A Special Relationship

Writer and translator Adria Bernardi discusses her work and her unique linguistic heritage

Adria Bernardi was born into an Italian-American family and community in Highwood, Illinois, a small city north of Chicago. She grew up there surrounded by a rich language culture that combined Italian, a regional dialect, and Midwestern English—a unique patois she calls “Highwoodese.” Bernardi has explored her the immigrant experience and her own heritage in her novel, Openwork, and in the oral history Houses with Names: The Italian Immigrants of Highwood, Illinois. Her other books include a novel of sixteenth-century Italy, The Day Laid on the Altar, which won the 1999 Bakeless Fiction Prize.

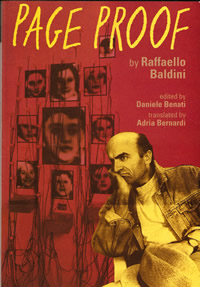

Acclaim for her own writing is matched by high regard for her skill as a translator. In 2009, she published both Siren’s Song, a translation of the prose and poetry of Rinaldo Caddeo; and Small Talk, a collection of poetry by Raffaello Baldini, who wrote primarily in the Romagnole dialect. Bernardi, a recent transplant to Nashville, has taught in the M.F.A. program for creative writing at Warren Wilson College, and at Clark University. She answered questions by email about the challenges of translation, her own relationship to language, and the parallels between Southern literature and the regional literature of Italy.

Chapter 16: Your fiction and your choice of texts for translation have focused on Italian or Italian-American subjects. Can you give a thumbnail sketch of your own heritage, and explain a bit about what that language and the culture of Italy mean to you?

Bernardi: Talking and listening, and the counterpart of non-listening, is one theme of Small Talk, which is comprised of four collections of Raffaello Baldini’s poetry. The quality of listening and hearing imperfectly—whether it’s hearing small talk from a distance through some obstacle that blocks or distorts or yields it an altered form, as gossip does, or in the veiled way of a dream—is found in many of the poems, as in this one, “Noise”:

… it’s like in sleep, when you’re feverish,

in the bed upstairs,

you’re hearing those women downstairs chatting away, you don’t understand a thing

but you recognizes the voices,

it’s the same thing there,

it’s a pandemonium,

it seems like it’s a street-bazaar, but then instead you start to hear something …

Throughout these poems, there is a steady reference to words and expressions themselves for talking, speaking, hearing, calling out to someone, shouting. In many poems, no one hears anyone or anything. Silence and noise predominate. In poem after poem the individual in community is in isolation amidst chaos. This way of approaching these poems, this way of hearing them, of being with them, and of translating them, has everything to do with my particular relationship to the Italian language and to translating. My relationship with Italian, with the dialect, is fragmented. It was learned in fragments. Translation is a means of reconstructing a whole. It is a re-activating the way I learned to speak, perhaps by engaging the most generative parts of myself.

Throughout these poems, there is a steady reference to words and expressions themselves for talking, speaking, hearing, calling out to someone, shouting. In many poems, no one hears anyone or anything. Silence and noise predominate. In poem after poem the individual in community is in isolation amidst chaos. This way of approaching these poems, this way of hearing them, of being with them, and of translating them, has everything to do with my particular relationship to the Italian language and to translating. My relationship with Italian, with the dialect, is fragmented. It was learned in fragments. Translation is a means of reconstructing a whole. It is a re-activating the way I learned to speak, perhaps by engaging the most generative parts of myself.

Here is an insight: in the past few years, I have come to understand that there is a certain calm that overtakes me, particularly at times of great breakage or loss, when I am in the middle of a room, usually a domestic place, or at least a place where I feel at ease, a sense of being part of those gathered, welcomed yet at once peripheral to it. I am certainly not at the center, but, rather, sitting back and listening to a language I do not fully understand.

