Being Neighborly the Maggie Valley Way

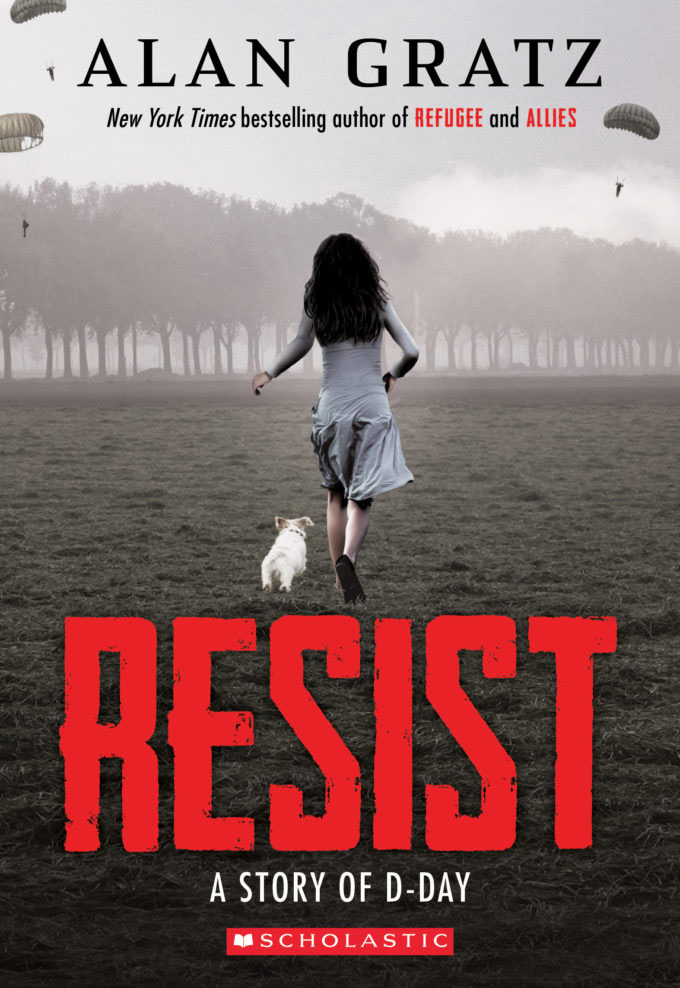

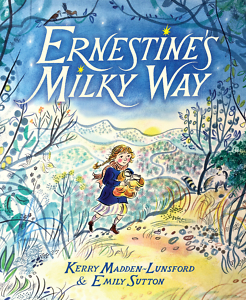

Kerry Madden-Lunsford returns to the Smoky Mountains in her new picture book

Kerry Madden-Lunsford returns to the hollers of Maggie Valley, North Carolina, in her newest picture book, Ernestine’s Milky Way. The Great Smoky Mountains are a setting the author knows well: it’s the home of the Weems family in the Maggie Valley Novels, Madden-Lunsford’s middle-grade series.

In this spirited tale—illustrated by Emily Sutton, set during World War II, and based on a late friend of the author—plucky Ernestine sets out at the request of her pregnant mother to carry two mason jars of milk to a family in need, along the way braving barbed-wire fences, prickly thickets, and plants such as doghobble and devil’s walking stick. As she often reminds herself in the form of pep talks, Ernestine is “five years old and a big girl.” She is disappointed when one of the jars slips from her hands and vanishes “down-down-down into the holler,” but she and her grateful neighbors are happily surprised to find that it spun so fast on its way down the mountain that the milk inside turned to butter.

In this spirited tale—illustrated by Emily Sutton, set during World War II, and based on a late friend of the author—plucky Ernestine sets out at the request of her pregnant mother to carry two mason jars of milk to a family in need, along the way braving barbed-wire fences, prickly thickets, and plants such as doghobble and devil’s walking stick. As she often reminds herself in the form of pep talks, Ernestine is “five years old and a big girl.” She is disappointed when one of the jars slips from her hands and vanishes “down-down-down into the holler,” but she and her grateful neighbors are happily surprised to find that it spun so fast on its way down the mountain that the milk inside turned to butter.

