A Story in Every Plate, a Plate in Every Story

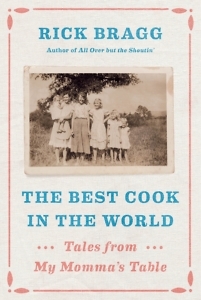

Rick Bragg is back with another family memoir—this time with recipes

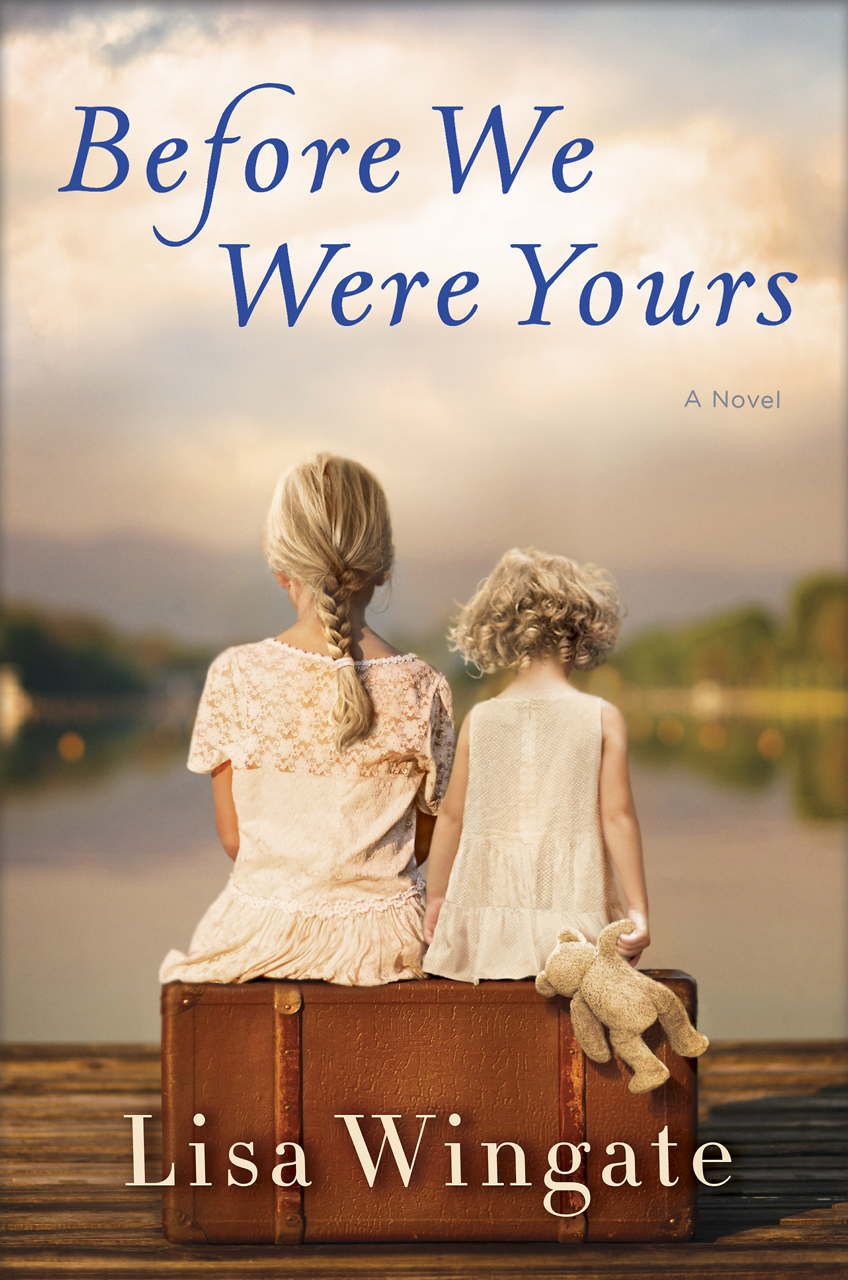

Rick Bragg’s fans may feel well acquainted with the family he has chronicled in bestsellers like All Over but the Shoutin’ and Ava’s Man, among others. In his new book, he homes in on his mother, Margaret Bragg, as well as his grandmother, Ava Bundrum, and her children, Bragg’s aunts and uncles. His subject in The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table is the family’s foodways—its long legacy of Southern cooking, its relationship with food through hard times and flush seasons, the recipes and kitchen savvy handed down generation upon generation.

