Bright Beads on a Thread

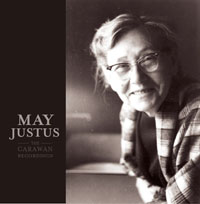

For May Justus, the late children’s author from East Tennessee, folksongs were inextricably linked to storytelling

A Smoky Mountain native, devoted teacher of Appalachian children, and author of more than sixty books for children, May Justus lived just over a hill from the Highlander Folk School, the famous East Tennessee institution that fought trumped-up charges of Communist affiliation by state legislators during the first stirrings of the civil-rights movement. (As a result, state officials ultimately confiscated the school’s library—which Justus helped create—and forced it to relocate from Grundy County to its current location outside Knoxville.) “People would drive by and annoy the folks at Highlander,” says Brent Cantrell, executive director of Jubilee Community Arts, an Appalachian cultural center in Knoxville. “May had a little house with a porch near the entrance of the Center, and she would chase off with a shotgun anyone trying to bother the students.”

Justus was not only the school’s neighbor and watchdog; she was also its secretary-treasurer and a supporter from its inception, having taught at the Summerfield School from which Highlander evolved. She was also a beloved, iconic, community figure, deeply rooted in East Tennessee, where she taught countless children to read.

Justus was not only the school’s neighbor and watchdog; she was also its secretary-treasurer and a supporter from its inception, having taught at the Summerfield School from which Highlander evolved. She was also a beloved, iconic, community figure, deeply rooted in East Tennessee, where she taught countless children to read.

In her ninety-one years, Justus rarely traveled from East Tennessee. But though she stayed close to home, her books, written over half a century, were read widely and reviewed in the national media, awarded prizes, and collected in libraries. In them, young readers were taught “to read beyond the words, to respect and live by the values of their southern Appalachian heritage,” writes George Loveland of Ferrum College, an authority on Justus’s life and work. In books like Peter Pocket, Honey Jane, Dixie Decides, Jerry Jake Carries On, Use Your Head, Hildy, and The Other Side of the Mountain, among many others, Justus celebrated and preserved the flavor of that culture: the young characters speak in Appalachian dialect, enter fiddling contests, harvest potatoes, weave rugs, make regional treats like sorghum molasses candy, and live lives dictated by the fluctuation of the seasons. Songs and music are central to their lives: almost all of Justus’s books feature scores of songs from the mountain folk and ballad tradition that her mother, a singer, and father, a fiddler, shared with her. Many of her storylines included a fiddle player or two.