Madden-Lunsford recently answered questions via email about Ernestine’s adventure.

Chapter 16: Can you talk about the real Ernestine, who inspired this story?

Kerry Madden-Lunsford: When I first received an email from Ernestine Edwards Upchurch back in 2005, I fell in love with her name. She described herself as a kind of literary matron, and she’d been on literacy councils and library advisories, in addition to being a social worker in the mountains. She introduced the author John Ehle at the Haywood County Public Library when he came to talk about his body of work around 1981. And she told me early on that I needed to read his work and that my “California family was going to have to learn to spare me” if I was going to write about the mountains. She was so funny and did not suffer fools. She also wondered if I’d based my novel Gentle’s Holler on a family who lived over on “Fie Top Road” in Maggie Valley. I said that I didn’t know anyone in Maggie Valley. I asked what the father did, and she said, “Absolutely nothing. He begat children.”

But when I first came to Maggie Valley to do a week of school visits, Ernestine was out of town helping her daughter, Libby, so I didn’t actually meet her until later in the summer when I went back for a book festival. We made a date to meet at Joey’s Pancake House, a gathering place in town, and I was worried about meeting her, because Ernestine was the real deal. She was born and raised in the mountains of Western North Carolina and, after graduating from college in Berea and receiving a Masters in Social Work from the University of Tennessee, she returned to the mountains to work and raise a family.

But when I first came to Maggie Valley to do a week of school visits, Ernestine was out of town helping her daughter, Libby, so I didn’t actually meet her until later in the summer when I went back for a book festival. We made a date to meet at Joey’s Pancake House, a gathering place in town, and I was worried about meeting her, because Ernestine was the real deal. She was born and raised in the mountains of Western North Carolina and, after graduating from college in Berea and receiving a Masters in Social Work from the University of Tennessee, she returned to the mountains to work and raise a family.

I knew Ernestine liked Gentle’s Holler, but I still felt like this interloper writer from California. But the minute we sat down together, we talked like we had known each other forever. At the end of breakfast, our friendship was sealed, and she me told the people I needed to meet and talk to in order to write my other two Maggie Valley novels to complete the trilogy. My husband met us after breakfast, we drove up to “Ghost Town in the Sky,” and I remember Ernestine said, “You meet yourself coming on these roads” and “A goat wouldn’t go up that road!” She even let me use her cabin the following summer to work on Louisiana’s Song and Jessie’s Mountain. Her own home was filled with books, and nothing made her happier than supporting other North Carolina writers and storytellers.

She was also a wonderful listener, and she insisted that we go together to the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, where she introduced me to the work of Kathryn Tucker Windham, Sheila Kay Adams, and Donald Davis. She adored the playwright Gary Carden, too. She loved books and stories, and when we were together we couldn’t stop telling each other stories.

Chapter 16: What was it like for you to see the ways in which illustrator Emily Sutton visually rendered your story?

Madden-Lunsford: It’s a dream come true. Sometimes when I am reading the book to kids, I stop in the middle of a page and say, “Don’t you just love this picture?” Emily completely captured the world of the Smoky Mountains for me with such tender care, detail, and humor. I love the colors and the way Ernestine’s whole world comes alive on her journey. When Ernestine was in hospice in 2017, I wrote to Emily to ask her if she had any art yet, which is something you are not supposed to do—never bother the illustrator. But I knew Ernestine would not live to see the book come out, and even though she’d read it, I wanted her to see some of the art. And the very next day, Emily sent me four illustrations that Ernestine’s daughter, Libby, shared with her. And Libby said, “Mama got the biggest smile on her face.” I was so grateful that Ernestine got to see a little of Emily’s magic.

Chapter 16: I love the repetition of Ernestine saying, “I’m five years old and a big girl,” and I love how at the end, when she’s most scared, she doesn’t just say this. She yells it. When writing this text, at what moment did it occur to you that you would structure the story with this refrain — and with the rhythmic series of challenges her Mama tells her she will face (thickets of crabapple, prickly gooseberries, etc.)?