However, it is as if I do understand and begin to listen to the back-and-forth, listening for who-says-what-to-whom, who speaks more, who dominates, and how; listening for the jokes, who says something nasty, who says something kind, who agrees, who withdraws. I start to find words I recognize, I differentiate words of different languages—another dialect or tribal language. I recognize if someone cringes or lights up at a certain word being said. I track the word when it is said again. Occasionally somebody will remember I’m sitting there and say something to me; then they’ll go back to whatever it is they’re talking about. I realize I am profoundly content. It is this same calm that occurs as I translate. It is physiologic; it is neurologic.

I understood that, sitting there in a small living room, I was again a child, surrounded by small talk in three languages. I realized this as I was sitting, off-and- on, during the course of two weeks while mourning for a friend whose family is Kikuyu, as they waited for the arrival of her parents and sisters to arrive from Kenya. In these evening gatherings, prayers were chanted in Kikuyu, and then, after the spiritual gathering was done, the group re-grouped into a more relaxed, or relieved, state of conversing, of conversation.

It went back and forth from Kikuyu, lapsing into Swahili, with English, (Kenyan-Massachusetts-English) thrown in. The place names I could understand, for we shared the landscape—Worcester, Massachusetts. Certain expressions came in which I could understand, because they were universal, iPod, Taco Bell, for example. The names—Joseph, Neil.

It went back and forth from Kikuyu, lapsing into Swahili, with English, (Kenyan-Massachusetts-English) thrown in. The place names I could understand, for we shared the landscape—Worcester, Massachusetts. Certain expressions came in which I could understand, because they were universal, iPod, Taco Bell, for example. The names—Joseph, Neil.

I understood then that I knew how to weave my way along in these settings and that it was elemental to me, and that it sustained me. In a certain way, it was as if I convinced myself I understood both languages, both Kikuyu and Swahili, because I understood so much of what was going on. I could read the languages; I could hear, when it switched from Kikuyu to Swahili. I could sense how the tenor of the conversation changed, the topic changed, who was speaking it, and why.

I understood, then, that this was my childhood. This was my way of listening, watching, and participating, and had always been. It was at once a very fragmented kind of language; I, of course, had no understanding whatsoever of either language; it was filled with holes. I also, paradoxically, had a profound understanding of the conversations and an accurate read of much, maybe the most important aspects of the event, that which regarded my friend, Veronica, and her family, who was peripheral to her, who was important to her.

This is how I learned language, English, Italian, and dialect, and all of it together. This is how I first learned language, for those who sustained me, spoke all of these languages, all at once. My grandparents all spoke “the dialect,” as it was called by my parents. Three of them spoke it exclusively and did not speak Italian. My maternal grandmother spoke both standard Italian, as well as the dialect. My mother’s first language was Italian; my father’s first language was dialect. My mother does not speak a dialect. She and her mother spoke to each other in Italian; my mother’s parents spoke to each other in dialect. My father spoke to his parents in dialect; his parents spoke to each other in dialect. The dialects of my grandparents were technically the same; yet they were from different towns, and these towns had very different words and different gestures. They sounded different. My parents did not speak Italian to me. My grandparents spoke in Italian or dialect to me.

My language was learned in parts, in English, Italian, and in dialect; many children learned it, and learn it, as I did. I suspect many translators do, and that this may be, in part, what draws them to a lifetime of translating, and to this kind of remaking, to reviving these routes in the brain. It is similar, I think, to the way a physician needs to continue healing others, and the way and this need arises out of early wounds and early perceptions of being wounded or witnessing others in pain, and believing that he or she is able and capable of relieving distress. This, I have come to believe (or have come to tell myself this story) is how I learned to speak—by sitting among people older than me who were speaking Italian, different versions of the same dialect, and English, and a kind of broken Midwest-, Chicago-English I call Highwoodese. Each immigrant, refugee, exiled, displaced community all over the globe has its version of it.

