Arcs of Hope and Tragedy

Frye Gaillard delivers a sprawling, panoramic history of the 1960s

This interview was originally published on August 2, 2018. The post has been updated with new publication details.

***

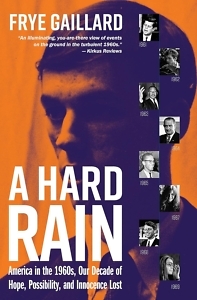

Frye Gaillard’s A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s, Our Decade of Hope, Possibility, and Innocence Lost is an expansive history of the 1960s, full of big conflicts and quiet moments, tracing an arc of liberal idealism and disillusion. It captures the experiences of many young people from that generation—including Gaillard himself.

Gaillard is the writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama. A longtime journalist, he has written extensively on Southern race relations, politics, and culture. Gaillard has written or edited more than twenty-five books, including Watermelon Wine: The Spirit of Country Music and Prophet from Plains: Jimmy Carter and His Legacy. Prior to his appearance at the 2018 Southern Festival of Books, he answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Gaillard is the writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama. A longtime journalist, he has written extensively on Southern race relations, politics, and culture. Gaillard has written or edited more than twenty-five books, including Watermelon Wine: The Spirit of Country Music and Prophet from Plains: Jimmy Carter and His Legacy. Prior to his appearance at the 2018 Southern Festival of Books, he answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: At various points throughout the book, you write about your personal memories. What happened in your 1960s? How did those experiences shape A Hard Rain?

Frye Gaillard: I was thirteen when the 1960s began, listening to rock ‘n’ roll, playing sports, cheering for Alabama football, but it slowly dawned on me that these were exciting times beyond my immediate, teenaged frame of reference. I watched President Kennedy’s inauguration on TV in my junior-high-school homeroom, watched the horrifying coverage of his assassination when I was in high school. In 1963, as a high-school junior, I witnessed in person the arrest of Martin Luther King Jr. in Birmingham, and during my college years, 1964-68, I became, like so many of my peers, caught up in the great story arcs of tragedy and hope that defined the decade. I was drawn to the great men and women who embodied our hopes, and grieved in a way that has never quite stopped when some of them were murdered.

Chapter 16: The book reflects a great admiration for the activists of the civil-rights movement. How did they shape the trajectory of the 1960s?

Gaillard: When I witnessed the arrest of Dr. King, close enough to where I was standing that I could see the sadness in his eyes, the civil-rights movement for me suddenly had a face. I was awed by the courage of young people who seemed to embody a hope that America would become an even better place, that the ideals of our founding would become more fully realized. That idealism was, in many ways, the very heart of the decade, but there were parallel story lines that were darker—war, disillusionment, assassination, despair.

Chapter 16: The subtitle refers to an “innocence lost.” What was that innocence? How did we lose it?

Gaillard: As the Vietnam War gained momentum and the resistance against it grew strong, and then bitter, and as the restlessness and rage of Black America exploded in the form of urban riots, there were men (some women too, but men were more celebrated at the time) like Dr. King and Robert Kennedy who refused to bend to the forces of violence and despair, but who also continued to speak for the dispossessed with a passion we have seldom seen in American politics. Many of us clung to their example, their belief that our divisions could be healed, and then suddenly they were gone, felled by assassins’ bullets just as President Kennedy had been.

Gaillard: As the Vietnam War gained momentum and the resistance against it grew strong, and then bitter, and as the restlessness and rage of Black America exploded in the form of urban riots, there were men (some women too, but men were more celebrated at the time) like Dr. King and Robert Kennedy who refused to bend to the forces of violence and despair, but who also continued to speak for the dispossessed with a passion we have seldom seen in American politics. Many of us clung to their example, their belief that our divisions could be healed, and then suddenly they were gone, felled by assassins’ bullets just as President Kennedy had been.

I think that in the late-1960s America lost the innocent certainty that we were both great and good, and a new kind of politician emerged who sought to exploit rather than heal our divisions. George Wallace did it with a populist fervor, and Richard Nixon with a kind of cold cynicism that only grew stronger in the years to come. For me, both the idealism of the 1960s and the innocence we lost in those times have continued to echo down through the years and have shaped the politics of the twenty-first century.

Chapter 16: As befitting a book with a title referencing a Bob Dylan song, we meet many musicians: Sam Cooke and Patsy Cline, the Beatles and the Beach Boys, Linda Ronstadt and Jimi Hendrix. What can music tell us about American life in the 1960s?

Gaillard: I have always seen music as a valuable window on our history and culture and have written about it that way through the years. I am not a musician, but I have always loved the music I grew up with—rock ‘n’ roll, folk-protest, rhythm and blues, country. Some of it was simply joyful escape, like Motown or the early Beatles, but there were also the performers like Dylan, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Johnny Cash—or Sam Cooke with his iconic “A Change Is Gonna Come”—whose lyrics made us think and embodied our disillusionments and hopes in a way that was profound.

As the women’s movement gained momentum in the 1960s, I thought it was no accident that there were important artists who projected feminine strength, like Linda Ronstadt, Patsy Cline, or Janis Joplin. Or Odetta and Nina Simone. Or Aretha Franklin and Loretta Lynn. In 1969, as the decade came to an end, I was moved by the fact that Elvis Presley would record “In the Ghetto,” a song of empathy written by country singer Mac Davis about life in inner city Chicago.

Johnny Cash’s network television show in that same year sought to heal our divisions through music by reaching out to country and folk audiences simultaneously, people with different political perspectives. And of course there was Woodstock, a communal celebration ending with Hendrix playing that stunning electric-guitar solo of “The Stars Spangled Banner.”

Chapter 16: In the course of your research, what stories most surprised you? What did you learn that you did not know?

Gaillard: I came across tidbits that I had forgotten, like the fact that homosexuality, or at least the homosexual act, was illegal in every single state when the decade began. Illinois was the first to change that. I had forgotten that the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire and gave momentum to an environmental movement, which was spearheaded by a U.S. Senator named Gaylord Nelson, who came up with the idea of Earth Day. I did not know that President Kennedy had endorsed the controversial environmental writings of Rachel Carson, or that he had chosen former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to chair a Commission on the Status of Women, which gave momentum to an emerging wave of feminism. I did not know that Betty Friedan had scratched out the founding principles for the National Organization for Women on a napkin. And I certainly did not know that in Chicago in 1969 a Black Panther — whose name, I kid you not, was Robert E. Lee — made common cause with a group of alienated white guys from Appalachia whose symbol was the Confederate flag. There was no shortage of surprises.

Chapter 16: What can the 1960s explain about American politics and culture today? What lessons should we learn?

Gaillard: I think in many ways the sixties live on. The seeds of our troubled times were sown at least partially in those days. Others with different perspectives will disagree, but Barack Obama’s election in 2008 represented a fulfillment of our greatest hopes-a brilliant young black man chosen to lead our country. In the 1960s, we could barely imagine such a thing, but we were swept up in intoxicating notions of racial equality.

The backlash against Obama, culminating in Donald Trump, more than fulfills our greatest disillusionments as the 1960s came to a close. Unlike Trump, George Wallace did not have Fox News as a megaphone for his politics of rage, and now I worry that our national resentments are more powerful than our urge to come together. There is no Robert Kennedy today giving singular voice to that hope, or at least none that I can see. But we do see the kids from Parkland, Florida, and hear the voices insisting that Black Lives Matter, or those of women with the simple, powerful words “Me Too.” So I think maybe there is hope after all. But as in the 1960s, there is still the struggle between our better angels and their opposite.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.