A Southern Story

Andrew Ross reconstructs the history of one Shelby County plantation from multiple perspectives

The oldest home in Shelby County, Tennessee, can be found in the Memphis suburb of Bartlett. This two-story log house now serves as the museum at the heart of Davies Manor Historic Site, which teaches local history and provides outdoor recreation. In the 19th century, the cabin was surrounded by more than 1000 acres of plantation land, worked by African Americans in both slavery and freedom. The site remained a working farm through most of the 20th century, reaching approximately 2400 acres by the 1970s. In The Realms of Oblivion, due in June from Vanderbilt University Press, Andrew Ross excavates the stories of both the Davies family and the enslaved Blacks at Davies Manor, detailing a rich, complex history that penetrates through old myths.

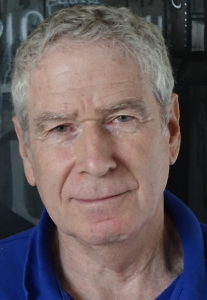

Ross is the museum director for The Blues Foundation in Memphis. He previously worked as the executive director for the Davies Manor Association, where he led the development of the award-winning exhibit Omitted in Mass: Rediscovering Lost Narratives of Enslavement, Migration, and Memory through the Davies Family’s Papers. He has an M.F.A. from the University of Memphis, and his writing has appeared in Memphis Magazine, Delta Magazine, Texas Highways, Mississippi Sports Magazine, The Daily Beast, and various newspapers. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Ross is the museum director for The Blues Foundation in Memphis. He previously worked as the executive director for the Davies Manor Association, where he led the development of the award-winning exhibit Omitted in Mass: Rediscovering Lost Narratives of Enslavement, Migration, and Memory through the Davies Family’s Papers. He has an M.F.A. from the University of Memphis, and his writing has appeared in Memphis Magazine, Delta Magazine, Texas Highways, Mississippi Sports Magazine, The Daily Beast, and various newspapers. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: There’s a modern character that looms over this history: Ellen Davies-Rodgers, the longtime Shelby County historian and founder of the Davies Manor Association. How did she shape an understanding of Davies Manor and the 19th century South?

Andrew Ross: To understand how Davies-Rodgers shaped local history in this corner of Tennessee, you really have to begin by understanding the political clout she wielded. Along with authoring books and her role as the county historian, she was active in many other spheres. But at her core she was a political powerbroker who knew how to get what she wanted, whether that had to do with educational issues, road projects, elections, or how history got told.

In the 1940s and 1950s, she was closely connected to the Edward Hull “Boss” Crump political machine. I personally believe that she modeled herself after Crump in certain respects. Fundamentally, though, she was someone who understood the intertwined relationship between political power and shaping historical memory. The agricultural estate that she inherited and owned from the 1930s to her death in 1994 functioned as both the literal and figurative foundation for her larger ambitions. She single-handedly created Davies Manor as a historic attraction that centered her estate. And the same thing goes for the nostalgia-laden narratives about her family and community that emerged as an extension of Davies Manor and gradually became entwined with the broader story of Shelby County itself.

Chapter 16: The Realms of Oblivion seeks to recover the lives and stories of the enslaved people on the Davies property. What are the challenges in doing this work? What can it reveal?

Ross: Just locating key sources presents plenty of practical challenges. As a starting point, quite a bit of primary material held at Davies Manor had to be transcribed and studied with fresh eyes. Once I discovered governmental records involving earlier generations of the Davies family in Virginia and Middle Tennessee (places where they had owned plantations prior to coming to Shelby County), more and more outside material had to be transcribed and cross-referenced. That’s very time-consuming work. And much of what I found turned out to be extraneous.

Ross: Just locating key sources presents plenty of practical challenges. As a starting point, quite a bit of primary material held at Davies Manor had to be transcribed and studied with fresh eyes. Once I discovered governmental records involving earlier generations of the Davies family in Virginia and Middle Tennessee (places where they had owned plantations prior to coming to Shelby County), more and more outside material had to be transcribed and cross-referenced. That’s very time-consuming work. And much of what I found turned out to be extraneous.

But then suddenly crucial information emerged. In this case, it happened in legal records that centered around disputes over enslaved people. So now there were a host of new paths to follow and new names of people to try and trace through time. I think anyone who does this sort of research in obscure county courthouse records will face the challenge of choosing the right threads to follow.