I am the first grandchild on both sides. I was born in 1957. My brother, Ron, is the second grandchild on both sides, the first grandson. He was born in 1958. My mother lived with her mother in Italy, and joined her father in the United States when she was school age. And so my mother was formed in Italy until age seven, where she went to school during the 1930s. She and my grandmother left Italy in 1939. She has two sisters who are significantly younger than she is, and the family in the United States which redefined itself and was a new family, in language and in culture. By seven years old, so much of ourselves has been already made.

My paternal grandmother was the last-born child of a very poor woman, of a very fractured family. Her husband committed suicide. She was a widow with two children. The eldest son emigrated to work in coal mines when he was thirteen. A third son was adopted by a couple in a foreign country. Her eldest daughter developed polio. My grandmother never knew or never revealed her father’s identity and was raised in an extended family by a single mother.

I was much doted upon, and also aware from the earliest moments of these breakages. My work as a writer has been preoccupied with fragments, and with leavings and departures, first an oral history, Houses with Names: The Italian Immigrants of Highwood, Illinois, and then two novels, both of which begin in the Apennine mountains and involve fragments, the departure and remaking of a whole through some kind of sustained endeavor.

Chapter 16: Most translators of poetry are themselves poets. Is it necessary to possess the skills of a poet in order to be a good translator?

Bernardi: I might prefer to think of it as having to do with relationship. A reader of a poem or of a group of poems, a body of work of a particular poet, decides at some level that he or she needs to bring this poem into his or her language for some other reader. He or she understands it at a profound level in the original, at the literal level, and wishes to bring it into another language.

Bernardi: I might prefer to think of it as having to do with relationship. A reader of a poem or of a group of poems, a body of work of a particular poet, decides at some level that he or she needs to bring this poem into his or her language for some other reader. He or she understands it at a profound level in the original, at the literal level, and wishes to bring it into another language.

Why? Why one work and not another? Perhaps he or she finds a dialogue is already ongoing and that associations are already being made to bring it into his or her own language. The brain is already scanning for phrases. This, I would suggest, is a spontaneous response. It can’t be directed. That I could hear the timbre of the voices of those women upstairs talking, the sound of the echo in the stairwell, and the associations of which word, and which phrases, would bring line after line into a kind of Baldini language, can’t be planned for, and it suggests to me that I have an understanding of the language of this poem.

The kind of thinking that is essentially associative is a kind of movement that belongs to the poet. It doesn’t belong to other kinds of activities. It is a place of joy. This isn’t to say all parts of translating are associative—many essential parts are very deliberative, structured, organizational in nature; they involve discipline, craft, things like counting, and deliberately researching, and laying out patterns—for example, going through and seeing how many times the “sh” sound occurs and where it is falling, how to sequence, or what the number patterns are. Will a poem’s title have an article, and how does that work with the overall strategy of the book? Other choices came down to etymology and involve very directed research. But often a phrase emerges because the word and the image come together at the same time after all this work, and when this kind of association occurs, there is no planning for it, how one element will associate with another.

That said, wouldn’t one have to have an intimate relationship with words and letters and syllables, with punctuation marks, and line lengths, and sounds, and how those things translate into another language, where the choice is infinite, and the only way to decide is based on your relationship with language, the meaning of the text, based on your reading of that text according to your understanding of language? That’s what a poem is. Wouldn’t one have to have that relationship with the literatures of each of the languages? You’d have to care about idiomatic expressions and why one voice would use one expression and another wouldn’t. Then you have to step back from it, have the discipline and a healthy-enough ego, to step back away from it, because it’s the poem that counts—not the poet or the translator. But why would you do it if you didn’t care why he or she used that word? You have to care about the semicolon versus the dash. What’s the point otherwise? It’s how the thing’s made.

Chapter 16: How far should a translator wander from the literal translation of a poem in order to make it comprehensible across cultures?

Bernardi: In my translations, I’ve tended to not wander very far at all from original. I do not think of them as my poems. I do want to see my name on the front of the book because a translator’s work must be honored. The translation itself, however, belongs to the original poem.

