The Human Whisperer

For kids who struggle to read, therapy dogs can be the best teachers

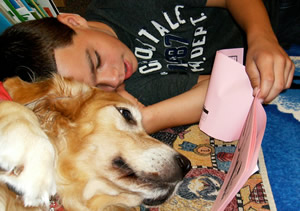

On an early spring day, a visitor comes to Nashville’s Julia Green Elementary School to see a few lucky students. Her name is Emma, and she sits on the floor on a lime green blanket, in front of low shelves packed with books. Before long, a first-grader named Meghan joins Emma and reads her a story, finding her way slowly but confidently through the unfamiliar words. Emma is a pretty good listener: patient, quiet … OK, maybe a bit sleepy. But Meghan doesn’t mind. When she finishes reading, she gives Emma a gentle pat.

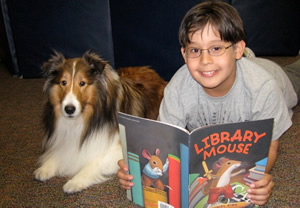

Emma is a twelve-year-old black Lab, and she’s more than just a cute pooch who’s good with kids. She’s a teacher of sorts, employed by a nonprofit called READing Paws that sends specially trained dogs and their handlers into schools and libraries across Tennessee, Georgia, and Central Florida, where they help children learn to read and develop a lifelong love of reading. How does a dog do that? The concept is simple: Children are apt to relax and feel more comfortable, even look forward to, reading if their listener doesn’t intimidate them or tell them to speak up, speed up, or slow down. And it doesn’t hurt if that listener also happens to be skilled in unconditional affection.

“Reading to an adult or their peers, they feel there’s going to be some sort of judgment. But reading to the dogs, they don’t have that anxiety; they don’t feel threatened,” says Rachel McPherson, director of the Brooklyn-based Good Dog Foundation, which, like READing Paws and a number of similar programs around the country, offers literacy mentoring, among other kinds of animal-assisted therapy. McPherson has also written a new book, Every Dog Has a Gift, in which she shares stories of remarkable dog-human relationships culled from her work with therapy dogs over the past twelve years. In it, she includes the story of three dogs who work in New York City schools.

“Reading to an adult or their peers, they feel there’s going to be some sort of judgment. But reading to the dogs, they don’t have that anxiety; they don’t feel threatened,” says Rachel McPherson, director of the Brooklyn-based Good Dog Foundation, which, like READing Paws and a number of similar programs around the country, offers literacy mentoring, among other kinds of animal-assisted therapy. McPherson has also written a new book, Every Dog Has a Gift, in which she shares stories of remarkable dog-human relationships culled from her work with therapy dogs over the past twelve years. In it, she includes the story of three dogs who work in New York City schools.

In McPherson’s book, the children who read to these dogs are all struggling readers, to the detriment of their self-confidence and enthusiasm for learning. But that all starts to change when they begin reading regularly to “Good Dogs” Pepper, Marmaduke, and Abigail. One of the children’s mothers observes her son’s positive transformation: “His teacher says he pays attention more in class. That’s because now he’s getting it; he can read better and he feels better about himself. And his behavior at home has improved as well. He’s getting along with his brother and sister. He has more self-confidence, more of an ‘I can do it’ attitude. He reads aloud at home to me nearly every night, and I can hear the confidence in his voice. And he enjoys reading. I think this program has given him a chance to succeed.'”

Jared’s experience rings true for Merilee Kelley, chairman of Orlando-based READing Paws. “The kids will tell us that it’s the best part of their day, and attendance is usually higher on the days we come,” Kelley says. READing Paws mentoring teams—a dog and handler—currently work in sixteen schools and four libraries across Tennessee.

At the Williamson County Library in Franklin on a recent Saturday, handler Kathy Strunk spreads a blanket in a sunny alcove for Inka, her ten-year-old English Black Lab. Inka is registered with Therapy Dogs International, and also works with special-education students at Kenrose Elementary in Brentwood. She’s been a therapy dog for seven years. “It’s amazing how attached the kids get to the dog,” Strunk says. “If I miss a week, it’s like, ‘Where’ve you been?'”

At the Williamson County Library in Franklin on a recent Saturday, handler Kathy Strunk spreads a blanket in a sunny alcove for Inka, her ten-year-old English Black Lab. Inka is registered with Therapy Dogs International, and also works with special-education students at Kenrose Elementary in Brentwood. She’s been a therapy dog for seven years. “It’s amazing how attached the kids get to the dog,” Strunk says. “If I miss a week, it’s like, ‘Where’ve you been?'”

In the schools, one READing Paws team will typically visit repeatedly with children who are selected for the program, establishing a bond. Young readers in first through third grades are their target, since these are key years for developing literary skills, but the teams occasionally work with older students, often incorporating a journaling or creative writing exercise. In past years, READing Paws teams have even set up camp at Vanderbilt University before spring exams. “The students brought their study materials and explained what they were studying to the dogs. Simply verbalizing it helped them remember it better,” Kelley says.

