Da-vid, Da-vid Crockett!

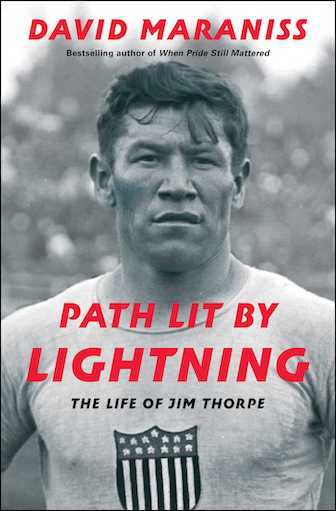

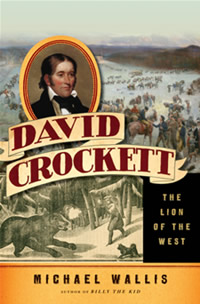

Michael Wallis demythologizes Tennessee’s greatest folk hero

Even if they don’t know all the lyrics, most Americans know the opening lines of The Ballad of Davy Crockett, the Disney-originated hit tune of the 1950s. In fact, what most people know about this country’s most famous frontiersman begins and ends with the Disney version of Crockett’s extraordinary life. Based on the myth-busting facts presented in Michael Wallis’s new biography of Crockett, the lines in the song should have been “Born on a riverbank in Tennessee,” “Killed him a bar when he was in his teens,” and “Da-vid, Da-vid Crockett, The Lion of the West.” As for the coonskin-cap image, it would also have to go: he wore one only occasionally, after his legend had grown and people expected backwoods clothing. And don’t even think of calling the great man Davy—he was always David.

Wallis’s book, David Crockett: The Lion of the West, is full of the kind of information that every Tennessean should know but has likely never learned—including, for example, the fact that Crockett was an adventurer, patriot, and politician who used his fame to oppose the policies of Tennessee’s other larger-than-life personality, Andrew Jackson. Crockett was a complex man given to strong drink and an even stronger sense of honor, and by the end of his life he was fighting for control of his own legend.

In the introduction to David Crockett, Wallis admits to a certain bias toward his subject, one that originated in the 1950s when, like millions of kids, he sported a coonskin cap and sang the ballad while he and his friends pretended to take on the Mexican army at the Alamo. Indeed, the legend propagated by Walt Disney’s three made-for-TV movies permeated society to the point that, as Wallis writes, “[w]ithin only months of the series premier, more than $100 million was spent on at least three thousand different Crockett items, including pajamas, lunch boxes, underwear, comics, books, moccasins, toothbrushes, games, clothing, toy rifles, sleds, and curtains.” Too bad Crockett was long dead by that time—he spent most of his life in debt and could have used the royalties.

In the introduction to David Crockett, Wallis admits to a certain bias toward his subject, one that originated in the 1950s when, like millions of kids, he sported a coonskin cap and sang the ballad while he and his friends pretended to take on the Mexican army at the Alamo. Indeed, the legend propagated by Walt Disney’s three made-for-TV movies permeated society to the point that, as Wallis writes, “[w]ithin only months of the series premier, more than $100 million was spent on at least three thousand different Crockett items, including pajamas, lunch boxes, underwear, comics, books, moccasins, toothbrushes, games, clothing, toy rifles, sleds, and curtains.” Too bad Crockett was long dead by that time—he spent most of his life in debt and could have used the royalties.

The ballad was correct about some things, however. For example, Crockett was Tennessee through-and-through. Born in the eastern portion before statehood, he gradually migrated west with the frontier, homesteading in Middle and finally in West Tennessee, where he staked a claim in Obion County, known as “the land of the shakes” after the giant 1812 earthquake. Although he made forays to the south to fight Indians and later to Washington to fight Jackson’s Indian-removal policy, he traveled little outside his home state until the end, when Texas beckoned with a promise of an even greater frontier. But though he stayed mostly in Tennessee, Crockett was no homebody. A neighbor once described him as “itchy footed,” a fact his second wife learned the hard way when, as Wallis relates, “David surprised his new bride with news of a honeymoon. The only problem was that Elizabeth was not invited to come along.” Crockett headed off hunting again, a pastime at which he excelled and that brought much-needed income.

Crockett himself gets to speak in this accessible biography, through quotations Wallis gleaned from Crockett’s autobiography and letters. In those words are found a man of colorful language and great depth of feeling. Only a callous reader will not be moved when the frontiersman describes an unrequited first love by writing, “[W]hen I think of saying anything to her, my heart would begin to flutter like a duck in a puddle; and if I tried to outdo it and speak, it would get right smack up in my throat, and choak me like a cold potatoe.” Such emotion paid off during his political career, in battles over land policies and the central bank. “Crockett,” writes Wallis, “defined what it meant to be a populist—an advocate for the rights and interests of ordinary people.” Elected twice to the state legislature and three times to Congress, Crockett never gave up his principles, even though sticking to them ultimately cost him his seat.

Crockett himself gets to speak in this accessible biography, through quotations Wallis gleaned from Crockett’s autobiography and letters. In those words are found a man of colorful language and great depth of feeling. Only a callous reader will not be moved when the frontiersman describes an unrequited first love by writing, “[W]hen I think of saying anything to her, my heart would begin to flutter like a duck in a puddle; and if I tried to outdo it and speak, it would get right smack up in my throat, and choak me like a cold potatoe.” Such emotion paid off during his political career, in battles over land policies and the central bank. “Crockett,” writes Wallis, “defined what it meant to be a populist—an advocate for the rights and interests of ordinary people.” Elected twice to the state legislature and three times to Congress, Crockett never gave up his principles, even though sticking to them ultimately cost him his seat.

During his time in Washington, Crockett’s life story was appropriated by others who sought to profit by exaggerating his exploits and mannerisms. A popular and sensationalized play titled “The Lion of the West” gave him his unofficial moniker and convinced him that he needed to regain control of his life by writing his autobiography. But even as he toured the east to promote his book, Crockett played up his frontier life for political effect. His fierce reputation always preceded him, and while visiting Peale’s Museum of Curiosities and Freaks in Philadelphia, he viewed the menagerie that included, notes Wallis, “an assortment of live rattlesnakes, tigers, and, much to Crockett’s delight, bears. The curators breathed collective sighs of relief when assured their famous guest was not armed.”

In David Crockett, as he has done previously with subjects as varied as Billy the Kid and Route 66, Wallis provides a fresh view of a subject near and dear to the hearts of Americans, an inspiration to several generations. Crockett’s autobiography influenced Mark Twain’s writing style, and, Wallis claims, “Abraham Lincoln was yet another historical figure who fell under the spell of the mythical Crockett.” Lincoln, too, “admired Crockett, a man, like himself, who grew up in poverty and became a national icon.” Such is the power of myth when wrapped around the core of an exceptional, real human being. King of the Wild Frontier, indeed.

Michael Wallis will discuss David Crockett at 7 p.m. on May 18 at Barnes & Noble Booksellers in Brentwood.