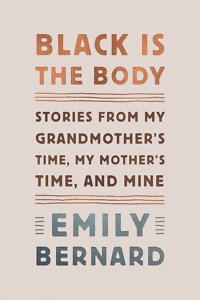

A Memoir in Mosaic

Emily Bernard’s new essay collection is set on the fault lines between north and south, black and white

There are stylistic echoes of Joan Didion—terse yet beautiful writing, a bracing honesty—in the graceful new essay collection by Emily Bernard, a Nashville native and the editor of Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, a New York Times Notable Book. Black Is the Body plumbs Bernard’s own psychic wounds, sifting nuggets of hope from the anguish of African-American history.

While Didion shifts between the poles of her imagination, Los Angeles and New York, Bernard sets her work on the fault lines between Burlington, Vermont, where she and her husband teach literature at the state university, and her childhood home, with forays into her family’s roots in rural Mississippi. West and East, North and South: our American mythology coiled within a compass. Didion’s essays are models of clinical observation, but Bernard leads us into her inner landscape with candor and confession. Beneath her still surfaces, a rage roils.

While Didion shifts between the poles of her imagination, Los Angeles and New York, Bernard sets her work on the fault lines between Burlington, Vermont, where she and her husband teach literature at the state university, and her childhood home, with forays into her family’s roots in rural Mississippi. West and East, North and South: our American mythology coiled within a compass. Didion’s essays are models of clinical observation, but Bernard leads us into her inner landscape with candor and confession. Beneath her still surfaces, a rage roils.

Black Is the Body pieces together episodes from across Bernard’s life, a kind of memoir-in-mosaic. The first chapter, “Scar Tissue,” is a gripping account of a crime spree in 1994, when she and six others were knifed by a deranged man at a coffee house in New Haven, Connecticut. The piece explores the violence wrought on black bodies, and in particular the bodies of black women, a prominent theme throughout this book.

The collection cuts back and forth in time: we see Bernard as a vulnerable graduate student, a bookish if smart-alecky adolescent, a professor coaxing her white students to speak the “N-word,” an archivist of family lore, a devoted wife and mother who nevertheless craves solitude, and a woman of color who circles inexorably back to racial difference, finding delight in it, but also disappointment and bewilderment.

The collection cuts back and forth in time: we see Bernard as a vulnerable graduate student, a bookish if smart-alecky adolescent, a professor coaxing her white students to speak the “N-word,” an archivist of family lore, a devoted wife and mother who nevertheless craves solitude, and a woman of color who circles inexorably back to racial difference, finding delight in it, but also disappointment and bewilderment.

This is an essayist who takes risks, casting real people as characters: her Italian-American husband (and English department colleague), her adopted Ethiopian daughters, her stern Trinidadian father, her warm-hearted, gossipy mother and grandmother. Small moments open onto piercing revelations about race. A white boy who insults her daughter on a school bus. The night her teenaged grandmother ran into a pitch-black cornfield to escape a truck of leering locals.

Black Is the Body often rises to a taut lyricism, rich in detail and feeling. In this scene from the brilliant essay “Interstate,” Bernard takes her future spouse to meet her grandmother at a barbecue in Mississippi. There’s a flat tire on the freeway north of Jackson, where John’s whiteness serves as a shield to any redneck harassment but doesn’t inspire anything like a feeling of safety:

Within minutes John is underneath the car while my parents and I stand in a grassy depression near him. I feel pride as I watch my fiancé’s strong, tan arms move in confident, rhythmic silence as he replaces the spent tire with a spare that is, distressingly, nearly flat itself . . . There we stand—my black family, as vulnerable as an open window on a hot summer day in the South. We are bound by history and helplessness.

In “White Friend” Bernard compares her relationships with other women in a way that calls to mind Claudia Rankine’s Citizen but in a softer register; Bernard is both irked and sympathetic to those struggling with white privilege: “I know where this is going, having been there before with other white friends, the ones who see racism everywhere, hiding like a burglar behind potted plants in restaurants when I’m just trying to eat lunch in peace.” The divide haunts her but she nevertheless seeks the possibility of reconciliation. It will demand sacrifices from her, as she knows: struggle is endemic, the threat from white men omnipresent, the crippling sense of doubt evergreen. And yet redemption beckons.

As is often the case with collections, Black Is the Body is uneven, with lesser pieces that don’t quite rise to the heights of “Interstates,” “Going Home,” or “White Friend.” Quibbles aside, though, Black Is the Body marks the début of an essayist in command of her gifts, a book that belongs beside the best of contemporary autobiography.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.