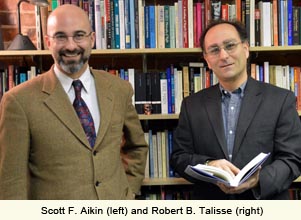

Arguing For Democracy

Vanderbilt philosophers Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse discuss their handbook for political disagreement

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: In conjunction with Humanities Tennessee’s exhibition tour of Voices and Votes: Democracy in America, Chapter 16 is revisiting coverage of notable books on civil rights and the foundations of a democratic society. This interview originally appeared on February 7, 2014.

***

Winston Churchill once claimed that the best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter. According to Vanderbilt philosophy professors Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse, it doesn’t have to be that way. While granting the current abysmal state of political deliberation among professionals and laypersons alike, they maintain that proper argument is fundamental to both cognitive and democratic health. In Why We Argue (and How We Should), Aikin and Talisse set ground rules for productive democratic disagreement.

“Democracy is the social and political manifestation of our individual aspiration to manage our cognitive lives according to reasons,” they write. The failings of contemporary democracy, it follows, can be traced to our inability to engage appropriately in political debate. By wallowing in a host of dialectical fallacies—most of which paint the opposition as stupid, out of touch, or worse––contemporary political debate quickly devolves into distraction and distortion, leaving the fruit of democratic compromise to rot on the tree. The solution, say Aikin and Talisse, can be found in reasonable public debate. Only by addressing our opponent’s reasons, as opposed to our opponent herself, and by giving a proper hearing to those reasons can we foster the reciprocity upon which democracy depends.

Aiken and Talisse recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Aiken and Talisse recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: You make the case that democracy and reasoned argument are inseparable. In a democracy, are people who vote according to their heart a liability?

Talisse: It all depends on what precisely is meant by “voting with your heart.” You’re correct that Scott and I argue that democracy is the political manifestation of the basic aspiration to be rational; in short, democracy provides the social and political background necessary for pursuing our rational aims. The most basic aim that we have is to believe what is true and reject what is false. But it turns out that we can pursue that aim only within a social and political environment that enables us to believe on the basis of our best reasons. In order to base our beliefs on good reasons, each of us needs access to reliable sources of information, data, and evidence. Additionally, we need more: we need to deal rationally with disagreement; we need to manage conflicts among rational creatures. And this means that we need to argue well in order to pursue our most basic aspirations.

In Why We Argue (And How We Should), Scott and I argue that we need a democratic society in order to be rational as individuals. But, as your question reveals, there’s the rub. In a democratic society, citizens may participate, and even vote, in almost any way they choose. So whereas a democratic society enables us to be rational, it also allows for a lot of bigotry, bias, and blind passion. However, notice that the blindly passionate do not take themselves to be blind. They take their passion to be well warranted by their reasons.

An interesting feature of the kind of question that you raise is that the reason-versus-passion concern typically comes from people who see themselves on reason’s side of the matter. That is, those who talk about people who “vote with their hearts,” are often talking about other people rather than themselves. We all see ourselves as voting with our heads, and not with our hearts, or at least not blindly with our hearts.

Now for a second point. We need democracy in order to be rational, but this is not to say that rationality is cold, calm, detached, and passionless. In fact, in Why We Argue (And How We Should), Scott and I show that proper argument can be emotional, loud, heated, and even in some ways impolite. That is, proper argument is not opposed to impassioned commitment. So, to answer your question, those who vote according to their heart are no liability as such. The liability lies in voting in ways that are insensitive to reasons and arguments––and one can project a good deal of calm, cool reasonableness while still being irrationally stubborn. The real threat to democracy comes from those who have a disregard for the reasons and arguments offered by their political opponents, those who are cocksure and dogmatic, those who believe that their political opponents are ipso facto stupid, ignorant, benighted, or treasonous.

Chapter 16: If true democracy thrives in the dialectic between opposing views, how do you account for the fact that political compromise so frequently leads to a middle ground where nobody gets what they want?

