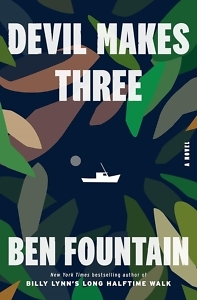

Blood and Gold

Power, desire, and survival collide in Ben Fountain’s Devil Makes Three

Ben Fountain’s new novel, Devil Makes Three, takes us to Haiti, that most fascinating and perplexing of countries— and, of course, the subject of a great deal of brilliant literary writing.

Much of that writing depicts white expatriates who function as avatars for the novels’ Anglo/American audiences, effectively interpreting the country’s mysterious practices (Vodoun — or, more familiarly, Voodoo) and its brutal political upheavals. This kind of writing is risky business these days. In 2023, only a writer with Ben Fountain’s bona fides — and his nerve — can publish a book about Americans behaving badly in an impoverished country overwhelmingly populated by the descendants of enslaved Africans at one of its most violent and politically fraught historical moments.

But Devil Makes Three is not a novel about white Americans using Haiti as an exotic background for their personal transformation. Rather, it is principally about the ways in which the wishes and desires of Americans — both private citizens and agents of the state — end up creating more problems than they solve, disrupting and sometimes ending the lives of innocents. It’s also about the ways in which these genuinely well-meaning people in power can end up choosing “the necessary evil” so often that they lose sight of which evils are necessary, and along the way, become something other than they intended to be.

A sprawling, wildly ambitious book, Devil Makes Three combines elements of suspense/adventure writing, cultural history, socio-political critique, and romance. Just as the book doesn’t fit one genre, it has not one but three protagonists. We are introduced first to Matt Amaker on the day in 1991 when Haiti’s first democratically elected president, Jean Bertrand Aristide, fled to the United States amidst a coup d’état led by high-ranking military officers uninterested in taking orders from a leftist priest. Matt is essentially a tramp and a diving bum lured to Haiti by his friend Alix Variel, a naively ambitious young entrepreneur and the scion of a prominent Haitian family. When the military officers behind the coup “annex” Matt and Alix’s beachfront property and turn it into a clandestine shipping port, Alix proposes that they utilize Matt’s expertise to salvage valuables from the wreck of a Spanish ship, not yet discovered and pilfered by treasure hunters, that lies off the island’s southern coast.

Matt nurses an intense crush on Alix’s sister Misha, a brilliant Ph.D. student in French literature who comes home to visit her family and ends up stranded by the coup. Alix becomes entangled with Audrey O’Donnell, aka Shelley Graver, a young CIA operative posing as an embassy employee, whose idealistic intentions clash sharply with the deceptions and manipulations required to gather intelligence in an environment controlled by sociopaths with personal armies.

The story is conveyed through the disparate perspectives of Matt, Audrey, and Misha. Matt wants to make a living in a place he’s come to think of as home. Audrey wants to advance the interests of the United States, by whatever means are required. Misha wants Haiti to come to its senses and for its story to cease being a tragedy.

Fountain’s genre-straddling ambitions are both spectacular and, at times, overwhelming. Interested in an adventure story with gorgeous descriptive writing about picturesque beaches and kaleidoscopes of color and life beneath the ocean’s surface? “His pulse spiked pleasurably as the reef fell away, dark violet shading to purple below and nothing in front but a void of flawless cobalt blue.”

Fountain’s genre-straddling ambitions are both spectacular and, at times, overwhelming. Interested in an adventure story with gorgeous descriptive writing about picturesque beaches and kaleidoscopes of color and life beneath the ocean’s surface? “His pulse spiked pleasurably as the reef fell away, dark violet shading to purple below and nothing in front but a void of flawless cobalt blue.”

How about lust and love and the kind of graphic sex scenes once de rigueur in the popular adult fiction of the 1970s? “The first time she brought out the riding crop, he thought she was joking, but no, she actually meant them to use it.”

Perhaps a little espionage and hair-raising proximity to danger? “She held her Glock low — no memory of taking it from the glove compartment — and time was doing that weird accordion thing it did in emergencies, expanding, contracting, bunching up, flattening out.”

And last but certainly not least, how about socio-political realism, in which the folly of powerful men amplifies and exacerbates the suffering of an already long-suffering people? “You couldn’t get ahead of it, Misha thought, the noise, the constant screech and caterwaul of suffering children, you were frantic and paralyzed both.”

Only a writer of Fountain’s immense talents can throw all of these ingredients into the same stew without seasoning it too strongly to stomach. And for the most part, he pulls it off. Fountain’s obvious love for Haiti and its people and his moral outrage at their callous treatment both by the U.S. government and their own leaders can boil over a little too hotly and too often, but he’s too good a storyteller for the excesses to sour the soup.

Devil Makes Three strikes me as being both a bit of a throwback and a Hail Mary. Its characters, settings, and plot call to mind the edgy, nihilistic Vietnam War-era literary novels of international intrigue by the likes of Robert Stone, but also the pulpier work of John LeCarré, Frederick Forsyth, and Robert Ludlum.

Its themes and the erudite lyricism of its prose evoke the sensibilities of virtuoso novelists of the post-Vietnam expat experience like Bob Shacochis and Paul Theroux.

But when I asked myself what was the last novel I’d read that struck me as being so wholly distinct in the urgency, ambitiousness, and exuberance of its author’s voice, the answer was Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, by — you guessed it — Ben Fountain. The man writes with a kind of reckless daring and a passion for life and language that seems all too rare these days. Devil Makes Three may be a hard book to classify, but it’s an easy book to love, and nearly impossible to put down.

Ed Tarkington is the author of two novels: The Fortunate Ones (2021) and Only Love Can Break Your Heart (2016). He lives in Nashville.