A Solitary Being

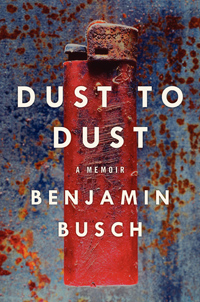

Benjamin Busch’s memoir, Dust to Dust, examines life through an elemental lens

”I knew very early that I was a solitary being.” Benjamin Busch begins his memoir, Dust to Dust, with that frank statement of self-sufficiency, and it serves as a road sign for the journey ahead. Readers in search of gossip, lurid accounts of dysfunctional family, or opportunities to be welcomed into the needy corners of the writer’s psyche won’t find any of those things in Dust to Dust. In a reversal of the usual memoirist’s strategy, Busch turns his attention away from matters of feeling and personal relationships in favor of an engagement with material existence. He delivers a series of meditations on elemental themes—“Water,” “Metal,” “Soil,” “Ash,” etc.—in which he embeds his memories in their physical context, inseparable from the eternal stuff of the world. The result is a slow and rambling book that is deliberately matter-of-fact about even the most dramatic events yet somehow manages to be engaging and, in the end, moving.

If Busch had chosen the ordinary options of chatty anecdotes or lyrical angst for his memoir, he would have had plenty of material to work with. He is the son of highly regarded novelist Frederick Busch (The Night Inspector, A Memory of War), and, now in his mid-forties, he has lived an unconventional, eventful life as an artist, soldier, and actor. He grew up in rural New York, where his father taught at Colgate University, and he spent part of his childhood with his parents in England. He studied art at Vassar and then joined the Marines, ultimately serving two tours of duty in Iraq. His foray into acting led to a recurring role on HBO’s The Wire. In 2006, his father died, struck down by a heart attack at the age of sixty-four. Less than a year later, his mother, Judith, died from a brain tumor.

If Busch had chosen the ordinary options of chatty anecdotes or lyrical angst for his memoir, he would have had plenty of material to work with. He is the son of highly regarded novelist Frederick Busch (The Night Inspector, A Memory of War), and, now in his mid-forties, he has lived an unconventional, eventful life as an artist, soldier, and actor. He grew up in rural New York, where his father taught at Colgate University, and he spent part of his childhood with his parents in England. He studied art at Vassar and then joined the Marines, ultimately serving two tours of duty in Iraq. His foray into acting led to a recurring role on HBO’s The Wire. In 2006, his father died, struck down by a heart attack at the age of sixty-four. Less than a year later, his mother, Judith, died from a brain tumor.

Busch reveals these broad facts of his bio over the course of the book, but he doesn’t build the narrative around them. They serve as backdrop while he focuses on particular, sometimes very small moments of his life under each elemental rubric. Dust to Dust begins with Busch’s childhood and ends with the deaths of his parents, but otherwise it honors no timeline, jumping across the years (and across continents) within each chapter. In “Water,” for example, Busch recalls his forbidden childhood play around a frozen river in New York, moves on to an account of Marine training maneuvers at the Black Sea, and then describes his harrowing role in settling a violent dispute over water rights in wartime Iraq—an occasion when, he writes, he thought it was “a perfect time to be killed.” He recounts numerous brushes with danger and death in this book, and his desire to transcend death by challenging it is tied up with his fascination with the material world. “I wanted to create something that could not be destroyed,” he writes in the prologue, “and to do that I had to disbelieve the evidence of destruction. I had to look at the bone and ash around me as the yield of errors, not of dreams.”

Busch ties his recollections together—gracefully, for the most part—through philosophical observations about the various elements, but those ruminations actually take up little of the book. He sticks mostly to the business of memory, employing a smooth prose style to convey dozens of small moments, some quite gruesome. In the chapter titled “Blood,” he walks through an Iraqi market: “There was a crooked gutter cut down the center of the meat market that oozed a puss of waste from slaughter, and the street was a blood-darkened orange that looked permanently wet. Wheeled carts of filthy chickens lined the passage and the shit-coated pens showed the success of recent sales with small pools of bright blood around them. Skinned goats hung from doorways.” The horrific scenes from Iraq are balanced by gentler passages from other eras of his life. His memories of his parents are often lovely and touching.

Busch ties his recollections together—gracefully, for the most part—through philosophical observations about the various elements, but those ruminations actually take up little of the book. He sticks mostly to the business of memory, employing a smooth prose style to convey dozens of small moments, some quite gruesome. In the chapter titled “Blood,” he walks through an Iraqi market: “There was a crooked gutter cut down the center of the meat market that oozed a puss of waste from slaughter, and the street was a blood-darkened orange that looked permanently wet. Wheeled carts of filthy chickens lined the passage and the shit-coated pens showed the success of recent sales with small pools of bright blood around them. Skinned goats hung from doorways.” The horrific scenes from Iraq are balanced by gentler passages from other eras of his life. His memories of his parents are often lovely and touching.

The tone of Dust to Dust is consistently restrained, even muted, whether Busch is describing a sprawl of daffodils or a mentally ill girl chained up in a courtyard in Iraq. Busch never points the reader to an emotion, and he rarely describes his own feelings in any depth. The book’s cold quality is heightened by the fact that the people in Busch’s life don’t get much attention. The only one who really comes across as a character is Frederick Busch, and that character is just a sketch of a personality: loving, anxious, and very smart, but without much depth or complexity.

Even so, Busch’s oddly affectless account of his life is quite effective in moving the reader, especially in the book’s final section, when Busch has to contend with relics and the actual remains of his parents. Through its meticulous cataloguing of one man’s confrontation with material existence, Dust to Dust conveys a struggle—and a mystery—we all share.

Benjamin Busch will discuss and sign Dust to Dust at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on June 24 at 3 p.m., and at Parnassus Books in Nashville on July 11 at 6:30 p.m.