The Best Cook in the World is “listen to this” writing, the words I’ve said to my husband repeatedly while reading this book: “Listen to this part.” Before reading this book, I didn’t imagine that the preparation of baked hog jowl could make for riveting reading. The same goes for depictions of making a pot of beans, or cornbread, or collards. All tasty enough things to eat, mind you—well, I can’t claim firsthand experience with hog jowl—but I can’t say I anticipated that great entertainment could come from a play-by-play of their creation.

That was before I read Rick Bragg. “I knew I had to convince her to let me write it all down,” he writes of his mother, “to capture not just the legend but the soul of her cooking for the generations to come, and translate into the twenty-first century the recipes that exist only in her mind before we all just blow away like the dust in that red field.”

He begins by spinning tales of his great-grandfather Jimmy Jim, “the mean old man,” who taught his grandmother Ava Bundrum to cook. Before Bragg’s momma took on the mantle of best cook in the world, there was her momma, Ava; and before that, her momma’s father-in-law, and so on back through time. Bragg shares Margaret Bragg’s cooking with readers through the stories behind the suppers, meal by meal, cracklin’ cornbread by butter roll, poke sallet by pan-roasted pig’s foot, cider-roasted chicken by creamed onions “so tender they slipped through the tines of the fork.”

Or is it the suppers that serve up the stories? A classic chicken-egg scenario, but really there’s no need for debate—just pull up a chair and take it all in. In Bragg’s storytelling, in his language, those kitchen scenes are deeply satisfying, sensuous and funny and action-packed:

Then he showed her how to make the dish that complemented it all. He showed her how to thin-slice the white onions and a few green onions and put them on to cook in just a daub of bacon grease and a little butter, bring them to a quick sizzle to get the flavors working, but cook slowly from then over low heat.

“You don’t want fried onions,” he said. He showed her how to make them go soft in their own sugars by slowly adding spoonfuls of water and covering them with a lid, so that they did not fry or steam so much as just kind of melt in the butter and pork fat.

There’s also a tremendous scene set during a tornado that just dodges the family shack, but the everyday-cooking passages are every bit as compelling. “I guess you would call it a food memoir,” Bragg writes, “but it is really just a cookbook, told the way we tell everything, with a certain amount of meandering. Even the recipes themselves will meander, a little bit, because a recipe is a story like anything else.”

There’s also a tremendous scene set during a tornado that just dodges the family shack, but the everyday-cooking passages are every bit as compelling. “I guess you would call it a food memoir,” Bragg writes, “but it is really just a cookbook, told the way we tell everything, with a certain amount of meandering. Even the recipes themselves will meander, a little bit, because a recipe is a story like anything else.”

Bragg doesn’t shy away from casting this as a celebration of his mother, the very antithesis of the South’s celebrity chefs today (them that boast “more pierced nostrils than a root hog,” as he tells it), and all that her cooking stands for: the South, the fortitude of working-class and poor Southerners, the importance of family ties and shared histories, and a stubborn dedication to the old ways of doing things. His mother’s food is “the food of the high places, of the foothills, pine barrens, and slow, brown rivers,” he writes. “She never cooked from a written recipe of any kind, and never wrote down one of her own.”

The people who taught her the secrets of Southern, blue-collar cooking are all gone now, and they did not cook from a book, either; most of them did not even know how to read and write. Every time the old woman stepped from her workshop of steel spoons, iron skillets, and blackened pots, all she knew about the food left with her, in the way, when a bird flies off a wire, it leaves only a black line on the sky.

For a writer, Bragg’s themes present a specific kind of challenge, for how do you talk about such matters without resorting to cliché or beating the drum of nostalgia? How do you talk about the South, after all, and make it new?

Through poetry and the beauty of simple, direct language. Through a well-placed quote from his central character, whose words perfectly season the recipes.

Truthfully, I’m not always sure how Bragg pulls it off. But what he offers here is no less than a virtuoso performance, a combination of voice and true affection and the occasional whang—that’s a word I picked up from this book—of wise-assery. “My mother believes you can tell if a thing was cooked right by listening as people eat it. Any sound a fried food makes should be crisp, maybe even delicate. A group of people eating fried chicken should not sound like someone smashing a glass-topped coffee table with a ball-peen hammer.”

Food, Bragg writes, “is one of the ways we keep the calendar down here. … [A]t our table, it seems there was a story in every plate, and a plate in every story, except maybe artichokes. Nobody liked to remember the artichokes.”

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch Writers’ Collective, a nonprofit literary center. She is the author of This Will Go Down On Your Permanent Record, a novel, and numerous journal and magazine articles.