Abundant Goodness

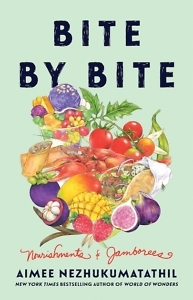

Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s Bite by Bite is a nourishing, lyrical sampler

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on April 25, 2024.

***

It’s a common experience: walk into an unfamiliar place and a familiar scent transports you back in time. Perhaps it’s to your grandmother’s kitchen as she taught you to make biscuits or maybe to your first apartment, the tiny one over the delicious Indian restaurant that taught you to love curry. Maybe the scent takes you to the church basement where long tables were spread with every dish imaginable, including Mrs. Taylor’s famous lasagna. Our sense of smell has a remarkable ability to unlock memories, so it’s no surprise that many of our memories are tied to food.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil certainly agrees, and her latest, Bite by Bite: Nourishments and Jamborees, is a veritable smorgasbord of flavors, from mint and mango to shaved ice and halo-halo. It is also, of course, a multi-course menu of memories, as Nezhukumatathil uses these foods as a way to share stories of her past, her family, and her culture, as well as insistent wonder at and encouragement to notice the goodness abundant in our world.

She writes stories of home, both the homes and kitchens she has inhabited and the natural world we share and that feeds us so well. “For what is home,” she asks in the introduction, “if not the first place where you learn what does (and does not) nourish you?”

Each brief entry in Bite by Bite focuses on a single food and opens with a full-color illustration from artist Fumi Mini Nakamura, drawings that Nezhukumatathil calls “magical and marvelous” in her acknowledgments. These lively pieces draw the reader in, but it is the words that bring each food to life. In most chapters, Nezhukumatathil blends memoir or personal reflection with historical or botanical information on each item, making unexpected connections along the way.

The first chapter, focused on the rambutan, pairs a story about her curly hair and an upcoming middle school dance with the description of this “fruit with the wildest curly spinterns radiating from its bright scarlet skin” before going on to describe the height and fruiting frequency of rambutan trees and the size of its drupe (“about the length of a double-A battery”).

Bouncing from these informative moments into reflection, Nezhukumatathil wrestles with her desire to have hair like the other girls her age, teased and sprayed despite her Filipina mother’s prohibition against hair products. Then she takes readers back to the first time she visited her grandmother in India and found that she had the same beautiful curly hair, “a dark waterfall across her back.” That realization didn’t change her feelings about her hair, at least not right away. It would be many more years before she could write these words: “Let the questions of what is beauty and what is not-beauty fruit down your back. I can’t bear (or more accurately, tolerate) anything less than the weight of the same waterfall from my grandmother.”

Bouncing from these informative moments into reflection, Nezhukumatathil wrestles with her desire to have hair like the other girls her age, teased and sprayed despite her Filipina mother’s prohibition against hair products. Then she takes readers back to the first time she visited her grandmother in India and found that she had the same beautiful curly hair, “a dark waterfall across her back.” That realization didn’t change her feelings about her hair, at least not right away. It would be many more years before she could write these words: “Let the questions of what is beauty and what is not-beauty fruit down your back. I can’t bear (or more accurately, tolerate) anything less than the weight of the same waterfall from my grandmother.”

Words such as “drupe,” “aril,” or “stolons” remind you that the author is a naturalist and also a poet, always in search of the perfect word. Sometimes she includes her poetry, as when she tries to describe the ineffable flavor of mangosteen: “like a poem with the word ghost in at least four different languages / a cage trap of lightning, a sheen of sugar in a bowl.”

At other times, her prose is just as poetic, as in the chapter describing a snowy day when she made gifts of homemade vanilla extract with her son: “Inside a little ranch house, a mother was teaching her son how to tie a bow of red-and-white baker’s twine for each gift tag. How to make something that wouldn’t stay yours, but would be a remembrance of the grace in slowing down and thinking of the future, of others’ happiness.”

The book is uneven in a few spots where the tenuous connections don’t hold, as in the chapter on apples that shifts jarringly to her heartsickness over mass shootings. Despite the occasional misstep, however, there is much to love in these pages. In the conclusion, she highlights her mother’s signature dessert: leche flan. Because it stands out in her memory, Nezhukumatathil wonders if her children or her guests will remember the times she tried to make something special for them. She concludes that they likely won’t recall the details, “but that’s not the point when it comes to loved ones. You heat up the waffle iron. You shave the ice. … You take the extra bit of time. It doesn’t always turn out how you think it should. You make it anyway.”

Bite by Bite proves the power of the extra steps taken, the intentional acts of caring and provision that live on in our memories long after the last bite.

Sara Beth West is a school librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.