Like most translators, I want the reader to forget that it’s a translation, and I hope he or she will have that momentary sense of displacement while reading that this is the original voice. The translator must recede. Part of what determines how I make a decision includes whether a particular choice might be calling too much attention to itself. Challenges include what to do if there is no choice for a contemporary term or a regionally specific term. Another challenge in these translations were place names and also proper names that involved diminutives, or possessive qualifiers that also conveyed an individual’s identity within the wider community—a name like Gero dla Zoppa.

I stayed very close to the form of the original of Small Talk. For the most part, lines breaks fall wherever they fall in the original. Many of the poems are internal monologues in which the speaker is in a headlong rush; he or she frequently speaks frenetically, in an out-of-control, obsessed tirade. Regardless of where the line breaks fall in these poems, the poetic segments can usually be found between the commas—in the association between the sounds, in the rhetorical patterns that bounce against each other, and in sequences. Repetition in language, in imagery, in syntax, in lexicon is one of the main ways that these poems are formed. The title is also a clue to the meanings — Small Talk — it’s banter, it’s chitchat.

The form of the poem is made by what is internal to it. And so I adhered almost exactly how it was composed: each digression of the speaker, each left-off phrase, each incomplete digression—these rhetorical devices serve an essential purpose both in revealing the speaker, but also in holding the poem itself together. Many an editor, or reader, might want to say, “Cut! Redundant! Confusing!” No. It’s what holds it all together. In all the drafts, up until the final revision of putting the book together, I had virtually every comma as in the original. Most of the lines were as in the original. Only at the end did I decide I could move around the order of poems and change punctuations.

One decision involved sentence length in the first lines of certain poems, in which the first line ended with a comma, and [I changed] it to a period. Accumulating clauses linked by commas are at the heart of Baldini’s poems. Shouldn’t the comma be sufficient to suggest the inflection? Shouldn’t the reader be able to “hear” the signal to pause? In a number of poems I decided to use the short sentence as a way to signal emphasis. In certain cases it was a question of highlighting a strong declarative sentence or nuancing an exclamation. One example is in the poem, “Travelling”: You go ahead, you travel, I’m fine where I am./ (Mo viaza tè mè a stagh bén dò ch’a so,/) (Ma viaggia tu, io sto bene dove sono,/)

After working on the Baldini translation for so long, which I have come to understand as a dedication to understand parts of origins, translating Rinaldo Caddeo’s, Siren’s Song was very freeing. They are marked by a different kind of kinetic energy, with poems that appear in more restricted form. The poems are very much on the intellectual axis. They are irreverent. They are very ephemeral. To translate required that I invent—phrases and, a few times, words—so it gave me a kind of permission to let the neural sparks fly a little.

Chapter 16: What were the particular challenges of the translating you have done? How easily does English accommodate Italian and the dialects you’ve worked with?

Bernardi: In certain respects, the Romagnole dialect of the original poems was better suited to American English than the Italian was. The Romagnole dialect is not a particularly beautiful language. I don’t think you find people saying, “Oh, it’s such a beautiful language; I really want to learn it, it’s so melodic,” as they do with Italian. Unlike Italian, it is a language with monosyllabic words, full of diphthongs. There are many words that end in consonants. For me, the template is the sounds of Chicago and the Midwest. I matched syllables and sounds, and it was as if I could match a combination of Emilia-Romagna with immigrant, working-class, suburban Chicago and Midwest, and also the mountain towns of Emilia-Romagna, and also Worcester, Massachusetts, and its poets, which is where I was living, and had lived, for twelve years.

An example of this can be found in a particular word choice, in the second line of “The Cricket.” The sentence is an imperative: “Just listen to that cricket singing away,/ (Sint cm’e’ ch’ènta che gréll,/) (Senti come canta quell grillo,/).” Something has put him at odds with the cricket, not quite disparagingly, but almost as if he is calling out to someone to join in to deride the happily singing cricket, which will later on accentuate the feelings of isolation and his pain.