Aikin: Compromises wherein nobody gets what they want are certainly a bad deal, and that might have to do with the fact that the middle isn’t always where things should end up. First, not all dialectical exchanges have to proceed on the thought that we’re looking to meet in the middle. It’s distinctly possible for one side to be just plain wrong and have to evacuate their entire position. The point of the dialectical setup is to identify places where the disagreeing sides have agreement and what’s defensible about the two sides. This, of course, isn’t just a matter of assessing your opponent, but it’s also a matter of taking that same critical view to your own side––knowing and being honest about what’s well supported and what’s not.

I think also that there’s a strange phenomenon of buyer’s remorse with compromises. You always, in hindsight, compare the compromise outcome with what you’d hoped for coming in to the discussion––namely, getting everything you wanted. For sure, you’re going to think that compromises, from the perspective of that comparison, are not good outcomes. But that’s not the right comparison set––you’ve also got to consider the other alternatives, too. Compare it with the other side getting everything they want, and you nothing. Or compare it with no compromise at all and nothing getting done. It’s clear that compromises aren’t the first choice, but they, given the alternatives, are the best.

What’s important is that good argument can make it clear what’s worth compromising over and what’s not––it makes it clear where your opponents, and where you, are coming from. The phenomenon of bad compromises often arises because of bad argument. Robert and I have been very worried about the regular thought that one’s political opponents are vicious, hateful, and beyond reason. For sure, if you have that view of your opposition, you’re not going to be able to argue with them, and any compromise with them is a terrible idea. But the world is a complicated place, and people’s motives are more nuanced than that of sheer greed and the desire to destroy the country. If we can, with fellow citizens, start with the thought that we’re trying to promote the common good (but we disagree about the means to promote it), then our compromises will start looking a lot more appropriate.

What’s important is that good argument can make it clear what’s worth compromising over and what’s not––it makes it clear where your opponents, and where you, are coming from. The phenomenon of bad compromises often arises because of bad argument. Robert and I have been very worried about the regular thought that one’s political opponents are vicious, hateful, and beyond reason. For sure, if you have that view of your opposition, you’re not going to be able to argue with them, and any compromise with them is a terrible idea. But the world is a complicated place, and people’s motives are more nuanced than that of sheer greed and the desire to destroy the country. If we can, with fellow citizens, start with the thought that we’re trying to promote the common good (but we disagree about the means to promote it), then our compromises will start looking a lot more appropriate.

Chapter 16: You clearly believe that polarization leads to false views. I’m wondering, though, is it possible for a group with extreme views to be argumentatively responsible?

Talisse: There is a distinction to be made here. There are two senses of “polarization.” Sometimes, we use “polarization” to denote a situation in which the distance between opposing sides is so great that there is no common ground between them, and thus no basis for compromise, or even dialogue. Polarization in that sense is surely a problem in a democracy, as it leads to governmental deadlock and paralysis. But there’s another sense of the term, and this is the sense that Scott and I are most interested in. There is a well-studied and documented phenomenon called “group polarization.” Polarization in this sense does not describe the intellectual distance between one person’s belief and her opponent’s; rather, it describes the way in which an individual’s belief changes or shifts when that individual surrounds himself only with like-minded others.

The thought is simple: let’s say that Ann is generally pro-choice, but sees the need for some strict legal regulations concerning access for women under eighteen. If Ann spends a few days talking about her views on abortion only with others who are pro-choice, her position predictably will begin to shift, imperceptibly to Ann, to one that recognizes less of a need for those legal restrictions. So too with the entire group of advocated various pro-choice views: as they talk only amongst themselves, the median view of the group will shift in the direction of a more extreme pro-choice viewpoint; it “polarizes” in the sense of moving towards the most extreme version of the kind of view the group began with. The phenomenon is found across the political spectrum, and it seems that differences in education, wealth, gender, and geography do not affect the tendency. Now, the crucial feature of group polarization phenomenon is that the belief-shift is not occasioned by reasons and argument; rather, the polarization is fueled simply by group dynamics. And that’s the worrisome feature.