The notion that dogs can help anxious students (or anyone under pressure) relax isn’t just based on anecdotal evidence. Numerous scientific studies have shown that petting or spending time with man’s best friend can lower blood pressure and increase a sense of wellbeing. And in a recent study, researchers at the University of California at Davis found that third-graders who read to dogs once a week for ten weeks improved their reading skills by twelve percent.

Since reading to a dog naturally reduces stress, it’s not surprising that the benefits of these programs surpass literacy. On a recent Saturday afternoon at the Williamson County Library in Franklin, a five-year-old named Melody reads a book called Little Lamb to a blue Weimaraner named Max. As she reads, her mother looks over her shoulder and helps with any tough words. She brought Melody here not because she has problems with reading, she says, but because the little girl is a bit shy. This is common, explains Max’s handler, Tom Upright: many kids who hesitate to open up with their peers, or who dislike reading aloud, gain courage from reading to the dogs.

Since reading to a dog naturally reduces stress, it’s not surprising that the benefits of these programs surpass literacy. On a recent Saturday afternoon at the Williamson County Library in Franklin, a five-year-old named Melody reads a book called Little Lamb to a blue Weimaraner named Max. As she reads, her mother looks over her shoulder and helps with any tough words. She brought Melody here not because she has problems with reading, she says, but because the little girl is a bit shy. This is common, explains Max’s handler, Tom Upright: many kids who hesitate to open up with their peers, or who dislike reading aloud, gain courage from reading to the dogs.

While Melody reads to Max, three siblings and their parents gather around Inka. The children— five-year-old twins Meghan and Amanda, both wearing pink tops and blue jeans, and their younger brother Gabriel—take turns reading to Inka; while one reads, another will stroke Inka’s back. Mom offers encouragement (“You’re doing really good, sweetie”), and Dad snaps photos. It just so happens that the family has come to the library on a canine reconnaissance mission (they’re researching breeds before adopting a puppy of their own), which has happily coincided with a visit from the READing Paws teams. Here, too, is a side benefit of the program in action: Many kids, some of whom are initially afraid of dogs, get to spend one-on-one time with the animals, as the handlers share tips on how to socialize with them kindly and safely.

The young participants may even spiff up their hygiene, as one pilot study by READing Paws showed: “As handlers, we tell the kids about the things the dog has to do before mentoring: His teeth are brushed, his nails are cleaned, he gets a bath,” says Kelley. “So the kids think about that, and they’ll come in and say, ‘I brushed my teeth this morning!’ The dog did it, so they realize they need to, too. It’s hilarious to watch. Nobody expected that.”

Of course, not just any well-groomed canine can join the READing Paws ranks. The handler-dog team must first be licensed through one of several organizations, such as Therapy Dogs International or the Delta Society. Licensing provides them with liability insurance and qualifies them to work as a therapy team in numerous settings, from schools to hospitals to homeless shelters. Then they complete training through READing Paws, which involves “a lot of consistent exposure to kind and gentle handling by people that they don’t know, in a controlled manner, setting the animal up for success,” Kelley says. But a good temperament and a fondness for children are key—and these are things that can’t really be taught, Kelley notes. “When you find an animal like that, you jump on that. The animals that love to do this are miserable if they don’t have a job. It’s almost like they get depressed if they don’t have one,” she says.

Of course, not just any well-groomed canine can join the READing Paws ranks. The handler-dog team must first be licensed through one of several organizations, such as Therapy Dogs International or the Delta Society. Licensing provides them with liability insurance and qualifies them to work as a therapy team in numerous settings, from schools to hospitals to homeless shelters. Then they complete training through READing Paws, which involves “a lot of consistent exposure to kind and gentle handling by people that they don’t know, in a controlled manner, setting the animal up for success,” Kelley says. But a good temperament and a fondness for children are key—and these are things that can’t really be taught, Kelley notes. “When you find an animal like that, you jump on that. The animals that love to do this are miserable if they don’t have a job. It’s almost like they get depressed if they don’t have one,” she says.

At Julia Green Elementary, children file in one by one to read to Emma, who lays a paw in their laps. Florian, a seven-year-old in glasses, seems a little nervous but reads a story about dinosaurs. When he’s finished, he offers Emma a treat, and Emma’s handler, Brenda Reed, snaps a picture of the two pals. As he’s getting ready to leave, Florian pauses. “I have a question. When will I see you again?”

Next up is a first-grader named Kaylie, who lavishes affection on Emma and reads to her enthusiastically, with Emma’s head resting in her lap. Emma begins to snore a bit, and Kaylie pauses. “You awake? You awake?” Then she answers her own question. “It’s alright. She can hear me,” she says.

For information about volunteering, please visit The READing Paws website.

Rachel McPherson will discuss Every Dog Has a Gift: True Stories of Dogs Who Bring Hope & Healing into Our Lives at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on April 13 at 7 p.m.