Guitar Man

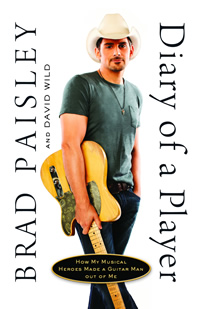

With Diary of a Player, Brad Paisley the brilliant songwriter becomes Brad Paisley the brilliant memoirist

I stop my car at the checkpoint where an aging security guard flips through pages on his clipboard. According to his ID badge, the guard’s name is Hank. Of course it is. He finds my name and asks if I know where to go. I don’t have a clue, and he smiles while directing me to a small parking lot off to the side. I park, gather my notes and digital recorder, and head toward a covered walkway leading to a set of double doors with a small sign that reads “Artists Entrance.” I’m here to interview Brad Paisley about his forthcoming memoir, Diary of a Player: How My Musical Heroes Made a Guitar Man Out of Me, but the sign stops me. For just a moment, I’m no longer a reporter; I’m a half-assed guitar player with an abiding love for the history of country music, and this is my first time backstage at the Grand Ole Opry.

The occasion for this interview—a round-robin affair with journalists from print, radio, and one literary website—is a Number One party celebrating Paisley’s recent chart-topping success with two different songs: “Old Alabama,” a nostalgic sing-along anthem with members of the legendary country band Alabama; and “Remind Me,” a duet with Carrie Underwood, the reigning queen of country radio. Paisley is a busy man. He’s been touring nonstop; he is preparing to co-host the CMA Awards on November 9th; he recently spent a day with the creators of South Park, even lending his voice to a minor character; and Diary of a Player, a memoir he wrote with music journalist David Wild, hits shelves today. The book pays tribute to Paisley’s musical influences, and many of the names will be familiar: Vince Gill, Steve Wariner, Don Rich, and John Jorgenson, to name a few. But the heart of Paisley’s memoir lies with players you’ve never heard of, including his grandfather, Warren Jarvis, and a West Virginia guitar teacher named Clarence “Hank” Goddard, both enormously influential in Paisley’s life.

“Every guitar player is a product of influence, and this book deals with some of the major ones for me,” Paisley tells the assembled group of reporters. “And it’s meant to be inspiring and show that I don’t think I was destined to do this. I don’t think it was a guarantee that I would eventually make my way to the Opry or country music at all, if it weren’t for a grandfather that said, ‘Don’t let [the guitar] get away from you. This could be the greatest thing that’s ever happened to you in your life.’ So I’ve tried to pay tribute to those people like Vince Gill, Steve Wariner, James Burton, and Don Rich. They’re all in the book. I love saying that: it’s in the book. Someone asked me the other day, ‘When did you start playing?’ It’s in the book. This could be a short interview if you ask the right questions.”

“Every guitar player is a product of influence, and this book deals with some of the major ones for me,” Paisley tells the assembled group of reporters. “And it’s meant to be inspiring and show that I don’t think I was destined to do this. I don’t think it was a guarantee that I would eventually make my way to the Opry or country music at all, if it weren’t for a grandfather that said, ‘Don’t let [the guitar] get away from you. This could be the greatest thing that’s ever happened to you in your life.’ So I’ve tried to pay tribute to those people like Vince Gill, Steve Wariner, James Burton, and Don Rich. They’re all in the book. I love saying that: it’s in the book. Someone asked me the other day, ‘When did you start playing?’ It’s in the book. This could be a short interview if you ask the right questions.”

Paisley is a funny guy, as warm and charming as they come, but he doesn’t live a charmed life. “I cringe every time I read ‘the charmed life of Brad Paisley’ in Country Weekly or People or something,” he says. “I do have it made, but the ‘charmed life’ leaves out sleepless nights in a studio and years and years of work. There are people who were born to do this. I don’t think I was one of those. I feel more like Batman than Superman. Superman was always going to save this world. When you can fly and look that good in blue tights, you’re going to be a superhero. But Batman had to figure out how to do it without superpowers. I feel more like that.”

Diary of a Player provides a fair share of wit, insight into the music industry, and fodder for gear-head guitar players, but it’s a far cry from a typical celebrity memoir: “I threw out some stuff from the first draft,” Paisley admits. “I’m not one of these people that’s willing to write a book that makes anybody look bad. I’m not that kind of writer. I’d rather the book be inspiring. I’m probably not one of these people who would ever write a tell-all book.”

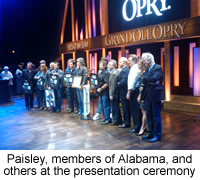

For a guy like Brad Paisley, that’s probably a good plan—at the moment, for instance, Paisley is surrounded by friends, family, press, and seemingly half of the people who work on Music Row. Everyone gathers around the edges of the Opry stage for the informal ceremony and a presentation of Number One plaques, those wall-hanging trophies that signify a hit song and, depending upon how many of them you have, your level of success on Music Row. There are dozens of plaques to present, so many it’s damned near comical. And after a dozen years in the business and almost as many albums, Paisley has already earned a barn full of plaques.

For a guy like Brad Paisley, that’s probably a good plan—at the moment, for instance, Paisley is surrounded by friends, family, press, and seemingly half of the people who work on Music Row. Everyone gathers around the edges of the Opry stage for the informal ceremony and a presentation of Number One plaques, those wall-hanging trophies that signify a hit song and, depending upon how many of them you have, your level of success on Music Row. There are dozens of plaques to present, so many it’s damned near comical. And after a dozen years in the business and almost as many albums, Paisley has already earned a barn full of plaques.