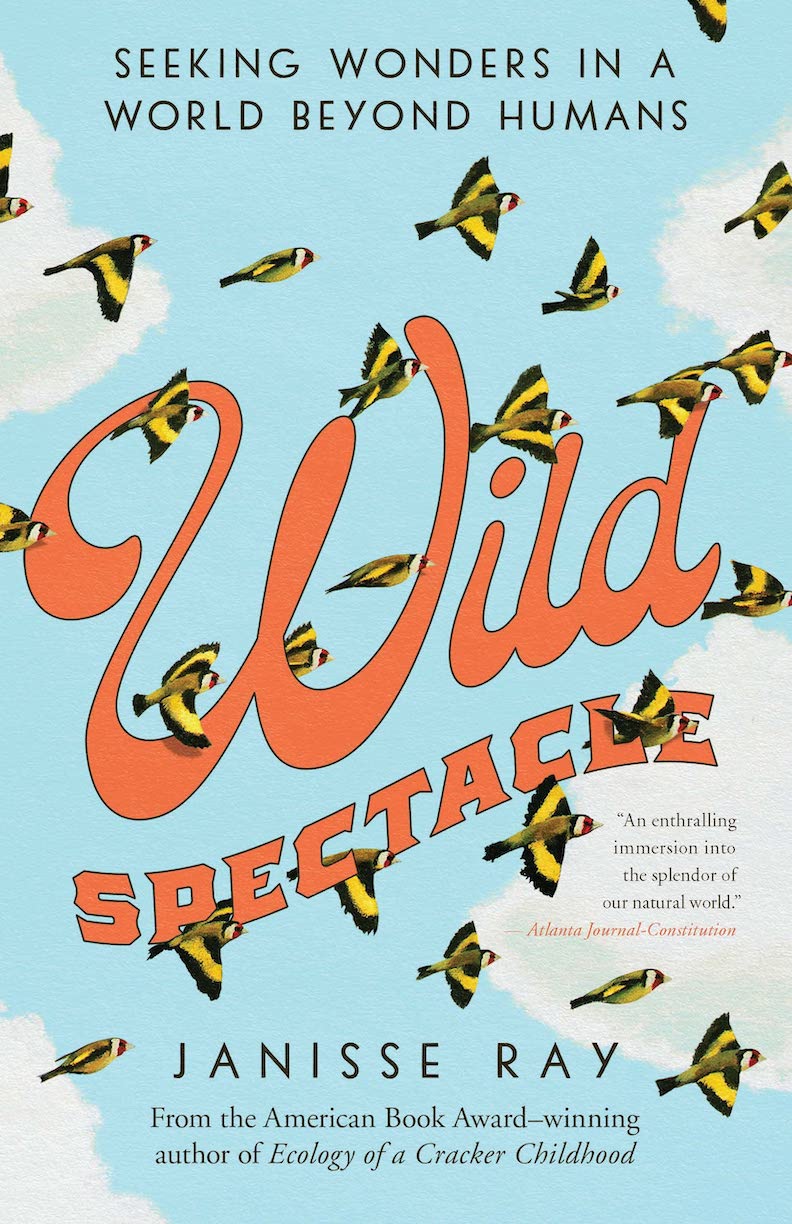

Now the Tennessee Folklore Society and Jubilee Community Arts, an Appalachian cultural center in Knoxville, have released May Justus: The Carawan Recordings, a collection of those traditional mountain folk songs and ballads, sung by Justus and recorded some fifty years ago by Guy Carawan, a folk musician and musicologist best known for introducing the song “We Shall Overcome” to the student protestors of the civil-rights movement. Carawan met Justus through the Highlander Folk School, where he was a volunteer director of the school’s music program in 1959.

Carawan, presumably, saw in Justus a musicologist’s jewel, a rare find: she was a living practitioner of an oral tradition, a repository of songs that had been shared over many generations. The ballads Justus absorbed from her parents were studded with rich cultural detail, but their words were rarely written down, and evidence of the tradition could disappear with the passing of its practitioners. “There’s a lot of good music produced in this part of this world, through the meeting of the British and African traditions,” Cantrell says. “The old style of ballad singing is not particularly commercial. So any opportunity to preserve [the songs] is important, and that’s why we did this.”

Carawan first recorded May Justus in 1959, during his second visit to the Highlander School. He returned and made a second recording in 1961. Both sessions are included on The Carawan Recordings. The recordings sat on Carawan’s shelves for many years until, in 2005, he shared them with Cantrell. Cantrell knew of May Justus, but he’d never heard her sing. “I was aware of her as a children’s author, but I didn’t realize there was that body of recordings of her work.” He in turn passed them on to the late Charles Wolfe, a professor at Middle Tennessee State University and an American roots-music historian, and together they decided to produce the recordings. In 2006, Wolfe and Cantrell were readying them for release when Wolfe died suddenly. With him disappeared the liner notes, and the release was back-burnered until last year.

Guy Carawan’s recordings of May Justus abide as examples of the British-American ballad tradition. Some of the songs can be traced back to England, while others were composed in response to dramatic happenings of their time. “Wrecks, murders, murdered girls—they would sing ballads about the same sort of things you’d see on the evening news today,” Cantrell says. “You know, if it bleeds, it leads? Back then if it bled, it got a ballad.”

But Justus’s songs are also artifacts specific to her birthplace, Tennessee’s Cocke County, adjacent to the North Carolina border. Prior to widespread recording and broadcast technology, musical traditions and their characteristics were unique to limited geographic areas, with little cross-pollination from one community to the next. “One would have its own repertoire of songs, and you’d go fifty miles and those people would have their own set of songs,” Cantrell says. Justus’s Cocke County tradition “has not been as well documented as the Fentress County tradition or [others],” Cantrell says. “So these recordings of May provide us a window into that tradition. There are a few other folks from that tradition who have been recorded, but not a lot.”