In the second line: “he’s really going at it with gusto, (u i dà ès te s’una pasiòun, … /) (ci dà s’una passione.)” I opted to translate passion as gusto. Passion is clearly a word with a more literary lineage. But in the dialect, it also is used in common-day language. “E ga passion”: it can mean lots of things: “He or she has heart. A love of life. Verve. He’s such a mensch.” The cricket is chirping, and this man is alone at night in his balcony garden searching for it; he’s annoyed; he’s out of sorts. He is arguing, cajoling, coaxing the little cricket to show itself, this grillo.

Then he starts arguing with himself, with the cricket–antagonist. What is the word to use, then, if not passion or something along those lines? Enthusiasm? Energetically? What does that word sound like? Which word will resonate with what the original poem sounds? With its dominant sounds? What would the speaker say to himself about this little cricket? He would say gusto. He would say, Going at it with gusto. Gusto is also a nice two-syllable word, a trochee, with a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, which is just like many other words in the poem, like basta, (enough), chènta, (singing), nòta (night), spétta (wait), écco (here it is), bòssla (door leading to the balcony); it is a dialect word with its choppy sound and with a consonant blend in the middle. It’s a hearty-yet-harsh word, with some energy and pent-up anger in it. It’s frothy, like a beer commercial. I wouldn’t use it, but he would. He’s of this generation, born 1924. So I think that English works pretty well.

Chapter 16: In your introduction to Baldini’s poems, you write about about a feeling of “enclosure” that the language carries because it is spoken in such a limited community with a particular history. You compare a writer like Baldini to writers of the American South, such as Flannery O’Connor. Do Italy’s regional writers enjoy the same high regard that Southern writers in the U.S. have received?

Bernardi: These poems, I would argue, were written by a poet whose stance in life was formed early, as a listener, in an enclosed space. He was a child who grew up in his family’s café in the town of Santarcangelo in the province of Rimini during the 1920s and 1930s in Italy. This is Fellini’s terrain, although this is a completely different witness. Raffaello Baldini was born in 1924 in Santarcangelo di Romagna in the province of Rimini. That same year opposition leader Giacomo Matteotti exposed and denounced Fascist corruption in parliamentary elections in a parliamentary speech on May 30, demanding that they be annulled, and was abducted and murdered in Rome.

Benito Mussolini achieved his stranglehold during the next year: opposition leaders were arrested, press censorship was in place, and parliamentary rule had ended. When I used the term “enclosure,” I referred to these external realities, to the social and communal boundaries of institutions that functioned and existed under the constraints of a fascist regime for nearly a quarter of a century, and of a youth that was bookmarked, by two wars, of living within a small town, where the language of that town is not understood outside that town, and of internal discourses of an enclosed community that remain internalized and become externalized in particular ways:

1938

Sometimes in the afternoon,

the schoolteacher from Sant’Ermete

closes herself up in her bedroom and lights up a Giubek.

She doesn’t smoke.

Stretched out on the bed

she watches it burn.

She likes the odor.

Sometimes

she feels like crying.

Raffaello Baldini left Santarcangelo as an adolescent to attend the liceo in Rimini. Relative to everyone else in town, he was privileged, and certainly the surrounding countryside, where the majority of adults were illiterate. He studied philosophy at the University of Bologna. He went on to work in advertising, in Milan, and then journalism for the newsweekly Panorama, reporting on the Vatican and as an editor. He did not begin writing poetry until he retired.

There is a generation of dialect poets whose childhoods were marked by two wars, by the years of fascism, by the years of persecution of Jews and the Shoah. Italy of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s was essentially a country of rural villages of illiterate peasants, in countrysides largely depopulated by immigration; this changed with the introduction of mandatory education and it changed following the end of the Second World War. The language of the dialect belongs to a period that precedes the Second World War; however it exists, after that, in whatever form, spoken, imagined, art— it is fragmented, suspended, and forever out of time.