You are of course correct that those who hold views that might be regarded as “extreme” can be argumentatively virtuous; indeed, extreme views can even be correct! Again, the polarization worry concerns the grounds upon which individuals hold their beliefs. The lesson is that those who insulate themselves from having to consider opposing views are losing control over their own minds. Scott and I sometimes get the following kind of response: “Argument and reasoning is all fine and good when you don’t know the truth. But once you have the truth, there’s simply no point in talking to those with whom you disagree––you know the truth, and those who disagree are simply wrong. So why bother even talking to them?” The group polarization phenomenon shows that this thought is deeply and tragically mistaken. Insulating oneself from opposition is a surefire way to lose the truth.

Chapter 16: Democratic revolutions––In France and America, for example, and more recently in Romania and Nepal––seem to be necessarily extremist in nature, requiring a wholesale rejection of the other’s values that’s anything but a dialectic approach. In your view is revolution actually antithetical to a rational democracy?

Talisse: There is a lot to be said here, but the short answer is yes. Revolution is justifiable only where there’s no democracy, or a democracy in name only. And revolution is justified only when it aims not only at ousting a tyrannical power but also at establishing democratic rule. The stated reasons supporting the great democratic revolutions in history are aimed at demonstrating the absence of democracy and the need to establish one.

Now, of course, a lot of “democracy” talk among revolutionaries is just talk, mere PR, and it’s notoriously difficult, especially in the short-run, to determine whether any particular revolution is in fact justified. And it is similarly difficult to distinguish between a democratic society that is seriously failing at democracy and a despotic society that claims to be a democracy. Again, revolution against despots is justifiable. Yet the question of what citizens may do to effect far-reaching social change in the direction of democracy when their democratic society is badly failing at democracy is complex and very difficult––but it’s also why we still read people like Thoreau, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X on these issues.

But if we take the simple case of a democratic uprising against a brutal dictator, you’re right to say that the revolution is premised upon an outright rejection of the standing regime’s values. Scott and I embrace that. Our view is that in a democracy, we must engage in argument with our political opponents. This is to presume that our opponents are our fellow democratic citizens, citizens with whom we may disagree deeply but who nonetheless share a common underlying commitment to a basic democratic and constitutional order. The worry that Scott and I see––and this is part of our motivation in writing Why We Argue (And How We Should)––is that our current political climate encourages citizens to hold those with whom they politically disagree in contempt.

The thought seems to be that reasoned and responsible political disagreement is impossible, as there could be only one reasoned and responsible political viewpoint. The tale is told simply by looking at the titles of books of popular political commentary: Liberalism is a Mental Disorder; The Republican Noise Machine; If Democrats Had Any Brains, They’d be Republicans; The Republican War on Science; and so on. The common message in popular political discourse is that those who disagree with your views are therefore stupid, blind, or worse. That is a dangerous and profoundly anti-democratic message. And yet it’s the unifying lifeblood of the billion-dollar industry of popular political commentary.

Chapter 16: What would you say to that segment of society who are done with politics? Life is short, I hear them say, and they don’t want to spend it playing someone else’s rigged game.

Aikin: My first response is that I very often share the malaise. Attending to politics, and especially to the rhetorical overload, spin, and general hatefulness of so much of it, is exhausting and saddening. Robert and I regularly despair at the state of our current political discourse, and it’s a very tempting thought that we can just quit paying attention and let it all go to hell.

Notice first, that this temptation is based on exactly the kind of thoughts we’ve argued for––good politics is about the fair exchange of reasons, with the objective of promoting the common good. And so when we despair over the fact that the game is rigged and are tempted to give up, that’s evidence that the view that Robert and I have been arguing for (that politics should be properly run argument) is right––just that we’re not doing it well. So our shared frustration with politics as it is practiced bespeaks the deep rational norms of politics. Every cynic has an idealist’s heart.

Second, notice something about the temptation to turn one’s back on politics, to ignore it and let it all go its own way. Only a very privileged few can realistically take that attitude. For many people, how the discussions go will drastically change their lives for better or worse. If it’s possible for someone to say: I don’t care about politics because it’s all a rigged game; I don’t pay attention anymore, that person has a privilege of being immune to the consequences of the discussions. How can you get that kind of privilege? The short answer: by having the game rigged in your favor more often than not. As a consequence, checking out of political discussion because it’s proceeding in an ugly fashion is really a form of complicity with the rigging and injustice of the system.

