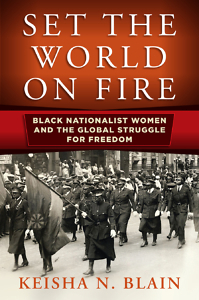

Black Women Who Changed the World

Keisha Blain talks with Chapter 16 about a lost slice of American history

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on October 15, 2018.

***

Even a seasoned historian might not recognize the names of Amy Ashwood, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, Celia Jane Allen, and Amy Jacques Garvey. But as Keisha Blain demonstrates in Set the World on Fire, these women shaped the discourse of black nationalism in the era before Black Power. With creativity and pragmatism, they altered the trajectory of American politics.

Blain is an award-winning historian who writes on race, politics, and gender. She earned a Ph.D. from Princeton University and currently teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh. She also serves as president of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS), as well as senior editor of the organization’s popular blog, Black Perspectives.

Blain is an award-winning historian who writes on race, politics, and gender. She earned a Ph.D. from Princeton University and currently teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh. She also serves as president of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS), as well as senior editor of the organization’s popular blog, Black Perspectives.

Chapter 16: The historical figures at the center of Set the World on Fire are outside the halls of power: they are black, they are women, they are poor or working-class, and they advocate ideas that fall outside the political mainstream. What can their story tell us about the broader contours of American politics?

Keisha Blain: These women’s stories broaden our understanding of American politics by challenging the neat frameworks that so often dominate mainstream historical narratives. They depict the range of protest strategies and tactics individuals have employed to resist domination, degradation, and exploitation; and they capture the depth and complexity of black political thought and praxis.

Ultimately, Set the World on Fire reveals how black women, especially members of the working poor and individuals with limited formal education, have functioned as key leaders, theorists, and strategists at the local, national, and even international levels. Through their writings, speeches, and political activism in the twentieth century, they helped to transform American society and improve conditions for people of color across the globe.

Chapter 16: The premier black nationalist organization of the 1920s, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), revolved around the charismatic leadership of a man, Marcus Garvey, and it promoted a masculinist ideal for black progress. Did any space exist for women to shape the UNIA?

Blain: Certainly—and the UNIA would not exist were it not for women who helped to shape it in the first place. In 1914, when Marcus Garvey launched the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Jamaica, Amy Ashwood—who later became his first wife—was the organization’s first secretary and co-founder. The organization’s earliest meetings were held at the home of Ashwood’s parents. When the organization’s headquarters relocated from Jamaica to Harlem, Ashwood was actively engaged in its affairs. In addition to serving as general secretary in the New York office, she helped to popularize the Negro World, the UNIA’s official newspaper. She also contributed to the financial growth of the organization, relying on her parents’ money to meet some of the growing expenses. From the outset, therefore, women were instrumental to the UNIA’s success and they certainly found a space in the organization to shape the UNIA, despite the patriarchal structure.

Chapter 16: Perhaps the most fascinating character in the book is Mittie Maude Lena Gordon. What does her story reveal about the nature and history of black politics?

Chapter 16: Perhaps the most fascinating character in the book is Mittie Maude Lena Gordon. What does her story reveal about the nature and history of black politics?

Blain: Mittie Maude Lena Gordon’s story challenges mainstream historical narratives on the black-freedom struggle. Too often this history focuses on black men, sidelining black women and diminishing their contributions. And even when we center the ideas and experiences of black women, we are often thinking about middle-class and elite women.

By bringing Gordon’s story to the center of the narrative, then, I show how working-poor activists like Gordon successfully led “from the margins” in the face of government repression and with limited financial resources and support. I also highlight the varied political strategies and tactics these activists employed—even the most unconventional ones. And I highlight the varied unlikely political alliances they formed in their efforts to improve the political and economic standing of black people in the United States and abroad.

Chapter 16: Set the World on Fire traces a strange story: an alliance, of sorts, between a black nationalist political organizer named Celia Jane Allen and Theodore Bilbo, the rabid white supremacist senator from Mississippi. How did this come about? What was the result?

Keisha Blain: The alliance between Celia Jane Allen and Theodore Bilbo is one example of the unlikely—and controversial—alliances that black nationalist women established during the twentieth century. The story is complex, and there are many factors that motivated Allen’s decision to reach out to Bilbo. It is also significant to note that these women were drawing inspiration from earlier black-nationalist efforts. During the late-nineteenth century and early-twentieth century, several black activists and intellectuals relied on the assistance of white supremacists and ardent segregationists to help advance emigrationist movements. White supremacists relished the idea of black people leaving the United States, and they were certainly eager to back these proposals.

Ultimately, I would emphasize here that Allen and other women in the book viewed alliances with white supremacists as strategic. In some ways, they were because they helped these women move closer to accomplishing their political goals. In 1939, for example, Bilbo presented the Greater Liberia Bill before the U.S. Senate, which called for government aid to assist black people willing to leave the United States to relocate to West Africa. The bill represented the culmination of these women’s grassroots efforts and was only possible because of their many years of organizing and lobbying.

Chapter 16: Would you call these women feminists? Why or why not?

Blain: The women I profiled in the book did not call themselves feminists. At the same time, I think it’s important not to lose sight of these women’s feminist views, which is why I describe them in the book as “proto-feminists.” My use of this term was intentional because I wanted to emphasize how many of these women’s strategies and approaches mirrored later feminist movements. I also used the term to signal how these women’s ideas on gender equality were still being developed.

In the end, I would argue that these women were feminists insofar as they often articulated a critique of male supremacy and attempted to change the patriarchal structures of the organizations in which they were active. But this was not always the case. At times, they were complicit and actively involved in upholding masculinist dictates, and sometimes they maintained and supported patriarchy. These realities underscore the complexities and even contradictions of these women’s ideas—themes that run throughout the entire book.

Chapter 16: What legacies did these women leave for the civil rights and Black Power movements of the 1950s and 1960s?

Blain: Through their many writings and speeches, which circulated throughout the United States and other parts of the globe, the black women I discuss in my book played a key role in keeping black-nationalist and internationalist ideas alive in public discourse. These women laid the groundwork for the generation of black activists who came of age during the civil-rights/Black Power era. In the 1960s, many black activists—including Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Robert F. Williams, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael—drew on these women’s ideas and political strategies.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.