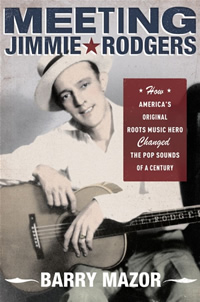

Country’s First Elvis

Barry Mazor discusses the musical reach and influence of American icon Jimmie Rodgers

Jimmie Rodgers became known as “The Father of Country Music,” but as Barry Mazor illustrates in his new book, Meeting Jimmie Rodgers, Rodgers was much more than a musical ancestor of The Outlaws. Though his last recording took place over 80 years ago, his influence remains pervasive in popular music and culture. Mazor goes beyond Rodgers’s biography to explain how he changed not just country music but the landscape of popular music as a whole. For Mazor, Jimmie Rodgers isn’t a relic of music history; he’s a modern icon.

Barry Mazor lives in Nashville and has been writing about American music since the 1970s. He was a long-time senior editor for the roots and pop-music magazine No Depression and is a frequent contributor to the Wall Street Journal. He will discuss and sign Meeting Jimmie Rodgers at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on November 14 at 2 p.m.

Chapter 16: Before we get to the heart of your book, can you provide a bit of context? Who was Jimmie Rodgers, and why is he known as the “father of country music?”

Chapter 16: Before we get to the heart of your book, can you provide a bit of context? Who was Jimmie Rodgers, and why is he known as the “father of country music?”

Mazor: Jimmie was a guitar-playing, singing vaudevillian who cut over a hundred sides for Victor records from 1927 to 1933, many of them songs he wrote, co-wrote, or adapted, hits in his day that have been recorded by hundreds of performers, across musical genres and international borders, time and time again, ever since, right into our own [day]—”T for Texas,” “Waiting for a Train,” “Any Old Time,” “In the Jailhouse Now, “Mule Skinner Blues,” and “Miss the Mississippi and You,” among them.

He was a touring and recording star of something like Elvis proportions, for that day, and known by a variety of monickers, like a Greek god, or James Brown—”The Singing Brakeman” (he’d worked on trains), “America’s Blue Yodeler” (he had a deep feeling for the blues, recorded a lot, and incorporated a distinctive yodel that set off a blue-yodel craze), and eventually, some twenty years after his early death from tuberculosis in 1933, “The Father of Country Music.”

Jimmie sang of subjects and themes that helped define what would come to be known as country music (though he never heard the term in his time), of rough-and-rowdy outlawry and drinking, rambling and hoboing, working hard and winning and losing in love, of life down home with the family and also in the saddle—and with musical backing and a modernizing vocal attack that suggested or started music down the road to honky tonk, Western Swing, cowboy songs, confessional singer-songwriter ballads, and elements of folk, bluegrass, and rockabilly.

Chapter 16: You call Jimmie Rodgers “America’s first roots music hero.” What do you mean?

Mazor: Rodgers was not just a star. He was the first performer in the mass-media age who came from a down-home, working-class sort of background (in his case, out of Meridian, Mississippi), performing music that had ties to that place and its past, who, as he became nationally and even globally renowned, never tried to hide where he was from and who he was but reveled in it and made much of it, even as his musical vistas expanded. His accent was heard on the records, not stifled; he sang about lard and working life and love down home—and kept doing it even as he reached stardom and fairly publicized success and wealth. He was “one of us,” writ large and cool to the folks who could so easily identify with him, and he brought their life and style to the wider world even as he brought the wider modern world to them. That’s what I mean by a roots-music hero, and he cleared the way for that sort of career and impact for others who followed—a Gene Autry, a Bob Wills, an Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash or Bob Dylan, and, for that matter, a Dolly Parton or Sam Cooke, unelected representatives and roots-music heroes all.

Chapter 16: As you point out, Meeting Jimmie Rodgers isn’t a biography but rather a close examination of one man’s influence on 80 years of recorded music. What are some examples of the way Rodgers’s influence reaches beyond what is considered country music?

