Against Professional Southerners

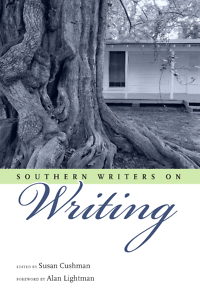

Southern Writers on Writing, a new essay collection edited by Susan Cushman, offers new answers to an old question

While making the media rounds after winning the 1962 National Book Award for his debut novel, The Moviegoer, Walker Percy was asked by more than one curious New York journalist why the South produces so many good writers. His pat response: “Because we lost the War.” Not long afterward, in an essay titled “The Regional Writer,” Flannery O’Connor expanded on Percy’s remark. “What he was saying was that we have had our Fall,” O’Connor wrote. “We have gone into the modern world with an inburnt knowledge of our human limitations and with a sense of mystery which could not have developed in our first state of innocence—as it has not sufficiently developed in the rest of the country.”

Despite having been answered again and again in manners both as curt as Percy’s and as thoughtful as O’Connor’s, the question persists, drenched as it is with inherent condescension. One suspects that a more honest query would sound something like this: “How could a region so reputedly backwards, anti-intellectual, bigoted, misogynistic, uneducated, and retrograde in its politics give the world the likes of Faulkner, O’Connor, Welty, and Percy, or, more recently, Donna Tartt, Tayari Jones, Percival Everett, Jesmyn Ward, and Tom Franklin?”

Nevertheless, we Southern writers take the bait every time. The only thing we love as much as telling stories is explaining where they come from. We bristle at the contempt our Northern compatriots express for our homeland and take pride in the solidarity of our ilk—never mind that the small hamlets of Mississippi are about as far in every imaginable way from the high rises of Atlanta as is Kansas from the Land of Oz.

The label “Southern Writer” is a mixed blessing indeed, though, as is the case with most blessings, better embraced or tolerated than denied. Southern Writers on Writing, a new anthology of essays edited by Susan Cushman, is not the first attempt to plumb the depths of what it means, as Faulkner wrote, to “tell about the South.” But it is distinguished by a division into helpful categories—”Becoming a Writer”; “Place, Politics, People”; “Writing About Race”—and the presence of diverse voices, from sage elders like Clyde Edgerton and Lee Smith to rising stars like Julie Cantrell, M.O. Walsh, and Michael Farris Smith.

Humor always plays well in writing about writing; the collection kicks off with an equally witty and soulful piece by Oxford, Mississippi, journalist, author, and raconteur Jim Dees, host of Thacker Mountain Radio Hour and a close friend of departed legends Willie Morris, Barry Hannah, and Larry Brown, among many others. “If you subtract Mississippi from American arts and letters, you’d still have hip hop and Stephen King, but America’s canon of arts would be much poorer,” Dees writes. “Who wants to live in a world without Elvis?”

Memphis native and Thurber Award winning humorist Harrison Scott Key explores the challenge of writing memoir with similar aplomb: “How do I map the expressionist strangeness of my inner life in a way that invites others to sit in the cockpit of my soul and soar through the atmosphere of me, which is the only me I’ve ever been and the only unique thing I possess anyway? And the answer: I don’t know. It’s hard. And the other answer: get over it.”

Memphis native and Thurber Award winning humorist Harrison Scott Key explores the challenge of writing memoir with similar aplomb: “How do I map the expressionist strangeness of my inner life in a way that invites others to sit in the cockpit of my soul and soar through the atmosphere of me, which is the only me I’ve ever been and the only unique thing I possess anyway? And the answer: I don’t know. It’s hard. And the other answer: get over it.”

Another distinguishing aspect of Southern Writers on Writing is a more than usually direct accounting of the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow in shaping the Southern canon and deferring the dreams of African-American writers whose voices have only recently begun to be acknowledged and still fight to be heard in a publishing climate historically dominated by white men.

“I’m often asked why Mississippi’s civil-rights past plays such a large role in my work as a writer and editor, particularly when what I am writing is focused on the present,” writes W. Ralph Eubanks. “With respect to whether it was painful to revisit the past, I pointedly asked the questioner, ‘for whom is it painful?’ Is it more painful for me to remember the violence that erupted all around Mississippi—violence directed at people of color like me—or is it more painful for those who listen to me tell these stories to be reminded of those who did little to stop those senseless and brutal acts?” This and other accountings of the dark side of Southern history make Southern Writers on Writing as essential as it is entertaining and insightful.

Of course, no accounting of Southern writing can spare us a fair share of sweet tea, bourbon, trees dripping with Spanish moss, and front-porch storytelling under a full moon on a hot summer night, but the writers who populate this neat, nimble anthology are rarely lacking in self-awareness. Katherine Clark puts it best, describing the advice of a former professor: “‘Please don’t turn into a professional southerner,’ he warned me. These are words to live by for anyone who aspires to be a Southern writer.”

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.