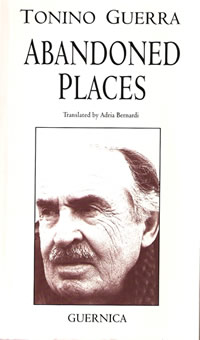

Other dialect poets emerged from Santarcangelo, including Nino Pedretti, and poet and screenwriter, Tonino Guerra, two years Raffaello Baldini’s senior, who began to write dialect poetry while imprisoned in a German concentration camp. All of Baldini’s poetry, as is Guerra’s, was written in the dialect of Santarcangelo. It is, he said, the only language in which he could have written poetry.

The sense of enclosure also refers to a sense of imposed silence. Many of the speakers are isolated within this community. Most of the speakers speak no other language. Some choose not to join with others, as in a poem like “Solitaire.” In others, mental illness isolates the individual. For other speakers, it is the process of aging and the changes within the community itself.

Some poems remind me of Eudora Welty’s story, “Why I Live at the P.O., ” in the sense of place acting on individual, with the enclosure of the house; a small town is absolutely closed to outsiders, and others inside the house use language as weapons that include gossip and innuendo. In the Eudora Welty story, as in so many of the Baldini poems, the speaker speaks and speaks and speaks, in an unbroken monologue, in argument, to unspecified interlocutors, with twists and turns that are nearly impossible to follow because there are so many arguments going on at once in an enclosed space where the pressure builds. It is almost impossible to tell the truths from the lies, which is why the there are so many ways people read the story.

Other poems are the story of a grown child and parent, usually again told using a confined space in a short time span, and suggesting quickly and deftly, often in dialogue, how they have locked into an enclosed and compressed life. One such poem in Small Talk, is “Traviata,” where the mother goes to tell the son his friends are waiting downstairs in the car for him:

[T]hey started honking, I didn’t say a word,

“People, it’s five-thirty,” my mother

came out of the kitchen: “Bruno, they’re talking to you,

and you’re not budging? are you sick” “No,”

“All right, answer them then,

because if you wait any longer,

Don’t say anything, let them go,

“What’s wrong, did you argue with someone?”

“A fight? with who” she looked at me. “What’s going on?

first you’re frantic to go, and now, who can understand you,

do you hear? they’re leaving, that’s right, run to the window,”

I stood there awhile, pressed against the glass,

pleased, I flopped down on the bed, my shoes

were pinching a little, I changed them,

a sweater, jeans, “Don’t wait for me tonight. …”

It reminds me of a story of like Flannery O’Connor’s “Everything that Rises Must Converge,” in which every word, spoken and thought, in the enclosed spaces of that story, directed toward mother and son Julian, reinforces the sense of the one having made the other smaller and meaner, smaller and meaner, at every turn.

It’s as if the whole pressure within that small bedroom will enclose the reader along with both of them. It reminds me of a story of like Flannery O’Connor’s “Everything that Rises Must Converge,” in which every word, spoken and thought, in the enclosed spaces of that story, directed toward mother and son Julian, reinforces the sense of the one having made the other smaller and meaner, smaller and meaner, at every turn. As in so many of the Baldini poems, there is no escape clause for these speakers. Again, the reader will read the story in different ways and hear the dialogue in different ways.

Chapter 16: Sticking with the subject of regional literature, there’s a widely held belief that Southern literature is dead, or dying. Are similar statements made about the regional literature of Italy? Can there be such a thing as a regional writer anymore?

Bernardi: This is an excellent question. I don’t know the answer. I can say that there are many translators translating dialect poetry and that there is a complex and thriving discussion about the translation of dialect and relative to Italian cultural, literary and intellectual history and most of the critics have written about it because it touches upon the essential questions about why certain poets stand the test of time and why certain kind of poet language only scrapes at the surface. There is no discussion about Italian cultural identity that does not involve the Italian language. The two can’t be separated.