Ultimately, regardless of what turns up or doesn’t, the source material is going to be grossly distorted and incomplete. With extremely rare exceptions, you’re working with records written by white people who saw Black people only as property. A host of deeper challenges emerges with how to read between the lines of such a problematic record of the past and to conceptualize all that’s missing. That’s a process that can and should evolve over time and involve collaborations.

It’s also where historic sites have such important roles to play. It’s my hope the accounts of enslaved people in this book will be seen as starting points that can spur on new reimagining and discoveries by others.

Chapter 16: How did the Civil War transform the Davies plantation? What did it mean for the Davies family?

Ross: On one hand, the Civil War devastated the Davies family. One brother died in a Union prisoner of war camp. Another returned home with severe psychological problems. Close acquaintances were killed. The demise of slavery and the Confederate economy brought heavy financial losses.

On the other hand, the Davies were in better shape than others in their community. Their home survived without damage, and their plantation remained productive through the whole of the war. As late as January 1865, records show Logan Davies leasing out enslaved people for year-long contracts. Cotton grown at the estate continued to be sold in Memphis despite the challenges of doing so under federal occupation. And after the war’s end, the Davies quickly returned to profitable cotton production by immediately transitioning to a sharecropping system that exploited the labor of the same people they’d just enslaved.

In terms of Civil War memory, it’s also very clear that subsequent generations of the family, including Ellen Davies-Rodgers, were deeply guided by Lost Cause interpretations.

Chapter 16: What did emancipation look like for the Black people on the land? How did Black life at Davies change during Reconstruction and into the Jim Crow era?

Ross: For most of the Black people who remained on the Davies’ land after the Civil War, their day-to-day existence remained impoverished and bound to field labor under sharecropping contracts. The plantation ledger books from the late 1860s and 1870s are revealing on this front. In a few cases, however, families formerly enslaved by the Davies did become landowners who ran successful farms.

Nearby, the Gray’s Creek Baptist Church centered an important Black community that went back to the 1840s. Closer to Davies, the Morning Grove Church became an important institution by the 1880s. So vital Black communities in the area did thrive in the wake of emancipation. But the white backlash to Reconstruction was very real. The Davies family was actively involved in local Democratic politics and efforts to reverse Black political advancements. As the book details, some of the worst instances of racial violence in late 19th-century Shelby County happened in areas immediately surrounding the Davies estate. So those traumas would have certainly impacted the Black community working and living there.

Chapter 16: Throughout your book, the theme of paradox keeps arising. On one hand, Davies Manor is cast as the center of an idyllic, prosperous rural community. On the other hand, it seems scarred by upheavals, personal struggles, and violence. Did you find yourself wrestling with how to tell this story?

Ross: Yes, absolutely. Initially, I saw the project more as a straightforward extension of an exhibit that we opened at Davies Manor in 2019. I was coming at it more from an interpretive standpoint focused on this one collection of plantation papers. But the deeper I got into the outside materials about earlier generations of the family, the more I shifted toward a narrative-driven approach that tried to situate a micro-history against larger historical events.

I also realized that this was a chance to juxtapose, through virtually the whole of American history, competing versions of the same story — one rooted in nostalgia and lore, and the other in primary records. The contrasts between the history as it had traditionally been presented and what actually occurred kept smacking me in the face. So hopefully readers can get a sense for that.

Chapter 16: You have worked at Davies Manor and remain a public historian. What are the responsibilities when telling the story of a former slave plantation? What does the site owe the public, in terms of its historical presentation?

Ross: Across the public history landscape, many former sites of enslavement have transformed the stories they tell and worked to centralize interpretations of slavery. There are certainly best practices for this sort of work and shared lessons that can be gleaned. But every site has to grapple with its own unique circumstances, challenges, and responsibilities.

At Davies, important steps have been taken toward presenting a more complete and nuanced history. That happened before and during my time working there, and it’s still happening. But I also think much remains to be done, especially in terms of really deconstructing, in a forthright way, the realities and long-term implications underlying the site’s founding. Davies Manor, like Ellen Davies-Rodgers, has historically meant very different things to different communities of people. The reality is that the site and its founder played a role for many years perpetuating values and ideas grounded in white supremacy. So as time goes on, I think the site does have an obligation to confront those things head on from an institutional standpoint. Rather than viewing certain topics as vulnerabilities to be glossed over, I wonder how they might be approached as opportunities.

I see Davies Manor as having the potential to be a critical part of the evolving conversation on how history, collective memory, and community identity have been shaped in Memphis and Shelby County.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.