Crime and Punishment (and Race)

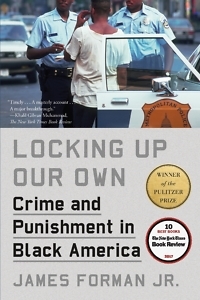

James Forman Jr. discusses his Pulitzer-winning book on mass incarceration, Locking Up Our Own

The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis annually confers its National Book Award on a nonfiction book that furthers understanding of the American civil-rights movement and its legacy. This year’s winner is Locking Up Our Own by James Forman Jr., a book that both illuminates and complicates our understanding of the mass incarceration of African Americans.

James Forman Jr. is a professor of law at Yale Law School. After clerking for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, he spent six years as a public defender in Washington D.C. Locking Up Our Own won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction. It was also longlisted for the National Book Award and named one the ten best books of 2017 by The New York Times.

James Forman Jr. is a professor of law at Yale Law School. After clerking for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, he spent six years as a public defender in Washington D.C. Locking Up Our Own won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction. It was also longlisted for the National Book Award and named one the ten best books of 2017 by The New York Times.

Forman answered questions via email for Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You begin with a story from your time as a public defender in Washington D.C., when Superior Court Judge Curtis Walker gave your young client a familiar lecture about besmirching the legacy of Martin Luther King. What does this story reveal?

Forman Jr.: In the story my client, whom I call Brandon, was facing sentencing for possession of a gun and marijuana. I was asking for probation, and the prosecutor was asking for incarceration at a juvenile facility called Oak Hill. Like too many juvenile prisons around this country, it was a place of violence; Oak Hill was a place of abuse. It was a place where there were no programs—some on paper, but none in reality. It was a place where you left worse off than when you went in.

The judge who had to make the decision in the case was an African American judge. That was not unusual—about forty percent of the judges in D.C. Superior Court were black. Judge Walker looks out on the courtroom and what does he see? A young black man facing sentencing, an African American defense attorney, and a black prosecutor. And he looks at Brandon and he says, “Son, Mr. Forman has been telling me that you’ve had a tough life, that you deserve a second chance. Well, son, let me tell you about tough, let me tell you about Jim Crow segregation.”

The judge had been a child in those years, and he proceeded to lecture Brandon on what that was like. Then he said, “So here’s the thing son, people fought, people marched, people died for your freedom. Dr. King died for you. And he didn’t die for you to be running and gunning and thugging and carrying on, embarrassing your family, embarrassing your community, carrying that gun. So I hope Mr. Forman is right, I hope one day you turn it around. But today, in this courtroom, actions have consequences. Your consequence is Oak Hill.”

I was furious at the judge. The story reveals that not everybody in the African-American community saw mass incarceration as an affront to the legacy of Dr. King. Some, like that judge, saw crime as the affront and saw themselves as defending the legacy of Dr. King by being tough.

Chapter 16: In the 1970s, Washington D.C. implemented tougher penalties for marijuana crimes—an early, local, black-driven element of the war on drugs. Why did black leadership enact these get-tough policies?

Forman Jr.: To understand black support for tough crime laws, we must start with a profound social fact: in the years preceding and during our punishment binge, black communities were decimated by historically unprecedented levels of crime and violence. Spurred by a heroin epidemic, crime rates doubled and tripled in most American cities throughout the 1960s. Two decades later, heroin would be eclipsed by crack, a drug that some contemporaries called “the worst thing to hit us since slavery.”

As they confronted this devastating crime wave, black officials exhibited a complicated and sometimes overlapping mix of impulses. Some displayed tremendous hostility toward perpetrators of crime, describing them as a “cancer” that had to be cut away from the rest of the black community. Others were less severe, pushing for harsher penalties while acknowledging that these measures were insufficient to solve the crisis at hand. Some even expressed sympathy for the plight of criminal defendants, who they knew were disproportionately black. But that sympathy was rarely sufficient to overcome the claims of black crime victims, who often argued that a punitive approach was necessary to protect the African American community—including many of its most impoverished members—from the ravages of crime.