But Justus’s songs are also artifacts specific to her birthplace, Tennessee’s Cocke County, adjacent to the North Carolina border. Prior to widespread recording and broadcast technology, musical traditions and their characteristics were unique to limited geographic areas, with little cross-pollination from one community to the next. “One would have its own repertoire of songs, and you’d go fifty miles and those people would have their own set of songs,” Cantrell says. Justus’s Cocke County tradition “has not been as well documented as the Fentress County tradition or [others],” Cantrell says. “So these recordings of May provide us a window into that tradition. There are a few other folks from that tradition who have been recorded, but not a lot.”

In the liner notes for the recordings, Justus offers her own reflection on the ballads: “People who hear them tell me they are ‘real Americana.’ For me they are like bright beads that I strung on a thread long ago and treasure as a sort of keepsake. Each one reminds me of a person or place I used to know.”

In the 1950s and 60s, Justus walked a tightrope, allied during a volatile time to both the culture of the progressive, egalitarian-minded Highlander Folk School and that of the families who had carved lives out of the Appalachian mountains for generations and were sometimes suspicious of the newcomers. Her efforts to bridge those worlds did not always go smoothly: for her support of the school and its anti-segregationist efforts, she was ejected from her Presbyterian church and turned against by some of her own Grundy County neighbors.

But in his essay, “A Greater Fairness: May Justus as Popular Educator,” Loveland argues that Justus “had become what one historian later called an ‘inside agitator,’ one of those Southerners whose roots drew their nourishment from the region’s best values: a strong and broad sense of community, boundless generosity, a willingness to help all who suffer, and a deep faith in a God who would never forsake those who would stand for right.” Cantrell recalls that Carawan, for his part, found Justus “a fierce woman, very friendly but somewhat fierce.”

She was outraged by discrimination and by the violence that erupted in the face of integration efforts. Loveland writes that Justus was particularly shaken by the bombing of the Hattie Cotton School and by a trip to Nashville with friend and fellow teacher Septima Clark, who was barred from using a whites-only elevator. (In protest, Justus insisted on accompanying Clark in the elevator for blacks.) She channeled her anti-discrimination sentiment into two of her later books, her only works set outside Appalachia: New Boy in School and A New Home for Billy. “She thought people should know that people were persecuting children,” says Tina Hanlon, a professor at Ferrum College who has compiled a bibliography of Justus’s work. “New Boy in School is probably the first book for young readers on desegregation.”

She was outraged by discrimination and by the violence that erupted in the face of integration efforts. Loveland writes that Justus was particularly shaken by the bombing of the Hattie Cotton School and by a trip to Nashville with friend and fellow teacher Septima Clark, who was barred from using a whites-only elevator. (In protest, Justus insisted on accompanying Clark in the elevator for blacks.) She channeled her anti-discrimination sentiment into two of her later books, her only works set outside Appalachia: New Boy in School and A New Home for Billy. “She thought people should know that people were persecuting children,” says Tina Hanlon, a professor at Ferrum College who has compiled a bibliography of Justus’s work. “New Boy in School is probably the first book for young readers on desegregation.”

Though the public library in Monteagle now bears Justus’s name, and her papers are archived at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, May Justus is little known today. Her books, all out of print, would be considered too quaint for contemporary children, but they can be found fairly easily online from used booksellers, Hanlon says, and they offer rich exploration for anyone interested in traditional Southern Appalachian culture. Hanlon’s bibliography of papers devoted to Justus and her work suggests, too, that she is increasingly recognized and studied by scholars of folklore and Appalachian literature. And perhaps now with Carawan’s recordings, she has earned her place in the halls of ethnomusicology as well.

It would all likely suit Justus just fine. “If my own stories and books have a lasting value it is, I hope, in the field of regional literature,” she was once quoted as saying. “For in this field may [be] preserved the history of a people to whom I belong, with whom I am glad to claim kin as a Tennessee Mountaineer.”

To order a copy of May Justus: The Carawan Recordings and hear a few tracks from the CD, click here.