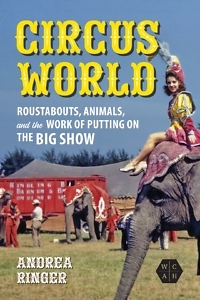

Big Top Labor

Andrea Ringer rewrites the history of the circus from the workers’ perspective

The circus performance began when the train rolled into town. A parade of workers emerged, from clowns to sideshow entertainers to roustabouts, with horses pulling wagons stuffed with trapezes and costumes, animal handlers tending to tigers and bears, and elephants powering the erection of the big top tents. In her lively and fascinating history, Circus World, Andrea Ringer examines the golden age of the circus through the perspectives and experiences of the workers themselves — including the animals.

Ringer is an associate professor at Tennessee State University, where she teaches courses in both American and global history. After earning her Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis, she published articles on the labor history of the circus in a variety of academic journals and edited collections. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Ringer is an associate professor at Tennessee State University, where she teaches courses in both American and global history. After earning her Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis, she published articles on the labor history of the circus in a variety of academic journals and edited collections. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: The circus workers called their workplace “circus world.” What was this world, and what makes the circus a unique and interesting place to write labor history?

Andrea Ringer: For workers, the circus world was their workplace and their home. Most of the year was spent on the road, and many workers brought their families. Even in the offseason, they either prepared for the next season at the winter quarters or performed on other stages. Workers claimed that outsiders could never understand the camaraderie of their world. But circus-goers would prove that they wanted to do so. People really did run away and join the shows, and audiences crossed boundaries each day to interact with the workers and try to catch glimpses of their world.

Workers rallied around the idea of an inclusive circus world. It shaped the ways that labor organizing functioned on the lot. The best description might be that the circus world was like the company towns associated with lumber, railroads, and other industrial workplaces. Workers sometimes did not receive paychecks on time or at all, but they knew they would receive meals and lodging.

Chapter 16: How did you research this story? What kinds of sources illuminate the experiences of circus workers?

Ringer: The circus is an interesting place to write a labor history because it’s unexpected. It also defies what we imagine as an early 20th-century workplace and who we imagine as a worker. This is a labor history of people who did not always fit neatly within that labor category. Children, people with disabilities, high-paid stars, and animals all navigated the circus world as workers who usually had contracts negotiated on their behalf. But in the eyes of management and audiences, their status as workers was also contentious at times.

One of the first sources that inspired this book was one of those famous Ringling Brothers posters that featured a ferocious tiger’s face. I started thinking about every person and animal that worked to create that image. Trainers, multiple tigers, caretakers, audience members — they all were part of this world that created an iconic image. But I quickly turned my attention toward images of the circus that did not depict the big top. Those are the images I chose to feature in the book. The unscripted moments of circus workers taking care of their families, elephants bathing, and circus-goers trying to catch a peek under covered wagons illuminate the experiences of workers and their world. The best find was a letter from a circus worker responding to circus model builders who asked about cage measurements and wagon specifics for this hobby. The former worker answered the questions, but also took the opportunity to discuss his memories of missed paychecks and workplace accidents on that same wagon.

Chapter 16: We tend to think of the circus as rolling into small towns across the United States. But the circus was truly a global enterprise, wasn’t it?

Ringer: Yes, and it was a mobile town itself. It was perhaps more global than any other workplace in the early 20th century. Circus management took advantage of lax labor and immigration laws, which made the working class of the circus incredibly diverse. But management also depended on a global workforce under the tents. They advertised circus stars as hailing from all over the world. The shows had agents who worked within colonial networks to secure people and animals. Often, workers from these spaces had no option to sign their own contracts or negotiate terms of employment.

Ringer: Yes, and it was a mobile town itself. It was perhaps more global than any other workplace in the early 20th century. Circus management took advantage of lax labor and immigration laws, which made the working class of the circus incredibly diverse. But management also depended on a global workforce under the tents. They advertised circus stars as hailing from all over the world. The shows had agents who worked within colonial networks to secure people and animals. Often, workers from these spaces had no option to sign their own contracts or negotiate terms of employment.

Chapter 16: In one memorable phrase, you label circus labor as an “interspecies workforce.” Why view the animals as laborers? What light does it shed?

Ringer: The animal segment of the circus workforce was substantial. In the most impressive shows, nearly 50 elephants, dozens of large cats, and hundreds of horses traveled with a single show through an entire season. If equestrian riders were workers under the big top, the horses performing the tricks were workers, too. The book explores how audiences sometimes had trouble seeing the circus as a workplace, so those equestrian riders and the horses they rode were easily overlooked as workers.

People and animals also performed a second shift each day, erecting tents and preparing the circus lot. Circus management was quick to label animals as happy workers when they were pulling equipment around the circus lot. The trainers, tamers, and keepers profiled in the book often had longer working relationships with their animal co-stars than they did with any of their human co-workers. How well they could maintain that relationship often determined the shows they worked for, the kinds of positions they held, and their longevity in the circus industry. Seeing animals as workers in the circus and elsewhere in the historical record offers us a more complete picture of history.

People interact with animals every day, but we sometimes pretend that history contains just people. Interspecies workplaces acknowledge the ways that animals aren’t machines, even when management probably wishes that they were. Instead, they act in unruly and autonomous ways in workplaces.

Chapter 16: The circus grew popular in concert with the first wave of the feminist movement in the late 19th and early 20th century. How did women workers shape the image and success of the circus?

Ringer: Women were very visible workers, which made the New Woman movement and first-wave feminism easy to take hold in the circus world. Circus management embraced associations with center ring acts and feature stories in circus programs that reminded audience members that circus women were upholding a standard for working women. But like other industries, women performed invisible labor to create an efficient workplace. Because there was often a nonexistent line between work and home for circus workers, they were also raising families on the lot and sewing clothes during their downtime.

The circus was filled with babies, so I use motherhood to examine the circus world across species and age. Some women worked as a “circus mother,” collecting a paycheck to care for young circus workers. Other circus workers worked through their pregnancies and mothered their own children in the backyard of the show. They raised a new generation of circus workers who would claim to be part of a family dynasty. Circuses also valued young animals as trainable and financially valued animal mothers for restocking their menagerie.

Chapter 16: What caused the decline of the golden age of the circus? How does Circus World explain the roles of management and labor in this phenomenon?

Ringer: It’s impossible to ignore the rise of other, more compelling forms of entertainment, but a labor perspective shifts the historical narrative. The circus was a massive undertaking — thousands of people and animals moving across the country on rails each day, some as uncontracted workers. It was also a dangerous workplace with a variety of work hazards. People (including children) and animals died every year in circuses. Child labor laws, the collapse of animal trade networks, and insurance premiums made the circus into an expensive industry.

In many ways, management’s inability to realize how crucial circus workers were to the popularity of the industry undermined the shows. They tried to stay in step with entertainment trends, like color-coordinated acts. But they abandoned workers when labor became too expensive, such as when the Ringling show replaced live musicians with pre-recorded music to avoid a strike. The book shows that even when management miscalculated exactly what made the circus world, workers rarely did.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.