Chapter 16: There was hope that as more African Americans became police officers in the wake of the civil-rights movement, it would better serve the poor blacks who were vulnerable to the criminal-justice system. Was this the case?

Chapter 16: There was hope that as more African Americans became police officers in the wake of the civil-rights movement, it would better serve the poor blacks who were vulnerable to the criminal-justice system. Was this the case?

Forman Jr.: For almost a century, black Americans had been calling on their cities to hire black police officers. This was an important, if forgotten, part of our nation’s civil-rights struggle. But while these demands were consistent, the rationales were not. Some advocates claimed that blacks would make better crime-fighters: they would win black citizens’ trust more easily, could more effectively develop informants in black communities, and, above all, would be more motivated to protect black lives. This final consideration was especially important, given the long history of white indifference to crime, vice, and public disorder in black communities.

Others said that black officers would be less abusive and disrespectful than their white counterparts: unencumbered by racism, they’d be less likely to harass innocent blacks or use excessive force during stops or arrests. Plus, they’d be more discerning—instead of treating all blacks as criminals, they would be able to distinguish decent folks from the criminal element. Still others focused on economics: police jobs were good jobs, with decent pay and even better benefits, and blacks should get their fair share of the pie. Finally, some focused on the symbolic: even if black police acted just like white ones, investing blacks with the power of a badge and a gun sent an important message to Americans on both sides of the color line, particularly given the nation’s historical discomfort with black authority.

The problem is that these rationales often conflicted when put in practice. In addition, few of the people making these claims bothered to ask the new black officers why they were becoming police. Finally, these claims underestimated the extent of the racism that black officers would find when they came onto the job—a racism that limited their ability to be reformers, even if they wanted to be.

Chapter 16: How did the crack cocaine epidemic of the late 1980s and early 1990s shape the policing of black communities such as those in Washington DC?

Forman Jr.: Crack presented a uniquely horrifying threat to black America—exceeding even the heroin crisis of the 1960s. Crack spawned violent drug markets the likes of which American cities had never seen. In their fight for territory, heavily armed gangs turned urban neighborhoods into killing fields. The menace crack presented in turn provoked a set of responses that have helped produce the harsh and bloated criminal-justice system we have today. Most of all, the fight against crack helped to enshrine the notion that police must be warriors, aggressive and armored, working ghetto corners as an army might patrol enemy territory. This hostile, unforgiving mindset wasn’t born in the crack era, but it was then that it became entrenched, influencing even to this day how we think about drugs, violence, and punishment.

Chapter 16: Although you show how African American politicians, judges, and police officials helped shape modern criminal justice policy, you also write that “it is impossible to understand American crime policy without appreciating racism’s enduring role.” Why?

Forman Jr.: Because racism constrained the choices available to black elected officials. A history of Jim Crow, of segregation, of redlining, of wealth discrimination, of the inability to get loans in black neighborhoods, of decisions by the federal government to put highways through black neighborhoods, destroying those communities—all of these things made black elected officials constrained in how to respond to crime and violence.

Racism also explains why black officials didn’t get all they were asking for. Because what you see for the last forty or fifty years is generations of black elected officials saying basically that we have an all-of-the-above strategy to fight crime and violence. “We want more police and more prosecutors, yes, but we also want more money for drug programs, more money for schools, more money for job training, more money for mental health, more money for after school programs. We want national gun control laws to be a companion to the local gun-control laws we’re passing. We want a Marshall plan for urban America, we want the United States to do for black communities what it did for Europe after World War II, to rebuild, to reinvest, to revitalize.”

And for fifty years, black elected officials have been going to a Congress with this all-of-the-above request, and for fifty years they’ve been coming back with money for one of the above—law enforcement and law enforcement only.

Chapter 16: Locking Up Our Own argues that “mass incarceration is the result of small, distinct steps, each of whose significance becomes more apparent over time, and only when considered in light of later events.” If that is the case, can we take steps to reverse the most pernicious consequences of this system?

Forman Jr.: Yes. We can elect progressive prosecutors, fund public defenders, invest in prison education, end mandatory minimums, reject felon disenfranchisement, and begin hiring returning citizens. And that’s just a start!

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.