Books and Rock, Love and Theft

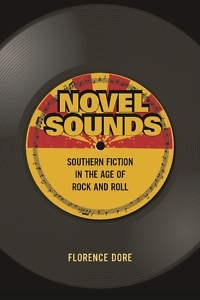

Florence Dore explores early rock’s relationship to Southern fiction in Novel Sounds

In the closing pages of Novel Sounds: The American Novel in the Age of Rock and Roll, Florence Dore invokes the cultural discussion surrounding Bob Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. Whatever you think of the fact that Dylan won, arguments about the prize point to a mistaken cultural belief that literature and rock and roll have “irreconcilable histories,” according to Dore—one refined and the other lowdown.

Throughout Novel Sounds, Dore explores early rock and roll’s influence on postwar Southern novelists, zeroing in on these writers’ use of the ballads of the British Isles and of African American blues traditions. Just as those musical forms rose up, reconstituted as rock and roll during the 1950s, postwar Southern novels remade the same traditions, creating an aesthetic that Dore calls “minstrel realism.” The technology involved in this pivotal moment of musical history also informs these novelists’ work, emerging as new cultural elements begging to be exploited in the construction of fictional characters and their worlds: “The increasing electric buzz of the ballad form was in any case for them a provocation to create their own novel sounds,” she writes.

Throughout Novel Sounds, Dore explores early rock and roll’s influence on postwar Southern novelists, zeroing in on these writers’ use of the ballads of the British Isles and of African American blues traditions. Just as those musical forms rose up, reconstituted as rock and roll during the 1950s, postwar Southern novels remade the same traditions, creating an aesthetic that Dore calls “minstrel realism.” The technology involved in this pivotal moment of musical history also informs these novelists’ work, emerging as new cultural elements begging to be exploited in the construction of fictional characters and their worlds: “The increasing electric buzz of the ballad form was in any case for them a provocation to create their own novel sounds,” she writes.

Dore, a Nashville native who teaches English at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, lays out her argument with four in-depth essays. In “Fugitives and Futility,” she looks at the possibilities that the development of audiotape brings to the “agrarian ballad novels” of Donald Davidson and Robert Penn Warren. The second chapter focuses on the notion of “the book as sound medium” in William Faulkner’s novel The Town. In “The Ballad’s Gender: Femininity and Information in Georgia,” she presents especially intriguing analyses of the way radios figure into the scenes of Carson McCullers’s Ballad of the Sad Café and Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” The book’s final chapter, called “The Lead Belly Thing,” looks at the presence of record albums in William Styron’s novel Set This House on Fire.

The book barrels straight into the thornier points of how these white authors incorporated the vernacular of blues songs. Southern writers like Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, and Flannery O’Connor inevitably fall into the “mix of regard and appropriation of African American forms” that critic Eric Lott has described as “love and theft” (a phrase Dylan then lovingly stole for his own album title).

The book barrels straight into the thornier points of how these white authors incorporated the vernacular of blues songs. Southern writers like Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, and Flannery O’Connor inevitably fall into the “mix of regard and appropriation of African American forms” that critic Eric Lott has described as “love and theft” (a phrase Dylan then lovingly stole for his own album title).

But Dore maintains that such work involves far more complex motives than those that gave rise to malicious appropriation, such as blackface. She contends that “these authors portrayed ballads from both sides of the color line in order to examine the undoing of the ballad form’s racial logic, a cultural phenomenon that was also enabled by radio, as racially ambiguous musical sounds came blasting out of them from across the United States and beyond.”

Novel Sounds is a work of literary criticism written largely in academic language. But threaded throughout the book’s detailed, well-constructed arguments are nuanced imagery and surprising passages, which legendary music journalist Greil Marcus has called the book’s “punk-rock ricochets.” These moments bring the book into the realm of general nonfiction, making Novel Sounds a pleasing option for readers who enjoy celebrated music writers like Marcus or Peter Guralnick.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.