Conspiracies of Silence

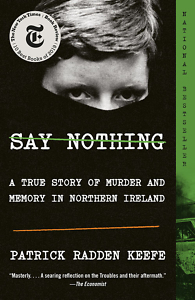

Say Nothing weaves the unsolved case of a disappeared Belfast mother into a history of the Troubles

Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland introduces the mystery at its core in two key scenes: A 38-year-old widowed mother of 10 named Jean McConville is abducted by a masked gang from her Belfast flat in 1972, at the height of the sectarian conflict known as “the Troubles”; and in 2013, 15 years after the Good Friday Agreement largely ended the violence, two detectives from the Police Service of Northern Ireland collect secret recordings from a Boston College archive of oral histories dubbed “The Belfast Project.”

These two threads entwine as Keefe pieces together confessional testimonies of ex-combatants with his own prodigious reporting to put forth a credible theory about who was responsible for McConville’s disappearance and death.

But the larger story of conflict in Northern Ireland is one of collective responsibility. The book’s title comes from a phrase — “Whatever you say, say nothing” — featured in an Irish Republican Army (IRA) propaganda poster warning potential informers and a 1975 poem by the Irish Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney about the “tight gag of place” and the “subtle discrimination by address” that defined the strife.

That tribal culture of silence sometimes abetted atrocities. A telling detail about McConville’s abduction, as recalled by her children, was the housing block’s uncanny emptiness, “almost as if the area had been cleared.” A crueler detail was the neighbors’ seeming indifference, even hostility, to McConville’s orphaned children, left on their own to scrounge for food before being farmed out to dour institutions. Rumor had it that McConville, a born Protestant who married a Catholic, was herself an informer — a stigma that stained even her children.

In Northern Ireland at that time, it seemed there was no greater crime than treachery. “We believed that informers were the lowest form of human life,” a former IRA member named Dolours Price told a journalist. Price and her sister Marian hailed from a family of battle-scarred Irish republicans and achieved a kind of outlaw stardom for taking part in a 1973 London car bombing and staging a prison hunger strike that nearly killed them both. Keefe focuses on the Price sisters in part because their lives would eventually intersect with the woven mysteries of the Boston College secret archive and the McConville kidnapping, but also because their life stories mirror the history of the Troubles — from youthful ideals to violence, self-delusion, and finally disillusionment and regret.

Keefe doesn’t try to pin down the origins of the conflict itself — “It almost didn’t matter where you started the story: it was always there,” he writes. Instead, he zooms in to the combatants’ stories to illustrate how, in a place contorted by generations of discrimination and bloodshed, ordinary people can come to believe that violence is a moral imperative — an idea reinforced by ritual and pageantry. The Price sisters grew up against a backdrop of IRA propaganda murals, tricolor republican flags, and lilies furtively worn to commemorate the failed 1916 Easter Rising. “When Dolours Price was a little girl,” Keefe writes, “her favorite saints were martyrs.”

Of course, few revolutionary ideals survive the realities of revolution. By the time the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, Dolours Price had renounced violence and fallen out with many of her former comrades-in-arms, especially her erstwhile commanding officer Gerry Adams. Adams had miraculously transformed himself from IRA strategist to tweedy Sinn Fein statesman, becoming a key figure in the republican shift from violence to voting as a means to power. Throughout his political rise, he insisted he had never joined the IRA — a claim that few actually believed but that offered the deniability London needed to negotiate a peace deal with him.

Of course, few revolutionary ideals survive the realities of revolution. By the time the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, Dolours Price had renounced violence and fallen out with many of her former comrades-in-arms, especially her erstwhile commanding officer Gerry Adams. Adams had miraculously transformed himself from IRA strategist to tweedy Sinn Fein statesman, becoming a key figure in the republican shift from violence to voting as a means to power. Throughout his political rise, he insisted he had never joined the IRA — a claim that few actually believed but that offered the deniability London needed to negotiate a peace deal with him.

To ex-IRA stalwarts like Price, Adams had betrayed the cause by consenting to anything less than a united Ireland. “Is this what we killed for? she would ask herself,” writes Keefe. “Is this what we died for?” But by masterfully performing the old IRA “say nothing” credo, while repudiating some of the republican movement’s more extreme methods and compromising on its stated goal, the slick shapeshifter Adams helped end the conflict and keep the fragile peace.

“Who should be held accountable for a shared history of violence?” Keefe asks. In the wake of armed struggle, who should answer for the murders of Jean McConville and others who never held a weapon? Such questions have plagued traumatized nations like Cambodia, Rwanda, Spain, and South Africa. Before reconciliation, must there be truth-telling? Or does too much exhumation only reopen wounds best left scabbed over?

As Keefe points out, the Troubles ended in a “queasy sense of irresolution.” Although the paramilitaries had ceased hostilities, even by 2015 tricolor or Union Jack flags still flew in Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods separated by “peace walls,” and most students still attended elementary schools that were segregated by religion. Keefe quotes anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who noted that for most humans throughout history, “the idea that humanity includes every human being on the face of the earth does not exist at all. The designation stops at the border of each tribe…” It’s impossible not to hear a warning in those words about the extremes of tribalism and where they might lead.

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.