Alchemist of the American Roadside

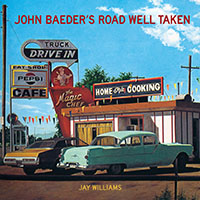

John Baeder’s Road Well Taken remembers the great American road trip of one of our most iconic painters

Artist John Baeder once said of American roadside diners, “I saw them as temples from a lost civilization, not just as restaurants where you’d grab a nibble.” To Baeder, American diners were shrines of a disappearing landscape, symbolic of the hearth, the provider, and the community. In John Baeder’s Road Well Taken, Jay Williams presents a comprehensive account of Baeder’s career, his inspiration, and his inner life. Williams, Curator of Exhibitions and Collections at Vero Beach Museum of Art, organized Baeder’s recent four-museum retrospective, and his book seems the crowning achievement of their work together.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Baeder lived in a Mad Men set. As creative director of a New York advertising firm, he understood that humans shape their identities through the social and personal meanings of objects. This understanding led him to capture the spirit of what he called the “sacred small town.” Early on, Baeder began to collect linen-finish color postcards of roadside attractions. They were hyper realized and touched-up, prioritizing sleek lines and bright colors. Curiosity led him to blow up these miniatures into paintings, omitting details and prioritizing the subject. The result was somewhat hyperrealist in style, but unlike the hyperrealists of the age, Baeder took a humanistic approach, magnifying relationships through the rendering of Americana relics and preserving the spirit of a bygone era.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Baeder lived in a Mad Men set. As creative director of a New York advertising firm, he understood that humans shape their identities through the social and personal meanings of objects. This understanding led him to capture the spirit of what he called the “sacred small town.” Early on, Baeder began to collect linen-finish color postcards of roadside attractions. They were hyper realized and touched-up, prioritizing sleek lines and bright colors. Curiosity led him to blow up these miniatures into paintings, omitting details and prioritizing the subject. The result was somewhat hyperrealist in style, but unlike the hyperrealists of the age, Baeder took a humanistic approach, magnifying relationships through the rendering of Americana relics and preserving the spirit of a bygone era.

Williams aligns the story of John Baeder with social and economic history. Baeder’s early photographs of urban renewal in Atlanta showed the encroachment of city planning on small businesses. He relied on a landscape’s man-made shapes—bricks, wood siding, and cement blocks—to anchor his compositions, always attentive to signage that juxtaposed conditions. In developing this style, Baeder looked to the work of Farm Security Administration photographers, who traveled the country during the Great Depression to document rural poverty.

As Williams notes, Baeder continued to seek out pockets of landscape that resist “progress,” and he found them on the open road. His interest in diners pays homage to middle-class and blue-collar culture. Like other postmodernists working at the time, Baeder questioned the precedent of “high art” by elevating the commonplace to significance. Gas stations, hand-painted signs, mom-and-pop eateries, and taco trucks make up Baeder’s landscape. He viewed his work as a way to preserve these businesses before they were shuttered; in fact, he began to talk about “diner-consciousness” as a way to preserve not only buildings but also a way of life after World War II.

In the post-war economy, cars became part of our national identity. Middle-class folks could own one, or even two, and thousands of roadside resting stops sprang up to meet a new need. Williams writes, “The Great American Road Trip of those years can be seen as a secular pilgrimage to find the American dream.” For Baeder, this pilgrimage was literal: he drove thousands of miles, seeking out diners around the country to photograph and paint. But he also sought something else. He didn’t merely pull his car up and snap some photos from the parking lot. He entered the diners, talked to the waitresses, met the owners, and surely ate a lot of pancakes. Baeder’s work thus becomes not just an homage to landscape but a tribute, sanctifying American community and national aspirations. “In a sense, diners and mom-and-pop motels were like the medieval hostels where pilgrims could find a meal and a place to sleep on the way to an exalted destination,” Williams writes.

In the post-war economy, cars became part of our national identity. Middle-class folks could own one, or even two, and thousands of roadside resting stops sprang up to meet a new need. Williams writes, “The Great American Road Trip of those years can be seen as a secular pilgrimage to find the American dream.” For Baeder, this pilgrimage was literal: he drove thousands of miles, seeking out diners around the country to photograph and paint. But he also sought something else. He didn’t merely pull his car up and snap some photos from the parking lot. He entered the diners, talked to the waitresses, met the owners, and surely ate a lot of pancakes. Baeder’s work thus becomes not just an homage to landscape but a tribute, sanctifying American community and national aspirations. “In a sense, diners and mom-and-pop motels were like the medieval hostels where pilgrims could find a meal and a place to sleep on the way to an exalted destination,” Williams writes.

Williams’s prose is readable and familiar and, at times, brightly poetic. The book’s great strength is in its succinct descriptions of individual paintings. Perhaps “descriptions” is not quite accurate, for Williams courts each painting, carefully examining its hues, textures, and lines to convey its specific voice. Of Diner Door (1974) Williams writes, “Unique in Baeder’s production, this watercolor is an open declaration of his love for the unity of ‘materials and textures of colors’ in his favorite subject matter, with color dominating the whole.” Like any fine writer, Williams does the difficult work of showing us why we must appreciate Baeder. By walking us through his own interpretation, we learn how to read the paintings as well as gain facility in thinking and talking about art in general.

In addition to countless hours of interviews with Baeder, Williams draws from conversations with curators, friends, artists, and arts administrators. He cites philosophers and critics, historians and psychologists in this exhaustive attempt to illuminate Baeder’s life and work. The text is illustrated with nearly 300 full- and half-page prints of Baeder’s work spanning more than forty years. Williams devotes chapters to still-life and classic-aircraft paintings, in addition to Baeder’s well-known roadside work. Readers will learn about the artist’s predilection for Jungian philosophy, his move to Nashville in 1980 (“It’s magical, spiritual, and soft,” he said), and his successful forays into book publishing.

For Williams, John Baeder is an alchemist, transforming everyday matter into gold. John Baeder’s Road Well Taken gives readers access to the artist’s work and history but also to the rich inner life that infused his paintings with mysticism.

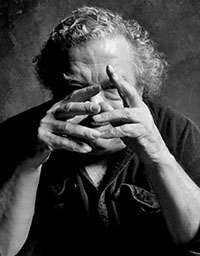

Erica Ciccaroneis an independent writer living in Nashville, Tennessee. She holds an M.F.A. from the New School and is a regular contributor to several regional arts magazines.