So, yes, by all means, people should experience the distastefulness of ugly political exchange and feel the temptation to check out. That bespeaks a healthy mind. But the matter is that of overcoming that temptation to check out and staying plugged in, keeping the discussion going, and being vigilant about justice. It’s a tough job, but democracy is work.

Chapter 16: You admit that your views are often met with charges of ivory-tower naiveté, but you also clearly believe that even in a rational democracy people have to get their hands dirty. How would you go about the process of educating the American populace in the ways of proper argumentation?

Talisse: It is true that we are often charged with that kind of naiveté distinctive of academics. But the charge puzzles us. Our account of the place of reasoning in our cognitive lives draws nearly exclusively from what people in fact already do. Scott and I say that arguing well matters, and we say that because people act as if they think that it matters.

Nearly all political news these days is presented in a discussion/debate forum. Why is that? Scott and I say it’s because people generally think that it’s important to see the reasoning behind the political positions that people hold, and important to see how proponents of different views can respond to criticisms. Our Presidential campaigns are driven by debates. Why? Scott and I say it’s because people think that reasoning matters. Our news media is constantly describing itself in terms that extol the cognitive virtues of reason: the no spin zone; fairness; balance; straight-talk; trust; clearness; independence; and so on.

Why all this appeal to familiar cognitive virtues associated with rationality? Again, because reasons, evidence, debate, and argument aren’t simply the concerns of academics; arguing well is an aim of cognitive beings as such. So, importantly, in Why We Argue (And How We Should), Scott and I do not seek to impose some highbrow and anemic model of argumentation upon the everyday conversations of the ordinary folk. We’re not lecturing people on argument in that way. Instead, we are showing our readers the conception of argument that they already endorse and then trying to reveal the ways in which we can fall short of that standard of good argument.

In fact, much of Why We Argue (And How We Should) is devoted to identifying a series of argumentative mimics, bits of counterfeit reasoning that are difficult to distinguish from the real thing. But this, again, is not a matter of imposing an academic’s standard on ordinary efforts of reasoning. So, Scott and I begin with non-academic practices and attitudes about argument, draw out from these a conception of proper argument, and then attempt to examine the hazards we all encounter in trying to live up to them. That doesn’t seem to us like an ivory-tower enterprise.

Aikin: Let me follow up about our commitments beyond the book. We both teach logic classes and do a good deal of outreach beyond the academy representing the argumentative skills we value. Almost every person Robert and I have talked to about the book makes the same joke: Logic and politics? Good luck! But, immediately after making the joke, they welcome our attempt at fixing the problem. The thing is that, again, we are philosophy professors, and we’ve got the academic model of addressing problems, which is: write a book, and then talk about the book. The reality is that there’s a good bit of frustration with the quality and tenor of our national conversation, not only in politics but also about religion and morals, and Robert and I think that there’s a hunger for a better model. The book’s the beginning, and hopefully what follows is a better model for discussion.

Education is key, we think. To argue well, you’ve got to not only have some skills, but you’ve got to know a lot of facts. You’ve got to be scientifically literate, knowledgeable about the history of the debates, familiar with the kind of arguments your opponents give, and aware of drawbacks to your view. You’ve got to know things about our government; you’ve got to be culturally literate.

That’s a lot of overhead, and one thing we think that contributes to the failure of good discourse is the fracturing of culture. There’s little shared knowledge. In fact, it’s a feedback loop––the more fractured a culture, the more dissonant the political discourse, which leads to further cultural retrenchments. One of the reasons why conservatives and liberals don’t think that they can talk to the other side is that they never actually try. And that’s because they have very little they think they can talk about besides what divides them. And so the various sides have little more than caricatures of each other. The upshot is that the more you know about the history of issues you care about, the better you’ll be able to argue about political issues––you’ll know the governmental institutions and their roles, you’ll know about how the sides changed their minds, made compromises, you’ll know your own views better.