Loving Country

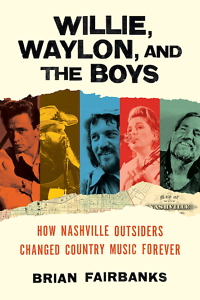

Willie, Waylon, and the Boys tells the stories of Nashville’s quintessential outsiders

The music scene in Nashville is tricky and hard to describe until you figure out how obsessed the city is with the relationship between conformity and rebellion. Brian Fairbanks provides plenty of detail about the full-cylinder lives of country music iconoclasts Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, and Waylon Jennings in Willie, Waylon, and the Boys: How Nashville Outsiders Changed Country Music Forever.

Like rock stars of comparable stature — Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis — Fairbanks’ outsiders were egotists and rule-breakers whose bad behavior fueled some of their best art. More often than not, one or more of these outlaws wound up in a crumpled car next to a telephone pole or in a Texas jail, chasing endless kicks that included sex, drugs, and country music.

The expansiveness in the lives of Cash, Nelson, Kristofferson, and Jennings went along with a rebellious streak that Fairbanks situates in the world of rock ‘n’ roll. Willie, Waylon, and the Boys opens in February 1959, when Jennings was on tour as the bass player with the rock ‘n’ roll star Buddy Holly in Iowa. Jennings and Holly had connected after Jennings, who was a disc jockey on Lubbock, Texas, radio station KLLL, began playing Holly’s records. Holly was ambitious to become a producer, and he recorded the young Jennings with the great R&B saxophonist King Curtis on a September 1958 version of the Cajun standard “Jole Blon.”

After Holly’s death on Feb. 3, 1959, in an airplane crash that has been mythologized in pop history through Don McLean’s 1971 song “American Pie,” Jennings regrouped. He had given up his seat on the small aircraft at the last minute. Jennings’ subsequent music contained elements of Holly’s gentle rock ‘n’ roll and hints of the darker moods of rockabilly, a music that Cash had influenced through his 1950s work with Memphis producer Sam Phillips at Sun Records.

Meanwhile, Nelson became an all-purpose interpreter who sounded as natural singing Hoagy Carmichael songs as he did rearranging “Whiskey River,” a tune by fellow Texas singer Johnny Bush that Nelson played in a style that recalled the approach of The Allman Brothers Band. Of the four singers—they would form a country super-group, The Highwaymen, in the early 1980s — Kristofferson was most affected by the pressures of stardom. After Janis Joplin recorded his “Me and Bobby McGee” in 1970, Kristofferson’s music career gave way to acting.

It’s arguable that Kristofferson — never a gifted singer — came across better in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore than he did in his rather prolix mid-‘70s work. By the time he released his album Spooky Lady’s Sideshow in 1974, Kristofferson had enough celebrity clout to collaborate with Byrds singer Roger McGuinn, Bob Dylan associate Bob Neuwirth, and actor Seymour Cassell on a downbeat song called “Rescue Mission.”

It’s arguable that Kristofferson — never a gifted singer — came across better in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore than he did in his rather prolix mid-‘70s work. By the time he released his album Spooky Lady’s Sideshow in 1974, Kristofferson had enough celebrity clout to collaborate with Byrds singer Roger McGuinn, Bob Dylan associate Bob Neuwirth, and actor Seymour Cassell on a downbeat song called “Rescue Mission.”

Fairbanks quotes the Oklahoma-born musician John Buck Wilkin — a longtime friend of Kristofferson’s who had recorded a chart-topping Beach Boys-style rock tune, “G.T.O.,” in 1964 in Nashville with a group of session musicians — on the effects of celebrity on Kristofferson’s art:

“It got to the point where he got to town to do a concert and if you could get on the bus, you were cool,” says Nashville friend Bucky Wilkin. “He neglected his writing career, and became this sort of Burt Reynolds character, where people knew him and he was pretty successful, but that magic had gone from his writing … but maybe he’d done enough.”

Wilkin, who died near Linden, Tennessee, on April 6, 2024, was speaking from the inside. Wilkin played guitar on many sessions and made a pair of experimental rock albums in the early 1970s that mark him as a great outlier in Nashville music. Like many obscure figures from that era, Wilkin had a career that deserves a place in the city’s musical history.

When the old guard of Nashville ran up against the wild eclecticism that Nelson perfected on mid-‘70s albums like Red Headed Stranger and The Sound in Your Mind, the outlaw movement began an ideological struggle that Fairbanks poses as a fundamental fact of being in Nashville. “There are two populations living on top of each other,” he writes, “with each claiming the real estate.”

Willie, Waylon, and the Boys tells the story of this ideological struggle, which you might describe as the fight between Americana, a form that signals authenticity at every turn, and mainstream country, a version of pop music that simulates authenticity. In the final section of the book, Fairbanks makes comparisons between the pioneering ‘70s outlaws and contemporary rebels like Sturgill Simpson, Lukas Nelson, Jason Isbell, and queer Americana star Melissa Carper. Country music ideologues continue to disagree about what the music means. It could be that loving country is about knowing exactly how much conformity you’re willing to take before you’ve had enough.

Edd Hurt is a writer and musician in Nashville. He’s written about music for Nashville Scene, American Songwriter, No Depression, The Village Voice, and other publications. He produced and played keyboards on The Contact Group’s 2021 album of 1970s covers, Varnished Suffrages.