A Picture of Home, Bittersweet and Ephemeral

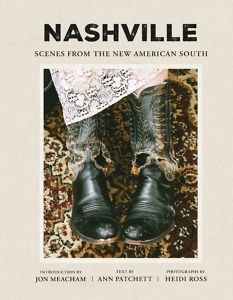

Photographer Heidi Ross and writer Ann Patchett capture the essence of the new Nashville—and the ghost of the old city, too

I began thinking about Nashville: Scenes from the New American South, the new book of photographs by Heidi Ross with text by Ann Patchett, while sitting at the window counter in Retrograde Coffee, a new place on Dickerson Pike. My view across the road revealed a weedy patch of pavement next to a faded sign, one of those big 1970s-era pieces, that identified the spot as a former used-car lot. On one side stood an old log cabin with a “No Trespassing” sign on its door. On the other side was a decrepit trailer. Behind them towered a newly constructed building, a noisy mix of angles and textures with windows that look a bit like they’d been pasted on at whim.

Inside Retrograde, meanwhile, there were brioche pastries and pour-over coffees. There were brushed-brass fixtures and reclaimed wood floors. Could I have chosen a more apt perch from which to page through Ross and Patchett’s new book, which also features a foreword by historian Jon Meacham? I could not. My Dickerson Pike panorama, I thought, could have been among Nashville’s pages.

At a time when “#NewNashville” has become a side-eye signal of disdain for the city’s convulsive growth, what can we make of these images of our city?

One thing, perhaps, is that the book seems both created from our present moment and stubbornly resistant to some of its recurrent themes. (Happy spoiler: there’s not a bachelorette in sight.) Paging through Nashville is a bit like opening one of those personalized books for kids. The story’s excitingly new, but look!—there’s a character named for you. It’s a kind of insider experience, terribly bittersweet because so much of it feels terribly ephemeral.

Which is to say, too, that the book is true to its namesake—a glorious blur of music and lights and smiles and signs and people always on the move. Here are images that could speak of no place else: Amanda Shires’s shoes backstage at the Ryman, country-music billboards, and so many murals—wings, bears, and Minnie Pearl, to name a few. Here are the Fisk Jubilee singers and Herb Williams’s crayons and Hillsboro High cheerleaders and children at play. Yet the book is equally fetching in its many quiet moments: a Ford Falcon, its orange paint peeling; a pair of fawns at Shelby Bottoms; gardening gloves hung out to dry.

If you’re a newcomer still buzzing on this town, you’ll find it irresistible. If you’re an old-timer, perhaps a bit wary of where the town is going, you’ll find it irresistible. If you’re a shop owner who sells beautiful, locally made things, you’ll be ordering copies. For who among us could resist opening this book—featuring Gillian Welch’s busted-up ostrich-skin boots, the lacey hem of her dress peeking out from the top edge of the frame—to see how our city might be reflected back to us?

Many of Ross’s photos seem unpremeditated, and that’s just the treatment the city needs now. This has always been a place for harsh stage lights and the perfect blowout, for production values that scream of big budgets and even bigger egos. But there’s something else here, too—a softness, a looseness, a willingness to while the day away on a bar patio or screen porch, to strum a few idle chords. This, too, is our city in its timelessness.

In the photo’s captions, Patchett’s trademark wit sings out. “Bobbie’s Dairy Dip has been in the same location since 1951,” she writes. “That’s also about how long people have been circling the block, looking for a parking place.” Here she is on David Rawlings: “He was trained at Boston’s Berklee College of Music. We don’t hold it against him.”

In the photo’s captions, Patchett’s trademark wit sings out. “Bobbie’s Dairy Dip has been in the same location since 1951,” she writes. “That’s also about how long people have been circling the block, looking for a parking place.” Here she is on David Rawlings: “He was trained at Boston’s Berklee College of Music. We don’t hold it against him.”

In an introductory essay, Patchett grapples with the central problem of talking about Nashville in 2018: it’s impossible, if you’ve been here any length of time, not to get snagged on talking about what Nashville was. And so she allows herself to do that, writing of the ferry that once crossed the Cumberland River and memories of Acme Feed & Seed, back when its purpose was to sell food for animals.

After all, Patchett writes, “When you look at anyone you’ve known for a long time, aren’t you seeing both the person they are now and the traces of all the people they used to be?” Still, it’s overwhelming, what’s happened here. Nashville has “gone from sleepy to vibrant in an anthropological blink of an eye,” she writes. “We’re not trying to immortalize it. We only mean to document the feeling of the place, to appreciate it and be grateful.”

And so, yes. Yes, from the vantage point of Dickerson Pike—or wherever in Nashville you might find yourself.

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch Writers’ Collective, a nonprofit literary center. She is the author of This Will Go Down On Your Permanent Record, a novel, and numerous journal and magazine articles.