An Oak Ridge Story

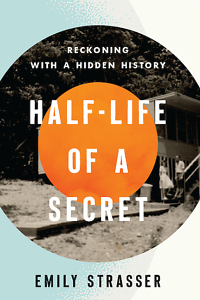

Half-Life of a Secret explores a family’s secrets and a nation’s silence

On the opening page of Emily Strasser’s Half-Life of a Secret: Reckoning with a Hidden History, she describes lying beneath flowered sheets in the safety of her grandmother’s house near Oak Ridge, transfixed by a photograph of her long-dead grandfather standing in front of a nuclear explosion.

“I felt myself floating, unmoored from time and space, drawn by my grandfather’s eyes, eyes that knew everything yet said nothing,” she writes of her childhood memory. Behind her grandfather, “fire blossomed in silence.”

A blend of memoir and historical investigation, Strasser’s book explores what her grandfather, who died before her birth, must have seen with those eyes, what lay behind that silence. An outsider as an intellectual growing up in a large farm family, George Strasser had made his way up the ladder working as a chemist on Oak Ridge’s secret Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. Meanwhile, he struggled with personal secrets: his mother’s suicide and his own alcoholism and mental illness. For Strasser, family secrets are intertwined with national ones.

Her research is exhaustive. Delving into government archives and family memorabilia, supplemented by interviews and personal visits, she puts the family story in the context of a nation at war. Like most newcomers to the “secret city,” Strasser’s grandparents knew little of Oak Ridge’s true purpose when they moved there in the early 1940s. The city was new. The Army Corps of Engineers had chosen the site because it offered, as one architect she interviewed put it, “a kind of clean, uncluttered, uncommitted area with nothing to stand in the way of an ideal plan.” Once the poor farmers, sharecroppers, and Native people who had long called the area home were evicted, the government put up “a series of homely little American villages” for the thousands of workers it would need to employ for bomb building. For the Strassers and others like them, it meant “something new and better.”

Of course, “new and better” sounds cold at first. How could a workforce of thousands unknowingly build a bomb capable of mass destruction? But wartime Americans, carefully vetted for patriotism, pledged to reveal nothing, to see nothing. When asked by outsiders, “What are you making out there?” Oak Ridgers learned playful, evasive answers. “Eighty cents an hour,” they might quip, proud to make twice the minimum wage. Asked “How many people are working out there?” they might jest, “Oh, I guess about half of them.” Colleen, a former “leak test operator” whom Strasser interviewed, said, “We were so stupid we didn’t know anything else. Isn’t that crazy? We were programmed for doing that.”

Of course, “new and better” sounds cold at first. How could a workforce of thousands unknowingly build a bomb capable of mass destruction? But wartime Americans, carefully vetted for patriotism, pledged to reveal nothing, to see nothing. When asked by outsiders, “What are you making out there?” Oak Ridgers learned playful, evasive answers. “Eighty cents an hour,” they might quip, proud to make twice the minimum wage. Asked “How many people are working out there?” they might jest, “Oh, I guess about half of them.” Colleen, a former “leak test operator” whom Strasser interviewed, said, “We were so stupid we didn’t know anything else. Isn’t that crazy? We were programmed for doing that.”

At home, George Strasser raised a picture-perfect family and earned good money in a profession he’d trained hard for, but he struggled with demons not fully understood. With mental health stigmatized, the nature of his suffering was often coded on records his granddaughter examined. His mother’s suicide was such a carefully guarded secret that few family members knew about it. George was in his teens when she left the house one morning to feed the chickens, as usual. Chickens fed, she continued on to the barn, where she hanged herself. George and his brother, working nearby, found her.

One of George’s Manhattan Project coworkers clued Strasser in to the fact that George, too, may have wanted to kill himself. She wonders if hearing news of the Hiroshima bombing on August 6, 1945 — learning for the first time what he’d been doing — worsened an inherited illness.

Near the end of the book, Strasser describes visiting Hiroshima, where she meets several hibakusha, or bomb survivors. They were surprisingly kind. “It was not him, but war,” one woman replied when Strasser told her about George. In a museum displaying items such as the skin and nails stripped by the bomb from the body of a junior high student, she noticed the Hiroshima story was framed in passive voice: “The bomb was dropped.” It surprised her. “Here, there was no war. No American planes or American flight crews or American generals picking out Japanese targets on maps in war rooms.” Nor, apparently, was there mention of Pearl Harbor, as Americans from the WWII generation might expect. Was peace, Strasser wondered, “all about soothing our consciences, writing a history in which no one was responsible?”

As we approach the 80th anniversary of the Japanese bombings, Half-Life of a Secret offers an important way to rethink a critical moment in global history. That moment’s residue remains not only in collective memory but, according to scientists, in the air and water and soil around Oak Ridge. As a granddaughter, Emily Strasser grapples with how her grandfather’s work implicates her. “The comfort of my life is founded on the nuclear weapons industry,” she writes. “What I see in my childhood, in my family, is just a magnification of what I see in Oak Ridge, in the nation at large.”

In that photo of George, she remembers the fireball. It “could have been the end of the world or the beginning.”

Jane Marcellus is a writer whose published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism. Her work was listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020. She is a former professor at Middle Tennessee State University.