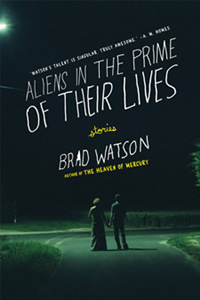

Author in the Prime of His Life

Brad Watson, who just won a Guggenheim, has come a long way from driving a garbage truck

To be a fiction writer from Mississippi is to inherit a literary legacy as heavy as Gulf Coast air in August, one rippling with stories of lives both remarkable and remarkably debauched. Young writers either embrace that legacy or reject it, but readers tend to hope for evidence that this literary mantle is a not merely a thing of the past, that Mississippi still produces a certain caliber and stripe of literary personality. Enter the Meridian-bred novelist and short-story writer Brad Watson, whose own story does not disappoint.

Growing up in a middle-class home where books were far from prized possessions, Watson was, by his own admission, mostly oblivious to the literary lions of his home state. During his junior year of high school, he married and had a child; after graduation, he set out for Hollywood with his young family in tow. When the acting dream didn’t work out, he found work driving a garbage truck.

Later, back in Mississippi, Watson enrolled in junior college, where he read Faulkner for the first time and discovered his calling. From that point, Watson’s literary star has been slowly, surely ascendant, as he’s traveled through the academic channels (a bachelor’s degree in English, an M.F.A. from the University of Alabama) to become a professor of creative writing and a critically lauded author. Watson’s books, one after the next, have snagged or been nominated for top-tier literary awards: his debut collection of short stories, Last Days of the Dog-Men, won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. A second book, the novel The Heaven of Mercury, was a finalist for the National Book Award. And his newest story collection, Aliens in the Prime of Our Lives, was a PEN/Faulkner Award finalist. Earlier this month, Watson received a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, one of the most prestigious and competitive literary awards in the country.

Watson’s fiction does not traffic in what his friend Barry Hannah dismissed as “a canned dream of the South,” but it is laced with just enough distinctly Southern settings and characters for a reader to feel she’s getting the real deal—a Mississippi writer who is carrying on the literary legacy of his home state. There is abundant summer heat; there are tragic, hard-bitten characters; there are “long, steamy corridor[s] of leaves” that lead to the coast. And there is ample humor providing ballast against sorrow.

Watson’s fiction does not traffic in what his friend Barry Hannah dismissed as “a canned dream of the South,” but it is laced with just enough distinctly Southern settings and characters for a reader to feel she’s getting the real deal—a Mississippi writer who is carrying on the literary legacy of his home state. There is abundant summer heat; there are tragic, hard-bitten characters; there are “long, steamy corridor[s] of leaves” that lead to the coast. And there is ample humor providing ballast against sorrow.

In advance of his public appearance at Nashville’s Montgomery Bell Academy on April 25, Watson answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: Dogs, swimming pools, cheap motels, and babies (both born and in utero): these all show up repeatedly in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives. What is it, for you, about these particular objects or images that make them resonate?

Watson: I like most dogs, and love some, especially my own (as it is with most people and children, as well). I hate all swimming pools except saltwater pools, because of the chlorine—feels like you’re bathing in bleach. I’ve spent far, far too many nights in cheap motels for one reason or another and if I could avoid it forever more I would, but I know that I can’t. I’ve been father to two babies, now older of course, and being a father—married or divorced—has been one of the most interesting, loving, and terrifying experiences in my life. So, of course, I write about it.

Chapter 16: In “Water Dog God,” the strange, wild, almost otherwordly quality of Maeve, and the sense of rural, isolated place and voice, made for a story that I could almost smell it was so rich. Can you explain a bit about how this story came about?

Watson: I wrote “Water Dog God” while I was trying to write an earlier story, “A Blessing” (in Last Days of The Dog-Men). It wasn’t going well, so I changed the point of view from third person (a young pregnant woman) to first person (a man living alone in a heavily wooded area on a river in rural Alabama) and tried to rewrite it that way. But I ended up writing an entirely different story with nothing surviving but the setting and a (different sort of) drowning.

I put the first-person “revision” away and forgot about it for a few years, then read it again and realized it was pretty good, revised it (this time without changing point of view or any other major elements), published it in The Oxford American, Best American Mystery Stories, and finally in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives. I like what you say about the texture of the story or the prose because one thing that changed in the recasting of the story was that the narrator/main character now was of this place, whereas in “A Blessing” the main character was just a visitor to it. She would not have been able to communicate that sense of the place in the same way as the narrator of “Water Dog God,” who’s lived there most of his life.

It’s a real place. The home of a long-time friend who has lived there a long time, himself, but who is in no way like the narrator of “Water Dog God” (nor his counterpart in “A Blessing”).

It’s a real place. The home of a long-time friend who has lived there a long time, himself, but who is in no way like the narrator of “Water Dog God” (nor his counterpart in “A Blessing”).