… [Rodgers] never tried to hide where he was from and who he was but reveled in it and made much of it, even as his musical vistas expanded.

Mazor: It begins with that way of being a roots-music hero, really—how he carried himself and brought along an audience to expansive new places. But, more specifically, he was the first to really bring modern, up close, for-the-microphone-style singing to blues and hillbilly and the old parlor ballads, emphasizing the meaning of words and lines as he sang, clarifying the narratives and stamping his own personality onto everything he sang. That personality combined wit, unmitigated physicality, and joy of performing, presented in ways that have been models for a wide variety of performers. And if we simply look at the image and notion of this man, who often sang of his own story, up on a stage alone with his guitar, riveting people—that’s a model that’s still at work, of course, well beyond the boundaries of country music.

Chapter 16: Your approach, a biography of the music rather than the man, complete with exhaustive documentation in the form of playlists and discographies, is novel. What led you to this approach, and can you talk a bit about the process of writing Meeting Jimmie Rodgers?

Mazor: I decided early on that what I really wanted to do was make the power of Jimmie Rodgers and his music accessible and palpable for people out here in the 21st century, and to really nail down how he’s had this lasting and widespread impact. Rodgers’s multiple images, what people have taken him to be, have mattered almost as much, in that regard, as the music itself. I’d seen books that had looked at the changing images of a Shakespeare or Leonado over the centuries and how those changes were put to use, and thought this eighty-year story might now be long and wide enough to try something like that with Jimmie Rodgers.

That had to take us past his lifetime—since so much of his influence came later—and I really wanted to nail down what this often really vague notion of “influence” over time means, how it’s worked. I wound up interviewing some 80 performers of many stripes, many of them as well-known as Merle Haggard, Doc Watson, Jerry Lee Lewis, and B.B. King, and some less known but major contributors in forwarding Rodgers’s music or ideas, to get at the nature of Rodgers’s impact on them and their music, and doing some deep research on artists no longer with us to reveal Rodgers’s specific impact on them—Bill Monroe, Ernest Tubb, or even Robert Johnson. A not-so-secondary idea was that this would all make for an involving story, structured almost like a mystery.

This was, I guess, a fairly risky thing to do, but for the most part, since the book was published in mid-May by Oxford University Press, there’s been a very gratifying response to it—though not moderate. The American Library Association’s Booklist publication, for instance, called the book “one of the most intelligent, fascinating, and cogent pop-music histories ever.” But then, too, a few people have expressed shock that Jimmie Rodgers dies, in this book, in chapter six out of fifteen, despite being warned that it’s not a conventional biography. It really is the life story of the music, not just of the man.

Chapter 16: The story of the music takes quite a few unexpected—one might even say bizarre—twists and turns over the last eighty years. What are some peculiar places you found Jimmie’s music and influence popping up?

Chapter 16: The story of the music takes quite a few unexpected—one might even say bizarre—twists and turns over the last eighty years. What are some peculiar places you found Jimmie’s music and influence popping up?

Mazor: Well, “bizarre” is probably in the ear of the beholder, but those who come to this story with over-defined expectations are surely in for more than a few surprises. Some of the places Jimmie Rodgers’s music and influence go include the yodeling in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the sexually-charged chants and salutes to the recording artist they call “Chemirocha” by the Kipsigi people of Kenya, the London jazz show-band version of “In the Jailhouse Now,” and the rendition of “T for Texas” Pete Seeger had just sung when the anti-leftist Peekskill Riot incident occurred [in Peekskill, New York, in 1949].

I imagine there are also those who will be surprised by the Rodgers image taken to Broadway musicals, or “Blue Yodel No. 8” as rendered by the psychobilly punk band The Cramps. I showed some video clips of very varied artists performing Rodgers’s songs at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum last spring, and they included what I believe was the first performance by The Cramps within the Hall’s rightfully hallowed walls.