Deconstructing a Dog

Bronwen Dickey talks with Chapter 16 about Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on August 8, 2016.

***

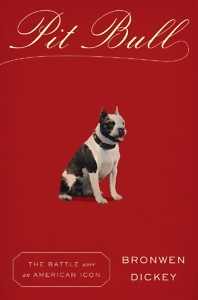

Are pit bulls genetically programmed killing machines, so innately vicious they’re a threat to public safety? Or are they actually sweet, loving “nanny dogs,” unfairly maligned because of their sad history of abuse at the hands of humans? Whether you’re the adoring owner of a pittie or a person who thinks pit-bull bans make perfect sense, you are likely to find some of your assumptions overturned by Bronwen Dickey’s Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon. Dickey sifts through a great deal of history, science, and popular culture to uncover the truth about the dogs and the source of our extreme ideas about them.

The term “pit bull” is generally used to refer to several established breeds, including the American pit bull terrier and the American Staffordshire terrier, but it has also become a catch-all term for any dog of medium size with a blocky head and a short, smooth coat. While it’s true that pit bulls have historically been bred to be “game” fighters, Dickey provides a quick genetics lesson to make a convincing case that this history tells us nothing definite about the behavioral tendencies of today’s family pets. She also demonstrates that the pit-bull designation is used so loosely it’s impossible to know how many serious attacks are actually committed by dogs with a fighting heritage. The widespread belief that pit bulls are exceptionally dangerous encourages people to label almost any aggressive mutt a pit bull.

The complex origin of that belief in “killer dogs” is the real subject of Pit Bull, and Dickey does a fascinating job of tracing the animals’ evolving reputation. They were always admired in some quarters for their plucky eagerness to please, though the popular belief that they were once called “nanny dogs” is not true. They were also often disparaged as ill-bred, coarse dogs of the poor and working class. The idea that they are genetically warped killers is a recent myth created by a cocktail of bad science, misguided animal advocacy, and media sensationalism about the supposedly growing popularity of dogfighting, especially among young black men. The dogs have been swept up in our racially charged hysteria about urban crime, according to Dickey, and our irrational fear of the dogs is fueled at least in part by irrational fear of the people who own them.

Pit Bull contains many heartbreaking stories of abusive or tragic encounters between people and dogs, but Dickey navigates this difficult material with grace, and she depicts some unforgettable characters in the process, including a notorious nineteenth-century dogfighting promoter and a controversial modern-day breeder who says, “I look to these dogs for how I want to live my life.” Her superb writing and meticulous research have garnered glowing reviews, but the book has also met an ugly backlash from the small coterie of fierce anti-pit bull crusaders. These activists seem to have targeted Dickey with particular zeal, trolling her on social media and engaging in extremely nasty personal attacks—ironically supporting her conclusion that there is more unreasoning hatred than sound evidence behind the condemnation of pit bulls.

Dickey is a journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Slate, Popular Mechanics, and Garden & Gun, and she’s a contributing editor at The Oxford American. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You make a convincing case that our exaggerated fear of pit bulls has been largely fed by race and class prejudices. Do you think redeeming the dogs’ reputation can be a small step toward breaking down those prejudices?

Bronwen Dickey: I hope so. My main goal in writing the book was to provide readers with a set of critical thinking skills that they could apply to other scientific “controversies” and to other stereotypes, whether they be racial, cultural, or class-oriented. While I am in no way equating dog-breed stereotypes with other forms of prejudice (the difference in moral scale is enormous, and that should never be forgotten), there are a lot of rhetorical similarities. By using pit bulls as a small example, I hope that people will be inspired to ask more questions when presented with scientific truth-claims, “official“ statistics, and other statements of “fact” that may or may not be accurate.

Chapter 16: Breed-specific legislation seems to be on the decline in the U.S., but it still exists in many other countries, including Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. How hopeful are you that we’ll see a global eradication of these laws?

Chapter 16: Breed-specific legislation seems to be on the decline in the U.S., but it still exists in many other countries, including Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. How hopeful are you that we’ll see a global eradication of these laws?

