Cracking the Code

Gordon A. Martin revisits United States v. Lynd, the civil rights case that forever changed the South

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: In conjunction with Humanities Tennessee’s exhibition tour of Voices and Votes: Democracy in America, Chapter 16 is revisiting coverage of notable books on civil rights and the foundations of a democratic society. This article originally appeared on October 29, 2010.

***

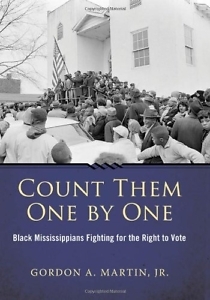

Most Americans are familiar with the landmark civil-rights case Brown v. Board of Education. Less known is United States v. Lynd, the 1962 trial that paved the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which once and for all established voting rights for black citizens. Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote is an account of the groundbreaking trial that put Hattiesburg, Mississippi, at the center of the civil-rights debate. Written by Gordon A. Martin Jr., one of the Justice Department attorneys in the case, the book uses oral history, legal commentary, and first-person reportage to put readers on the front row of a trial that forever changed the nature of race relations in Mississippi and the South.

Though the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed African Americans the right to vote, a black citizen wanting to exercise that right in Hattiesburg during the early 1960s took his life in his hands. No constitutional amendment could change the hearts of men like Theron Lynd, the Forrest County Circuit Clerk who, between 1955 and 1963, routinely thwarted the voting rights of Hattiesburg-area citizens. The Voting Rights Act (which suspended literacy tests and provided for federal examiners and poll-watchers) would change that, but first federal prosecutors had to take down Lynd, whose egregious defense of the status quo was a model for racist politicians throughout the South.

Though the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed African Americans the right to vote, a black citizen wanting to exercise that right in Hattiesburg during the early 1960s took his life in his hands. No constitutional amendment could change the hearts of men like Theron Lynd, the Forrest County Circuit Clerk who, between 1955 and 1963, routinely thwarted the voting rights of Hattiesburg-area citizens. The Voting Rights Act (which suspended literacy tests and provided for federal examiners and poll-watchers) would change that, but first federal prosecutors had to take down Lynd, whose egregious defense of the status quo was a model for racist politicians throughout the South.

Lynd’s methods were simple. When black voter registrants arrived at his office, he would stonewall. White applicants were given a pass but blacks were required to complete literacy tests, their applications rejected for minor inconsistencies. Lynd’s deputies routinely accepted white applications, while blacks were required to file with the clerk himself, who would usually be unavailable. In 1962, only fourteen African Americans were registered to vote in Forrest County.

Martin was part of the Civil Rights Department team charged with proving that Lynd’s activities constituted a pattern of racial discrimination. Martin worked in Washington during the week, analyzing voter registration forms and poll-tax records, but on weekends he and his Justice Department colleagues journeyed to Mississippi, locating blacks who had been denied registration and preparing witnesses for Lynd’s upcoming trial. Those witnesses included obviously qualified teachers, factory workers, and military veterans who attempted to register numerous times only to be told they were unfit.

Decades after Lynd’s eventual conviction, Martin returned to Mississippi to seek out these courageous men and women and their families; the resulting interviews form the backbone of Count Them One by One. In case after case, black citizens like Rev. Wendell Phillips Taylor––who holds two degrees from Columbia University yet was still prevented from voting––express dismay over having been denied their rights and offer their appraisals of the current state of the civil-rights movement.

Other parts of Count Them One by One analyze the intricate ramblings of the 1962-era federal court system. In Lynd’s initial trial, U.S. District Court Judge Harold Cox–– whom Martin paints as an ornery stalwart segregationist––refuses to place the clerk under a temporary injunction. Martin and his colleagues immediately take their case to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which would ultimately rule against Lynd––both in the appeal and his subsequent trial for contempt. “While the legislation of the fifties demonstrated the rise of civil rights on the national agenda,” says Martin, “the empowerment of blacks in the South had to be accomplished in southern federal courts presided over by southern federal judges.”

Occasionally, Martin’s prose gets a little thick for the average reader. Though obviously avoiding legalese, his accounting of post-trial Mississippi Ku Klux Klan activity, for example, is so dense as to be practically incomprehensible. That said, Martin’s recollection of the tangled intricacies surrounding United States v. Lynd is nothing short of phenomenal––that he sometimes struggles to present such detail in readable form isn’t surprising.

Theron Lynd continued to serve as Forrest County Clerk until his death in 1973, but by then the Voting Rights Act had effectively stayed his divisive power. Martin maintains that African Americans in Mississippi currently experience great opportunities––though these do not necessarily include participation in the state’s power structure. “More should come,” he says, “in the state as a whole as they have in Hattiesburg, and, when that happens, we can look back to the early beginnings, to the black witnesses of Forrest County.”