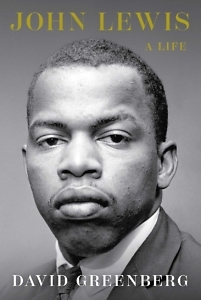

A Steely Commitment to Change

Historian David Greenberg explores John Lewis’ lifetime of making good trouble

Among the civil rights era’s holiest shrines is the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where demonstrators famously confronted a hostile all-white police force on March 7, 1965. Images of the officers’ brutal attack against the peaceful protesters on “Bloody Sunday” shocked the country and galvanized support for the Voting Rights Act later that year. One of the leaders of the protest march that day was a young Baptist minister named John Lewis. In his sweeping, scrupulous new biography, John Lewis: A Life, historian David Greenberg recreates the moment when Lewis collapsed amid a police fusillade. “A trooper’s club knocked [Lewis] hard on the left side of his skull … Blood ran down his head. The world began to spin.”

That day Lewis learned how to make the world spin to his own ends. Perhaps no politician emerged from Selma with as steely a will to compel racial change. His career in public affairs spanned over 60 years, and he came to embody past, present, and future. Greenberg’s account is dutiful yet solid in its interpretations, teasing out how Lewis’ lifelong religious principles and moral compass guided him from decade to decade.

Born in 1940 on a farm outside rural Troy, Alabama, three generations from Emancipation, Lewis was a thoughtful boy, something of a bookworm. As a child he felt anointed to something larger than himself; he preached to the chickens and later to Methodist and Baptist congregations. The murder of Emmett Till in 1955 stirred him, as he cojoined his faith with a desire for equality. Two years later, he matriculated at an all-Black seminary in Nashville, a city afflicted with the nation’s original sin but struggling to distinguish itself from Bull Connor’s Birmingham and KKK-inflected towns. “Forty-three percent Black, Nashville was the most tolerant city in the South,” Greenberg observes. “As the activist minister Cordy Tindell (“C.T.”) Vivian said of Nashville’s liberals, ‘They tried to set a tone far different than most cities. … Even so, Black Nashvillians endured second-class treatment, racist humiliations, and stunted opportunities.”

Lewis fought for desegregation of lunch counters, quickly catching the notice of fellow pastors and organizers. As a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he was soon working with Vivian, Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, and other luminaries, later picking up the torch after King’s assassination in 1968. The man met the moment, throwing his weight behind Robert Kennedy’s late entry into that year’s presidential race; he was ensconced in a room at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles when Kennedy was cut down in the kitchen by assassin Sirhan Sirhan, just following the primary victory in California.

After Lewis’ marriage to Lillian Miles at Ebenezer Baptist, officiated by Martin Luther King Sr., the couple settled in Atlanta. Greenberg astutely underscores the policy concerns that crept out of Lewis’ activism, from voting rights to education to environmental protections. When Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 elevated Atlanta Congressman Andrew Young to U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, the ever-ambitious Lewis tossed his hat into the ring to fill Young’s seat. In an uphill contest, he “portrayed himself as both an agent of and a testament to the egalitarianism that made Atlanta prosper.” A New South was eager to showcase a vitality and fresh engagement with social justice. Greenberg tracks this pivotal period with shrewd analysis and a novelist’s pacing. Lewis lost the race but found a spot in the Carter administration, and in 1981 went on to his first victory as a representative on Atlanta’s city council, “the body’s most outspoken member, but also one of its most polarizing.”

After Lewis’ marriage to Lillian Miles at Ebenezer Baptist, officiated by Martin Luther King Sr., the couple settled in Atlanta. Greenberg astutely underscores the policy concerns that crept out of Lewis’ activism, from voting rights to education to environmental protections. When Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 elevated Atlanta Congressman Andrew Young to U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, the ever-ambitious Lewis tossed his hat into the ring to fill Young’s seat. In an uphill contest, he “portrayed himself as both an agent of and a testament to the egalitarianism that made Atlanta prosper.” A New South was eager to showcase a vitality and fresh engagement with social justice. Greenberg tracks this pivotal period with shrewd analysis and a novelist’s pacing. Lewis lost the race but found a spot in the Carter administration, and in 1981 went on to his first victory as a representative on Atlanta’s city council, “the body’s most outspoken member, but also one of its most polarizing.”

Greenberg balances vibrant political history with Lewis’ complex persona and values, particularly his fiery commitment to his constituents. The 1986 congressional primary pitted him against his best friend, Bond, whose cocaine addiction and subtle political differences — as well as a vituperative run-off — tipped the election to Lewis. A legend took flight as the newly minted congressman wielded his “moral authority” as his “sharpest weapon.” The second half of John Lewis maps his triumphs and setbacks on Capitol Hill, where he cultivated often uneasy relationships on both sides of the aisle while mentoring a new generation of Black figures, including Barack Obama. Lewis increasingly fell back on his reputation as a hero, leveraging it to muster gains for laws and politicians alike. His final years cemented his status before his terminal diagnosis of cancer and his death in 2020.

John Lewis: A Life is never worshipful but rather approaches its subject with investigative curiosity and rigor. Greenberg gives us the complete view without bogging down in minutiae, a solid account of one Alabama farmboy’s journey and enduring impact on our people.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for O, the Oprah Magazine; the Minneapolis Star Tribune; and The Barnes & Noble Review. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.