Ha!”) and a certain resignation: “Marriage, she felt, was a fine arrangement generally, except that one never got it generally. One got it very, very specifically.” Noel is the lawn guy Ruth phones about the crows in their pear tree. He is also the guy who accidentally flicks a rubber band at his girlfriend’s chin during an argument, the guy who starts breaking into houses and robbing people at gunpoint and forcing them to sing because he is also a guy who somehow doesn’t know any songs.

Noel’s lack of music is perhaps more offensive to Moore than the armed robbery because, to her, music is central to the human experience. In Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?, Berie and Sils are always strumming guitars, listening to records, creating harmonies in the back of a cab. Like Berie, Moore grew up making music; she has even claimed that failing to make the St. Lawrence College choir in freshman year is what pointed her to writing. Perhaps she had a transcendent moment like the 10th-grade choir rehearsal Berie describes:

Noel’s lack of music is perhaps more offensive to Moore than the armed robbery because, to her, music is central to the human experience. In Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?, Berie and Sils are always strumming guitars, listening to records, creating harmonies in the back of a cab. Like Berie, Moore grew up making music; she has even claimed that failing to make the St. Lawrence College choir in freshman year is what pointed her to writing. Perhaps she had a transcendent moment like the 10th-grade choir rehearsal Berie describes:

[T]his singing, this light, this was girls, after weeks of rehearsal, celebrating the ethereal work of their voices, the bell-like, birdlike, child-sound they could still make so strongly in unison. Strung along the same wire of song, we lost ourselves; out of separate rose and lavender mouths we formed a single living thing, like a hyacinth. It seemed even then a valedictory chorus to our childhood and struck us deep in the brain and low in the spine, like a call, and in its wave and swell lifted us, I swear, to the ceiling in astonishment and bliss, we sounded that beautiful. All of us could hear it, aloft in the midst of it, no boys, no parents in the room, no one else to tell us, though we never managed to sound that beautiful again.

Or the moment adult Berie joined “an entire roomful of women” in a Joni Mitchell song at a cocktail party:

They quit conversations, touched people’s arms, turned toward the corner stereo speakers and sang in a show of memory and surprise. All the women knew the words, every last one of them, and it shocked the men.

Much of Moore’s work lives in this idea — of flawed but interesting women knowing things that are foreign to the men around them. In selecting her “You’re Ugly, Too” for The Best American Short Stories of the Century, editor John Updike claims it expresses “the smoldering rage of the radically discontented female,” a phrasing that says more about the turn-of-the-millennium world (and Updike’s place in it) than it does about her work. He doesn’t acknowledge — as countless writers will — her virtuosic, headlong prose, what Dan Kois in The New York Times Magazine called “elevated, often dazzling language to evoke a complex emotional state” or what Lauren Groff, writing in The New York Review, described as “her astonishing facility with metaphor.” Updike doesn’t note the control and precision she exercises or the clever wordplay; he doesn’t seem to know the words to her song. But so many others do. Moore is a writer’s writer, especially for women, like Groff, who didn’t see themselves in the canon but heard in Moore “a voice that could be your own.”

Much of Moore’s work lives in this idea — of flawed but interesting women knowing things that are foreign to the men around them. In selecting her “You’re Ugly, Too” for The Best American Short Stories of the Century, editor John Updike claims it expresses “the smoldering rage of the radically discontented female,” a phrasing that says more about the turn-of-the-millennium world (and Updike’s place in it) than it does about her work. He doesn’t acknowledge — as countless writers will — her virtuosic, headlong prose, what Dan Kois in The New York Times Magazine called “elevated, often dazzling language to evoke a complex emotional state” or what Lauren Groff, writing in The New York Review, described as “her astonishing facility with metaphor.” Updike doesn’t note the control and precision she exercises or the clever wordplay; he doesn’t seem to know the words to her song. But so many others do. Moore is a writer’s writer, especially for women, like Groff, who didn’t see themselves in the canon but heard in Moore “a voice that could be your own.”

When Noel breaks into Ruth’s house, the song she sings (at gunpoint) is “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” He is so taken with it that he pauses to write down the words, and “with the beginning of the tune edging into his head — pardon me, boys — something exploded in the room.” That something was a gun, held by Ruth, shooting him dead. Her husband irrationally asks, “Did you have to be such a good shot?” to which she replies, “I’ve been practicing.” Like Ruth, I know all the words to the “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” Like Berie, I know the transcendent feeling of voices lifted together, the harmonies swelling to fill your whole body. And like Lorrie Moore, I know the power of metaphor. Pardon me, boys.

Sara Beth West is a librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Kirkus, Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.