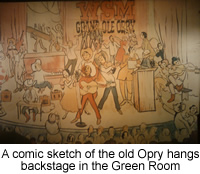

When the ceremony comes to a close, the artists and songwriters spend some time mugging for the cameras and television crews. The radio and print interviews aren’t for another half hour, so I wander around the Opry for a few minutes and take in the atmosphere. Die-hard traditionalists still call it “the New Opry House,” even though the Opry left its old home at the Ryman Auditorium almost forty years ago.

My tastes in country music tend to break down along the lines of Old Opry versus New Opry, fiddle and steel versus Auto-Tune and drum machines. I belong to the camp of believers who contend that country music was born with Jimmie Rodgers and died with Keith Whitley. Some people call us traditionalists, but we’re mostly a bunch of curmudgeons making distinctions where they don’t really exist. In truth, the historical significance of the Opry cannot be overstated. Every wall in the place is festooned with photographs of legendary performers spanning generations, styles, and schools of artistry—from Roy Acuff and Loretta Lynn, to Garth Brooks and Wynonna Judd, to Sugarland and Brad Paisley. It hits me then that if the Opry itself isn’t burdened by tired distinctions of old and new, traditional and modern, perhaps I shouldn’t carry them around either.

My tastes in country music tend to break down along the lines of Old Opry versus New Opry, fiddle and steel versus Auto-Tune and drum machines. I belong to the camp of believers who contend that country music was born with Jimmie Rodgers and died with Keith Whitley. Some people call us traditionalists, but we’re mostly a bunch of curmudgeons making distinctions where they don’t really exist. In truth, the historical significance of the Opry cannot be overstated. Every wall in the place is festooned with photographs of legendary performers spanning generations, styles, and schools of artistry—from Roy Acuff and Loretta Lynn, to Garth Brooks and Wynonna Judd, to Sugarland and Brad Paisley. It hits me then that if the Opry itself isn’t burdened by tired distinctions of old and new, traditional and modern, perhaps I shouldn’t carry them around either.

In fact, Brad Paisley is often regarded by critics and tastemakers as a bridge between old-style country and new. His songs—and he writes or co-writes many of them himself—offer sharp, catchy melodies that are also well-crafted, accessible lyrics that are also artful. And when you listen to any of his cuts, the guitar parts always stand out. They might even bowl you over. His playing is nothing short of astonishing, as acrobatic as Eddie Van Halen, as twangy as Don Rich, and as tone-rich as Albert Lee. But he doesn’t overplay. His guitar work fits the song and elevates it, making it better. If anything, Paisley has built a career out of raising the bar: whether it is a song, a video, a concert tour, or an awards show, he’s always looking for a new angle. “When I was interning at ASCAP years ago,” Paisley tells us, “they said to pretend everyone in town was writing a song with the same title as yours. How do you make your song stand out?”

It’s not surprising, then, that Diary of a Player stands out from most memoirs by contemporary musicians. As he has proven time and again with his songs, Paisley knows how to tell a story, though he did have a great deal of help this time from music-journalist extraordinaire David Wild. (“Extraordinaire is a little generous,” Paisley deadpans. “Normal. Music journalist normal.”) Diary of a Player was actually Wild’s idea: “I had no interest in writing a book,” Paisley says. “But when we worked [together], writing the CMAs last year, he said I should do a book about some of these things. And I realized I needed to be able to read something like this when I was ten. There wasn’t anything that said basically, ‘Here’s what you can do if you practice.’ That’s what this book ought to really be called: Brad Paisley: Here’s What You Can Do if You Practice.”

It’s not surprising, then, that Diary of a Player stands out from most memoirs by contemporary musicians. As he has proven time and again with his songs, Paisley knows how to tell a story, though he did have a great deal of help this time from music-journalist extraordinaire David Wild. (“Extraordinaire is a little generous,” Paisley deadpans. “Normal. Music journalist normal.”) Diary of a Player was actually Wild’s idea: “I had no interest in writing a book,” Paisley says. “But when we worked [together], writing the CMAs last year, he said I should do a book about some of these things. And I realized I needed to be able to read something like this when I was ten. There wasn’t anything that said basically, ‘Here’s what you can do if you practice.’ That’s what this book ought to really be called: Brad Paisley: Here’s What You Can Do if You Practice.”

It was Paisley’s grandfather, the late Warren Jarvis, who gave him his first guitar when he was eight and encouraged him to practice. Jarvis also saw to it that his grandson had the best teacher available by convincing a West Virginia guitar hero, the late Clarence “Hank” Goddard, to take the young Paisley under his wing. Diary of a Player is most revealing when Paisley writes about these men, and most heartbreaking when he writes about the pain of losing them. “Writing it brought it all back,” he tells us. “It made me appreciate Hank, my guitar teacher. It made me appreciate my grandfather. One thing I learned [while writing] this book was how many people collaborated to help me get where I am. I’m sitting here today because of them.”

Right now, Paisley’s sitting in front of a bank of microphones backstage at the Grand Ole Opry. He has just accepted a slew of honors for two different Number One songs. He is loved by millions of fans—and even a few curmudgeonly traditionalists. As the interview comes to a close, Paisley cuts up with a few journalists and leaves to work on his sketches for the upcoming CMA Awards. He’s playing the Opry tonight with Alabama and Carrie Underwood. I pack up my digital recorder, find my way back to the parking lot, and look up to see Paisley’s name digitized on the marquee facing Briley Parkway. He’s arrived without forgetting where he came from. I’m pretty sure his heroes would be proud. They made a guitar man out of him.

To read an excerpt in Chapter 16 of Brad Paisley’s memoir, Diary of a Player, please click here.