Madden-Lunsford: I didn’t know I would structure the story this way. When Ernestine first told me about her job carrying milk through the mountains for her mama, the title popped into my head and stuck there. I was at her home in Maggie Valley, and I took a walk in the early morning—buzzing with stories, the way I always was after listening to Ernestine. Under the gray morning sky, I imagined this little five-year-old girl setting off in the dawn with milk, and I realized it was her “milky way,” guided by the Milky Way.

I loved the story Swamp Angel by Anne Isaacs and illustrated by Paul O. Zelinsky, and I also adored Brave Irene by William Steig. I think countless readings of those stories to my own children got into my heart and head, so I feel like they were lights along the way too. Then I looked up plants of the Smoky Mountains. I had done this with Gentle’s Holler too, but I had forgotten “dog hobble” and “devil’s walking stick.” The names are so beautiful and lyrical that I could feel the music in her journey when I put in the plants. It was later in the revisions with my editor Stephanie Pitts that I began to hear the animals in the bushes making scratching sounds, and so I played with that rhythm.

When my daughter Lucy was little, I told her to be careful as she was tightrope-walking on a tall curb, and she turned and said, “Hey, am I two or am I four? I’m a big girl!” I know that memory of Lucy weaved its way into the story. And the line “I’m five years old and a big girl!” made me laugh as I wrote it. Don’t we all have to all talk ourselves into being brave, no matter what age we are? That’s how it became the refrain. I also think I needed to be brave writing this story. I’d racked up a lot of rejection. I was so busy teaching, but the image of little Ernestine wouldn’t leave me alone.

Chapter 16: In what ways do you think your teaching and/or your students inform your own writing?

Madden-Lunsford: I was having my students write picture books, and I had never really tried to write one. I wrote literary fiction and essays and plays. I mostly considered myself a middle-grade novelist and YA biographer, but picture books were for those people who could write “short” and be so good at it! I wasn’t good at writing short, but I realized I was making my students write picture books, so I thought I could show them how—or at least show them I, too, was willing to try. In my workshops, I try to make sure the students know we are all in it together, working on our stories. I’m not some scribe dictating from on high.

With my first picture book, I began with the friendship of Kathryn Tucker Windham, a white storyteller, and Charlie Lucas, a black folk artist, and how they became best friends in Selma, Alabama. (Remember: I first learned about Kathryn through Ernestine at the National Storytelling Festival.) And when I was writing the biography of Harper Lee, I was lucky enough to get to interview Kathryn. We wound up becoming friends, and she came to see me at the Selma Dallas County Public Library when I gave a talk, and I would drop by to visit her once in a while when Norah and I first moved to Alabama.

I loved the story of Kathryn and Charlie’s friendship and how they met over a tomato sandwich in France. So I wrote it, and my agent liked it, and sent it around. An editor liked it enough to ask me to revise the story but, instead of revising shorter, I revised longer, ridiculously longer. It was so silly, and of course she had to decline the hefty new revision.

Anyway, I took Ann Whitford Paul’s “Writing Picture Books” workshop, and she taught me about page turns. I eventually found Mockingbird Publishers in Alabama, and Ashley Gordon published Nothing Fancy About Kathryn & Charlie.

My royalties for that book went to the Selma Dallas County Public Library in Kathryn’s name. Kathryn was such a beautiful storyteller, Ernestine adored her, and Charlie’s art was whimsical and radiant. Charlie and Kathryn would go looking for junk—tractor seats, shovels, old bicycle wheels, ironing boards—and he would sculpt it into art. And although Harper Lee wouldn’t talk to me, Kathryn did, and when I met her, it was a magical afternoon of cornbread and sweet tea in Selma, and I realized I wanted to tell her story, too.

Writing about Harper Lee led me to so many wonderful Alabama writers and stories, including Helen Norris Bell and Mary Ward Brown. I wrote an essay, called “Words on Fire” about three Alabama women writers of Harper Lee’s generation, which was published in Five Points. I couldn’t get their stories out of my head.