Dickey: More often than not, breed bans are enacted when cynical politicians want to give the illusion of “cracking down” on a group of people perceived as being “dangerous” without actually having to do the hard work of improving the lives of their constituents. Studies conducted in England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Germany, Italy, and Canada have all come to the conclusion that these laws do nothing to improve public safety, yet they still persist in places where elected officials can whip voters into a state of fear. As the science grows more robust, I think that people will see these tactics for what they are and reject them, in the U.S. and around the world.

Chapter 16: Pit Bull argues that dogs are overall remarkably safe companions, and yet no dog should be considered incapable of doing harm—even very serious harm—because that is simply in the nature of the animal. Is the current trend toward treating dogs like furry children interfering with a realistic understanding of them?

Dickey: I think so. On the one hand, we as a society have made tremendous strides in how we treat animals. A hundred years ago, a dog that lived inside the house was considered rare, and now the opposite is true. Veterinary medicine and the study of animal behavior have advanced in leaps and bounds over the past few decades, as well. Dogs are a bigger part of family life than they ever have been. All of that is wonderful! But when the pendulum swings so far in the opposite direction that we forget that dogs, as strong, intelligent animals, have their own needs and impulses, that can be a serious problem for everyone. By no means should we fear dogs—they are incredibly resilient, tolerant creatures—but we owe it to them to respect their limits.

Chapter 16: What are some specific legal or cultural changes you’d like to see in the way we manage dogs?

Dickey: The main change I’d like to see is stiffer penalties for reckless owners who allow their dogs to injure people or other pets. I was shocked at how few dangerous-dog cases were actually prosecuted, and how little recourse there was for victims of bite injuries. That needs to change. I’d also like to see animal-control departments place more of an emphasis on helping pet owners (the majority of whom are not reckless) comply with laws than on punishing people who are doing the best they can.

Chapter 16: The media has helped fuel pit-bull hysteria through sensationalism and careless reporting. How do you, as a journalist, think the press could do a better job with hot-button issues like this one, especially given the market pressures on news outlets?

Dickey: First off, I’d tell any reporter covering a dog-bite or fatality case that all the information he or she gathers on Day One could turn out to be completely wrong by Day Ten. When law-enforcement and animal-control officers finish their investigations months hence, they will often turn up a bunch of stuff that will never make the headlines. So: skepticism is key, especially with something as traumatic and emotional as an animal-related injury or death. Second, I’d beseech the media not to allow sources who are not scientists to make scientific claims. You wouldn’t ask a fireman to explain organic chemistry to the public, so why allow a “man on the street” to expound on genetics or animal behavior? By doing that, you aren’t informing readers; you are misleading them.

Chapter 16: Your research for this book was exhaustive, and it took you into some very ugly aspects of the human-dog relationship. How did that affect your personal feelings about dogs?

Dickey: It gave me tremendous respect and gratitude for how patient the vast majority of them are in 99.99 percent of situations, even in the most extreme cases of abuse and neglect. The incidents that frighten us often tend to occupy the forefront of our minds, and it’s easy to forget how many millions of dogs are living in very difficult circumstances across the country, and still they hardly ever hurt anyone. That’s truly astonishing. I don’t think I would tolerate one thousandth of what the average dog puts up with.

Chapter 16: Seven years is a long time for a writer to be immersed in a single project, and this is your first book. What’s it been like to come to the end of such a big endeavor?

Dickey: No matter how big or small the project is, I am always intensely critical of my own work, and there are always things I wish I could have done better. When I look back on this one, I know that I truly gave it everything I had. Everything I knew how to do, I did, and everything I didn’t know how to do, I figured out. By the end, I was wrung out mentally, emotionally, and even physically—I spent so many hours typing that during the last three or four months, I could no longer sit upright at a desk and had to prop myself up in bed to alleviate the neck and back pain. I don’t recommend that level of obsession to anyone, but I didn’t know any other way to get the job done. First books can be cruel teachers, but my Lord, they are effective ones. Right now I am just glad to have returned to the human race, at least for a bit. I also want to sleep for a hundred years.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.