There are is a two-volume anthology of dialect poetry edited by Achille Serrao and Luigi Bonaffini, Dialect Poetry of Southern Italy and Dialect Poetry of Northern Italy, that includes translations by poets who live all over the world: that is to say, those who speak Italian, who have ended up in many places by who wrote poems in a dialect as a result of that breakage called leaving, by whatever form it originally took. These collections bring together about 400 poems by about 115 poets who write in one of 20 Italian regional dialects, which are by no means the same within each region. Like other translations of Italian dialect poetry, they are trilingual, which means that they include both the original poem in the dialect, as well as a translation in the standard Italian. Among the important Italian dialect poets who may be already known to readers who don’t know Italian, or who are not Italianists, are Pier Paolo Pasolini, Franco Loi, Andrea Zanzotto and, Tolmino Baldassarri. Other dialect poets include Cesare Pascarella, Trilussa, Joseph Tusiani, Dante Maffei, Mauro Marè, Giose Rimmanelli , Albino Pierro, and Emilio Rentocchini.

Insofar as the dialect, there is are two different kinds of currents flowing, one of which has nothing to do with poetry. One is essentially political in nature and is tied to political institutions and the desires of those who seek to revive regionalism, some seeking to have their particular region cede from the nation, and some suggesting that a particular dialect as an “authentic” language to which a particular culture should somehow return. Looking back with nostalgia at the contadini and the language of the regions, with cultural values, and the people of the land, and the integrity of the province, is a double-edged sword: the rise of provincialism, as is the movements of populism, can be an ugly little creature; American literature has its own works of literature that has turned its gaze toward this phenomenon. I’m thinking here of All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren.

Insofar as the dialect, there is are two different kinds of currents flowing, one of which has nothing to do with poetry. One is essentially political in nature and is tied to political institutions and the desires of those who seek to revive regionalism, some seeking to have their particular region cede from the nation, and some suggesting that a particular dialect as an “authentic” language to which a particular culture should somehow return. Looking back with nostalgia at the contadini and the language of the regions, with cultural values, and the people of the land, and the integrity of the province, is a double-edged sword: the rise of provincialism, as is the movements of populism, can be an ugly little creature; American literature has its own works of literature that has turned its gaze toward this phenomenon. I’m thinking here of All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren.

The dialect poetry of Raffaello Baldini, is written from the most internal language of the writer, out the places of most brokenness and healing of place and self; it is written for others, outside themselves, and outside the boundaries of a limited place; the idea that, as Baldini has called it “a small language,” an “oral creature,” would somehow be used to silence others—to put down or to denigrate whole groups of others—would be like asking that cricket to become a mouthpiece for saying spite.

In a review of Small Talk, poet Davide Argnani describes dialect in this way: “Dialect was the Language of our Ancestors. It was the Language of the culture of the contadini. After centuries and centuries, fighting and wars, suffering and poverty, of scorn and injustices, the civilization of the contadino disappeared in the heart of the last century, right after the end of the Second World War. Somewhat out of nostalgia, somewhat to get even, somewhat out of love for the disappeared language, the only conservators of the alphabet of the fathers remaining today are the Poets, yes, precisely those with the Capital P. Without rhetoric or self-pity, the poets are the ones who knew and know how to speak with the dead Language of a disappeared civilization.”

I have come to think of these poems as a way of understanding: “Here is how I didn’t hear you.” One of the final poems, “Who’s There?” (Chi parla?)” is about a subterranean conversation going on in town: some people are getting phone calls from deceased loved ones. They are in conversation with one another about it. Did you get a call? So did I. Has he called back? Me neither. She got one. And of course, it degenerates into gossip, and sniping, and regret. It’s Pirandello, Kakfa. It is painfully absurd; it presents anguish, as the speaker, without raising his fist, is asking the Great Question with the great above and the switchboard operators, asking why he can’t have the connection with the loved one for just a few minutes longer:

where are you? they’ve disconnected me, my God, they’re zealots,

right to the exact minute, just keep it open,

for a couple of more words, what could happen?

and then the first time, why do they have to be there

with a gun to your head, it’s that they’ve got, who knows,

they’ve got their orders too, it’s hard though,

three minutes? come on now,

what can you do with three minutes? …