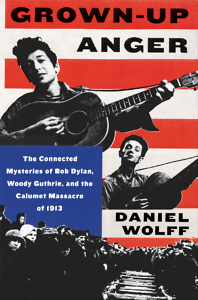

A Kind of Rage

Daniel Wolff’s Grown-Up Anger examines the social impact of American folk music

“I was thirteen and angry,” writes Daniel Wolff at the outset of Grown-Up Anger. He’s explaining what first drew him to the music of Bob Dylan-and from Dylan to Woody Guthrie, and from Guthrie to the tumultuous history of the organized-labor movement. The tragic consequences of attempts to suppress labor unions were best symbolized for Guthrie and Dylan, and eventually for Wolff himself, by the Italian Hall Disaster of 1913.

At a Christmas party for striking union members and their families in Calumet, Michigan, seventy-four people-many of them children-lost their lives when someone called out, “Fire!” and nearly 400 party-goers stampeded down a single narrow stairwell from the second floor. They were fleeing a fire that did not exist. Though the culprit remains unknown, most believed he was an anti-union activist.

At a Christmas party for striking union members and their families in Calumet, Michigan, seventy-four people-many of them children-lost their lives when someone called out, “Fire!” and nearly 400 party-goers stampeded down a single narrow stairwell from the second floor. They were fleeing a fire that did not exist. Though the culprit remains unknown, most believed he was an anti-union activist.

The most prominent proponent of this theory was Woody Guthrie, who memorialized the tragedy in song. “1913 Massacre” is a narrative about the powerful and greedy who mercilessly crush efforts by laborers to organize in pursuit of safe working conditions and a living wage. Years later, Bob Dylan paid homage to his hero and made his allegiances plain by borrowing the melody of “1913 Massacre” for “Song to Woody,” his tribute to Guthrie. “Here’s to the hearts and the hands of the men,” Dylan sings, “That come with the dust and are gone with the wind.”

Wolff’s own introduction to this story begins, fittingly enough, with rock ‘n’ roll, specifically with 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” The song was released at a time when President Lyndon Johnson was building up troops in Vietnam and the hope inspired by the March on Washington had yielded to fear and anger following the assassination of Malcolm X and the Watts Riots. The youth of America were growing increasingly restless, turning away from traditional role models toward the new sound coming out of their radios and the defiant voices of the people creating it-and in particular the voice of Bob Dylan.

For Wolff, “Like a Rolling Stone” didn’t directly address the unrest in the world around him. Instead, it brought forth a “corrosive, uncompromising sound” which “proclaimed, maybe confirmed, that the country was going through its own adolescence-confused, trying to figure out what it wanted to be when it grew up.” That sound led him to Dylan’s early career as a folk singer and on into Woody Guthrie’s voice of social activism. (“This Machine Kills Fascists” was emblazoned on Guthrie’s guitar.) Through Guthrie and the connection between “Song to Woody” and “1913 Massacre,” Wolff takes a deep dive into the plight of the American underclass in the early years of the twentieth century and the subsequent struggles to unionize the workforce.

For Wolff, “Like a Rolling Stone” didn’t directly address the unrest in the world around him. Instead, it brought forth a “corrosive, uncompromising sound” which “proclaimed, maybe confirmed, that the country was going through its own adolescence-confused, trying to figure out what it wanted to be when it grew up.” That sound led him to Dylan’s early career as a folk singer and on into Woody Guthrie’s voice of social activism. (“This Machine Kills Fascists” was emblazoned on Guthrie’s guitar.) Through Guthrie and the connection between “Song to Woody” and “1913 Massacre,” Wolff takes a deep dive into the plight of the American underclass in the early years of the twentieth century and the subsequent struggles to unionize the workforce.

In doing so, he makes a persuasive case for the relevance of popular music in truth-telling, rallying activism, and opening the minds of young people to the possibility that the world can and should be changed. “Never forget how adults dismiss what kids say, assume they’re wrong, treat them like something that isn’t finished,” Wolff writes. Considering our current historical moment, in which the students of Parkland High School are met with similar words from far too many so-called grown-ups with guns, Wolff’s words feel particularly timely.

And not just in matters of gun control:

Between 2009, when the Great Recession officially ended, and 2013, America’s wealthiest 1 percent accounted for 95 percent of the total growth in income. Meanwhile, average family income for 90 percent of American families dropped by more than 10 percent. Four years after the housing bubble burst, there were five and a half million fewer full-time jobs. … The year Dylan cut ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ a typical male worker’s income was about $34,000. Almost five decades later, the comparative figure was $33,000. … Take out government jobs and look only at the private sector, and fewer than 7 percent of employees belonged to a union: the lowest level in a century. The lowest level, that is, since 1913.

This analysis highlights the startlingly cyclical nature of history and the peril of our blindness to the lessons of the past. We cast about for easy solutions when the only answer has been right in front of us for as long as songs have been sung. “See what your greed for money has done,” sang Woody Guthrie in “1913 Massacre.” “I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it,” sang Bob Dylan. “A hard rain’s a-gonna fall.”

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.