My daughter Lucy illustrated Nothing Fancy About Kathryn & Charlie, and she and I made up our own book tour to rural Alabama libraries to get kids to make art out of found objects. The children made trees out of yarn, string, and buttons, because Kathryn loved trees. We wanted the kids to see how Charlie made art out of anything, and we encouraged them to do it, too—although I do remember a sweet older lady in Scottsboro remarking, “Art of anything? Maybe they should ask permission first before they go cutting up their mama’s curtains?”

A few years later, I also took Jane Yolen’s Picture Book Boot Camp and workshopped Ernestine’s Milky Way and another book, Georgia Ivy and the Old Pump Organ. Georgia Ivy came close with one editor, who really liked the story, but said he needed “oxygen to read it aloud,” as it was so wordy. I constantly need go back to the drawing board over and over with word count. I tell my students that Where the Wild Things Are is just 338 words to give them a sense of what word count means in a picture book.

And Jane Yolen, like Ann Whitford Paul, really encouraged me to look at page turns too. Ann said to our workshop, “You don’t have to write using page turns, but the editor will know you didn’t bother.” And then Jane took both my picture books and offered her suggested page turns from the drafts I’d sent in to participate in the Picture Book Boot Camp in Hatfield, Massachusetts. She also talked about perseverance and sending your work into the world all the time and the notion that stories or poems should be constantly circulating. I learned so much from both those writers; now I never write a picture book without doing page turns, and I make my students do the same. I also use Ann’s textbook Writing Picture Books in my classes.

I think I wanted to challenge myself to write a picture book and show my students they could do it, too. It was the hardest and yet most satisfying writing I’ve ever done. To see the magic of words and images come together was something I had never imagined for myself. As writers, we have to push ourselves out of our comfort zones. And not just writers—aanyone. Because it’s so easy to get stuck or simply too comfortable. I remember I began writing stories as a playwright, and I told myself way back then that I was a playwright, not a novelist. I could barely afford a babysitter while I was rehearsing at the theater. My kids also jumped on the actors and broke the props, so I thought, maybe I’ll write fiction for a while.

Finally, I always share the beautiful late Robin Smith’s essay “How to Read a Picture Book” from the Horn Book because she really insists that the reader slow down and first really see the picture book without reading the words. She even wrote: “LOOK AT THE PICTURES VERY SLOWLY.” And her wise words made me slow down and really study the art on the pages and ask if the pictures tell the story. Besides making book dummies, my students also do storyboards, and they begin to see how form and structure allow for such wonderful possibilities. I really miss Robin, and I was glad to get to know her a little when she came to Birmingham and we all went to the Pancake House. She and her husband, Dean Schneider, are some of the dearest people in this world of children’s literature, and Robin made me see picture books in a whole new light.

Chapter 16: You have been inspired by a lot of novelists in the realm of Southern fiction, and you have made a name for yourself with your own Southern fiction. Are there any contemporary novelists/poets/playwrights writing Southern fiction and nonfiction you would recommend to others who like to read that? Or any great books you’ve read recently that you’d recommend?

Madden-Lunsford: There are so many books I love—from picture books to young-adult books to literary fiction. I love Jacqueline Woodson’s stories, no matter where they are set. I adore the Texas writer Kathi Appelt and her book The Underneath, as well as Angel Thieves, her newest. Margaret Wrinkle’s Wash is terrific, and so is Patti Callahan Henry’s Becoming Mrs. Lewis. I love essays by the young writer Katherine Webb-Hehn.

There are so many beautiful poets in Birmingham. Tina Mozelle Braziel just won the Philip Levine Prize for her new book, Known by Salt. Kwoya Fagin Maples’s new book, Mend, is about how enslaved women were experimented on by the father of modern gynecology. She tells their stories, and it’s so haunting and powerful. Poet Ashley Jones is a visionary who has also started the Magic City Poetry Festival; she is also an incredible teacher. It’s exciting to see the city change through literature from the time I moved in 2009. Desert Island Supply Company is a wonderful haven for writers, and they also work with students in the schools.

I love the work of many of my colleagues, including Daniel Anderson, Lauren Slaughter, Adam Vines, and Jim Braziel. Lee Smith, of course, informed my work as I read her as a young mother living in sunny Los Angeles, raising babies and missing the mountains. I felt like I was home when I read her. I love the whimsy of Lori Nichols, who lives in Birmingham.

