Bally Girl

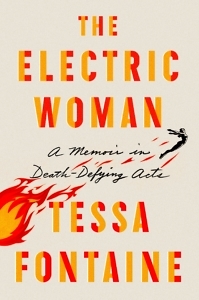

In The Electric Woman, Tessa Fontaine learns about love and fear at the sideshow

In the opening pages of Tessa Fontaine’s memoir, The Electric Woman: A Memoir in Death-Defying Acts, the instructor in a fire-eating class says to her, “You don’t have many instincts for self-preservation.” It’s said with amusement and a touch of admiration, but there’s an unintended irony. Fontaine’s struggle against her powerful impulse to protect herself, physically and emotionally, is at the center of her poignant, ultimately life-affirming story.

Fontaine takes the fire-eating class in preparation for a job in the World of Wonders, “the very last traveling sideshow of its kind.” At least, that’s how it describes itself in 2013, when she signs on with the troupe. Her promised gig involves being a “bally girl” who, dolled up in a corset and fishnet tights, stands in front of the sideshow tent and draws the “marks” with her prowess at handling snakes, swallowing fire, escaping handcuffs, etc. Aside from the brief introduction to fire eating, Fontaine has no performance skills, and she’s deathly afraid of snakes, but she soon learns that her new employers don’t place a high premium on experience. Being game is all that counts.

While Fontaine is testing her nerve with the World of Wonders, her mind is on someone defying death in a much more genuine sense. In 2010, Fontaine’s lively, unconventional mother, Teresa, suffered a hemorrhagic stroke that left her severely disabled—paralyzed on one side, unable to walk or speak or do simple tasks like feeding herself. In spite of serious ongoing complications from the stroke, Teresa’s adoring husband, Davy, decides that the two of them will make a long-dreamed-of trip to Italy in the summer of 2013.

Fontaine doesn’t expect her mother to survive the trip, and she doesn’t expect her stepfather, whom she loves, to survive Teresa’s death. She’s haunted by an image of them being found in their rented apartment in Italy, “an American couple, one handicapped, who have been as quiet as little mice and are now two rotting corpses.” Still, she does nothing to discourage Davy’s plans and goes off herself to join the weird world of the sideshow, where she works eighteen-hour days in the brutal Midwestern heat and sleeps in the back of a truck.

Fontaine doesn’t expect her mother to survive the trip, and she doesn’t expect her stepfather, whom she loves, to survive Teresa’s death. She’s haunted by an image of them being found in their rented apartment in Italy, “an American couple, one handicapped, who have been as quiet as little mice and are now two rotting corpses.” Still, she does nothing to discourage Davy’s plans and goes off herself to join the weird world of the sideshow, where she works eighteen-hour days in the brutal Midwestern heat and sleeps in the back of a truck.

Fontaine weaves the account of her summer with the World of Wonders together with the story of her conflicted relationship with her mother, pre- and post-stroke, and it becomes clear that her time with the sideshow is a kind of penance, or at least compensation, for the ways she feels she failed as a daughter. Not only is she having the kind of adventure her mother once relished and will never have again, but in the harsh society of the sideshow—and it is plenty harsh—she’s also seeking an understanding of the fear and hurt that have made her shy away from her mother’s illness, that have made her refuse to say “I love you,” in spite of the love in her heart. What she ultimately finds is not so much a deeper understanding of herself as a new understanding of her mother:

Story goes: once there was a girl who kept her parents in a fog in her mind. There, it was easier to keep the sick safe and distant. And then one day, the girl saw that actually, while she thought they were napping in the fog, they’d been riding goddamned dragons in there.

The mother/daughter relationship is the emotional core of The Electric Woman, but the wild environment of the sideshow is what propels the narrative. It’s a grueling, sweat-soaked, and often genuinely dangerous way of life that Fontaine enters, and the people within it pride themselves on their toughness and refusal to quit. “Couldn’t hack it” is the standard putdown for anyone who abandons the show. The book makes both the physical misery and the quirky characters so real that there’s an almost uncomfortable intimacy to the storytelling, but Fontaine’s sympathy and admiration for her fellow performers save it from seeming lurid.

In fact, there’s a real tenderness to the way The Electric Woman depicts the sideshow culture, and it mirrors the tenderness of the family drama. In both worlds, Fontaine pushes through her fears to find an unexpected capacity for love.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Literary Hub, and Still. She is the managing editor of Chapter 16.