Chapter 16: I also particularly enjoyed “Fallen Nellie,” which poignantly channels a particular place and milieu—the lower socio-economic rungs of the Alabama Gulf Coast—as much as it does the broad strokes of a woman’s life. What is it, for you, about that region that inspires and intrigues?

Watson: First, I visited there on vacation as a boy, when it was just beach shanties and a couple of old motels and fish houses and undeveloped, lush dunes and vast clean white beaches where you could spend the day seeing hardly anyone else within half a mile or more. When the locals still called it a paradise. Then I was a reporter there in the mid 1980s and wrote a lot of historical features in addition to many stories about environmental issues resulting from rapid development in a fragile ecosystem. I was dismayed at how much the place had changed in so little time. After Hurricane Frederic wiped it out, destroyed all the frail old structures, that was it for that phase of its history.

I once wrote a feature about (or included in a feature) an older woman who’d lived in the pine woods on the Fort Morgan Peninsula all her life, and as I wrote “Fallen Nellie” I imagined this woman as Nellie’s grandmother, though the actual woman I interviewed told me very little if anything about her family. We talked about the place, the changes it had been through from the early twentieth century up to the present time of our interview. As someone who was making no money off the development, of course, someone who loved it when it was simpler and more sparsely populated and more rarely visited by tourism, I felt a lot of empathy for the locals who were trying to get the developers/municipalities/counties to slow down, slow down. But, aside from when the economy forced them to, no one slowed down. Also, it’s still a very beautiful place in the few areas left (relatively) undisturbed, such as the Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge, where the story is set. I lived there again, briefly, in the late ‘90s and again in 2004-05.

Chapter 16: “Alamo Plaza,” in which a family vacations on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, stands apart from the other stories in Aliens; it has a more intimate, reflective tone, more like a personal essay than a short story. Do you feel you’re doing something different there than in the other stories in the collection?

Watson: It’s very home-grown from childhood memories of visiting the Mississippi Gulf Coast and of the way I felt in general as a child, so that’s probably why it feels that way. It’s also why I had such a hard time making a story from it. I don’t think of it as being like a personal essay, though. I think of it as an attempt to write something akin to Eudora Welty’s beautiful but lesser-known story, “A Memory,” which reads as if the narrator is trying to reconstruct a memory containing some kind of very powerful but elusive emotional experience.

Chapter 16: You’ve said that you didn’t come from a literary family, and that literature was not especially important to you when you were in high school. Was there any one event or teacher that got you from “there” to here—to earning an M.F.A., to making a living as a writer and a teacher? Are you surprised by the way things have turned out?

Watson: I had a junior-high-school chorus teacher (I wound up there after being kicked out of Latin for misbehaving) who decided to put on a play, and cast me in a major role. This woman, Anne Wright, was a force, and she all but single-handedly turned us all, for a little while, into pretty damn good teenage amateur actors. Until then I’d been an undersized jock, vandal, at best a scamp. The interest in theater I took from that changed me. In high school, my eleventh-grade English teacher, the late Roosevelt D. Harris, a great educator, also paid attention to me, though I had backslid and didn’t deserve it.

I skipped first year college to try Hollywood, didn’t make it, went back home (married with a child by then), worked in a bar, started junior college part-time while working in a lumber-company wood shop. I was placed (to my true, and I mean it, astonishment) in an honors English class with Mr. Niles Thomas, a Southern literature scholar from Auburn University. His freshman honors class was a class in Southern literature. It was in there, and with his encouragement, that I decided I would try to write and become a college teacher. There were several other great people at that college who helped me, too, including Ronnie Miller, the theater professor, who allowed me to continue doing a few plays until I became incompetent and got it out of my system. Price Caldwell at Mississippi State believed in me and put up with my blossoming ego. Others including Patrick Creevy, Richard Patteson, Joe Stockwell, Nan Michael, and Robert Phillips, to name a few, were such excellent literature teachers. Barry Hannah encouraged me with words and by example at Alabama, as did Allen Wier after him.

Chapter 16: Do you feel any kinship with the many Mississippian literary greats who have come before you: not just Faulkner and Welty but also Barry Hannah, Larry Brown? Is there any Mississippi writing that has played an especially significant role in shaping you as a fiction writer?

Watson: Well, Barry was a huge influence, and then later on a close friend. Larry was also a generous and close friend. We were getting to know each other a lot better just before he died, while I was visiting writer at Ole Miss. Larry was, like Barry, not only brilliant but also a very hard worker who gave me a lot of practical advice against my stubborn and often lazy and reticent ways. I think Welty’s early stories had a significant and early effect on my sense of what a story could be, too.

Watson will be the visiting writer at Nashville’s Montgomery Bell Academy April 25-26. On April 25, he will give a public reading in the Pfeffer Lecture Hall at 5:30 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.

To read Chapter 16‘s review of Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives, click here.