I recently read Lisa Patton’s Rush about sororities in Ole Miss, and I found it such a stressful and compelling read. I turn to Irish writers, like Ann Enright’s The Green Road and the playwright Dan O’Brien, who writes nonfiction plays that are luminous.

I can’t wait for Donna Rifkind’s book, The Sun and Her Stars: Salka Viertel and Hitler’s Exiles in the Golden Age of Hollywood. Salka Viertel was Greta Garbo’s screenwriter and beloved friend. And I absolutely adore Carmen Agra Deedy’s work (Martina the Beautiful Cockroach and 14 Cows for America and her storytelling. I got to hear her tell stories at the Athens Storytelling Festival in Athens, Alabama, and I was completely mesmerized and transported with her deep South/Cuban roots and hilarious sense of humor.

I love the work of Linda Sue Park, and she actually did a revision workshop with my students. She talked about writing A Long Walk to Water and so many other stories. I adore Jennifer Richard Jacobson’s The Dollar Kids; Dian Curtis Regan’s Space Boy books; and Laya Steinberg’s Thesaurus Rex</i. I found Jarrett Krosoczka’s Hey, Kiddo heartbreaking and hilarious. I also recently listened to Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins, and I don’t even know how she does what she does.

As for picture books and early readers, my favorite new picture is Little Brown by Marla Frazee. I burst into tears when I finished it because the ending is so beautiful and real. When I am feeling lonesome or sad, I turn to Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad, Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding, or Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory. As for nonfiction, I remember loving Melissa Delbridge’s Family Bible, Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, Mary Karr’s The Liars Club, Rick Bragg’s All Over but the Shoutin’, and the poetry of Jennifer Horne, the poet laureate of Alabama. And I enjoyed Lanier Isom’s Lilly Ledbetter biography, Grace and Grit.

I can’t wait for Casey Cep’s new book about Harper Lee and the book she was going to write, called The Reverend. Cep’s book is called Furious Hours. I’m so happy Cep wrote this one because I really want to see what she discovered about this case. When I was writing the YA biography of Harper Lee, I put my editor, Catherine Frank, through the ringer; I kept finding more material, as Harper Lee was still living, and Catherine finally had to say, “Enough!” But I had secretly hoped that The Reverend was the book they’d find in the vault, instead of Go Set a Watchman—although I wish there had been a few books in the vault.

Chapter 16: Have you ever made your own butter the old-fashioned way—by shaking up a jar of milk until it turns to butter?

Madden-Lunsford: Yes, I have! The first time was when we filmed the book trailer, and I hoped it would work—and it did! Now my husband shakes the mason jar of heavy cream, while I read the story to kids on the book tour. And by the time I’m done reading, it has churned into butter. And then he clogs for kids!

This question also reminds me of the importance of finding writer groups. I took an early draft of Ernestine’s Milky Way to the Hoover Library in Birmingham where the SCBWI local Southern Breeze chapter was meeting on Wednesdays. I didn’t know anyone, but I wanted to read my story aloud to strangers. And in the early version, Ernestine dropped a bottle, but the brother Jimmy (his name used to be Gudger after my husband’s great uncle, but my dear editor, Stephanie Pitts, nixed “Gudger”) found it and brought it home. And so they had more milk for breakfast, and all was fine. And this woman—Kim Maddox, who is a realtor in Birmingham and writing her own stories—turned to me and she said, “I thought when she dropped the bottle and it rolled away, it was to spin into butter. Didn’t you grow up making butter in jars?” I swear I wanted to hug her because I didn’t grow up making butter in jars. I grew up the daughter of a college football coach, and my mother bought sticks of margarine or spray margarine. Yet I knew, as soon as Kim said the words, the milk absolutely needed to spin into butter. And I couldn’t wait to get home and revise it.

That’s the joy of writing groups—people see things you can’t see. As Linda Sue Park says, “We don’t know what we don’t know.” So I try to listen and stay open and write messy stories that take a long way to find their way home.

Julie Danielson, a former school librarian, blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast and writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and the Horn Book. Her first book, Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, was published in 2014.