A Master of Fact

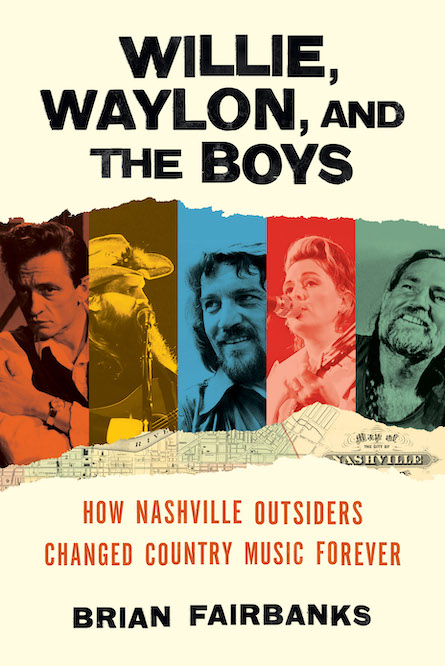

Legendary nonfiction writer John McPhee heads to Tennessee to accept the Nashville Public Library Literary Award

My job is to teach college journalism students the art of nonfiction, and at some point during every semester, I invariably tell them that if they really want to write well, they should try to be more like John McPhee. For forty-six years, McPhee has produced quietly brilliant work for The New Yorker and (very rarely) other magazines—long reported pieces that often wind up as books. McPhee defies easy categorization: he investigates subjects as varied as sports (basketball, tennis, golf, lacrosse), geology (hard rock, tectonic, volcanic, sedimentary), canoes, roadkill, oranges, and fish, to name a few. He writes always in the first person but he does not make himself a principal character in whatever story he sets out to tell. McPhee developed this style during the rise of New Journalism, but his work features neither the manic experimentation of Tom Wolfe nor the narcissistic indulgence of Hunter S. Thompson. He simply writes beautiful sentences about interesting things and people. This weekend, the Nashville Public Library will honor his body of work by giving McPhee the eighth annual Nashville Public Library Literary Award.

Since 1975, McPhee has also been a teacher of writing at Princeton, and his tips are routinely repeated in journalism schools across the country: ask the same question in slightly different ways until your exasperated interview subject concludes you are an idiot, and answers in simple, vivid quotes that any idiot can understand; read as many books on your topic as you can find, no matter how obscure; place scenes and characters and interesting facts on note cards, and shuffle their order continuously in search of the perfect story structure; keep a couch in your office, so that if you are ever stuck while writing, you can take a short nap and wake inspired. Even when I was in graduate school and teaching for the first time, I knew I was not unique in recommending McPhee as a model. By then, an entire generation of writing teachers—including some, like Tracy Kidder, who were once McPhee’s own students—had been offering up his work as the best possible example of the art of nonfiction.

Just consider McPhee’s description of Fred Brown, a resident of Hog Wallow, a hamlet (although McPhee himself would never stoop to such a pun) of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens:

Just consider McPhee’s description of Fred Brown, a resident of Hog Wallow, a hamlet (although McPhee himself would never stoop to such a pun) of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens:

I walked through a vestibule that had a dirt floor, stepped up into a kitchen, and went into another room that had several overstuffed chairs in it and a porcelain-topped table, where Fred Brown was seated, eating a pork chop. He was dressed in a white sleeveless shirt, ankle-top shoes, and undershorts. He gave me a cheerful greeting and, without asking why I had come or what I wanted, picked up a pair of khaki trousers that had been tossed onto one of the overstuffed chairs and asked me to sit down. He set the trousers on another chair, and he apologized for being in the middle of his breakfast, explaining that he seldom drank much but the night before he had had a few drinks and this had caused his day to start slowly. “I don’t know what’s the matter with me, but there’s got to be something the matter with me, because drink don’t agree with me anymore,” he said. He had a raw onion in one hand, and while he talked he shaved slices from the onion and ate them between bites of the chop.

Over the course of several pages, the reader comes know Fred Brown and his cluttered house in the Pine Barrens as fully as any of the Alabama sharecroppers and their cabins depicted in James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, but with more surprising and often gently humorous observations. Through Fred Brown, the reader also begins to know something about the region, and to care about it as deeply as Brown does. This is McPhee’s genius: he writes about interesting characters in such a way that readers don’t even notice they’re also absorbing facts.

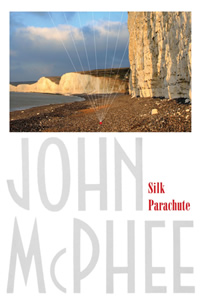

Since 1965, when he became a staff writer for The New Yorker, McPhee has published, on average, a book every eighteen months; he is now up to twenty-eight. In Silk Parachute, published last year and now out in paperback, the eighty-year-old author seems, in his usual quiet and self-deprecating way, to have noticed the fact of his age. In any case, he reveals more of himself in this essay collection than he ever has before. The title comes from a very short preface about McPhee’s own childhood, his mother, and a favored toy: a black rubber ball, bought at LaGuardia airport in the 1930s, containing a silk parachute. “If you threw it high into the air, the string unwound and the parachute blossomed,” McPhee explains. “If you sent it up with a tennis racquet, you could put it into the clouds. Not until the development of the multi-megabyte hard disk would the world ever know such a fabulous toy.”

Over the course of the eight fairly recent articles that make up the collection, McPhee investigates the usual eclectic mix of topics: English chalk, lacrosse, large-format photography, and so on. But for the first time the characters through which he introduces these topics are McPhee himself, members of his immediately family, and a couple of longtime personal friends. Progressing through the book, you realize that McPhee is finally sharing his own life, the life of a man whose marvelous talent has always been his fabulous toy. “Folded just so, the parachute never failed,” he writes in the preface.” Always, it floated back to you—silkily, beautifully—to start over and float back again. Even if you abused it, whacked it really hard—gracefully, lightly, it floated back to you.”

Over the course of the eight fairly recent articles that make up the collection, McPhee investigates the usual eclectic mix of topics: English chalk, lacrosse, large-format photography, and so on. But for the first time the characters through which he introduces these topics are McPhee himself, members of his immediately family, and a couple of longtime personal friends. Progressing through the book, you realize that McPhee is finally sharing his own life, the life of a man whose marvelous talent has always been his fabulous toy. “Folded just so, the parachute never failed,” he writes in the preface.” Always, it floated back to you—silkily, beautifully—to start over and float back again. Even if you abused it, whacked it really hard—gracefully, lightly, it floated back to you.”

Appropriately, the short essay that serves as the book’s afterword explains McPhee’s reasons for choosing to live his entire life in Princeton, New Jersey. Gracefully, lightly, and not at all accidentally, he ends with the profile character whom journalism teachers so often point to as a writing model:

I remember Fred Brown, who lived in the Pine Barrens of the New Jersey Coastal Plains, remarking years ago outside his shanty: “I never been nowhere where I liked it better than I do here. I like to walk where you can walk on level ground. Outside here, if I stand still, fifteen or twenty quail, couple of coveys, will come and go around. The gray fox don’t come nearer than the swamp there, but I’ve had coons come in here; the deer will come up. Muskrats breed right here, and otters sometimes. … I never been nowhere I liked better than here.”

There is no place I would rather be than with a new McPhee book in hand. And after each, I treasure the hope that there will be more to come, just as I look forward to that day each semester when I try to explain the art of narrative description to my students, and once again Fred Brown floats back to me.

John McPhee will give a free public reading at the Nashville Public Library on November 12 at 10 a.m.