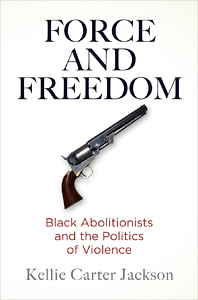

Democracy’s Double-Edged Sword

Kellie Carter Jackson explains how black abolitionists employed the political language of violence

In Force and Freedom, historian Kellie Carter Jackson frames the coming of the Civil War through the agitation of black activists. By employing violence as a political language, these abolitionists compelled national attention and exerted enormous pressure. This short, persuasive book forces readers to see slavery and war through new eyes.

Jackson is the Kanfel Assistant Professor of the Humanities in the Department of Africana Studies at Wellesley College. She earned her B.A. at Howard University and her Ph.D. from Columbia University. She is also the co-editor of Reconsidering Roots: Race, Politics, and Memory. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Jackson is the Kanfel Assistant Professor of the Humanities in the Department of Africana Studies at Wellesley College. She earned her B.A. at Howard University and her Ph.D. from Columbia University. She is also the co-editor of Reconsidering Roots: Race, Politics, and Memory. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Many historians of the abolitionist movement have focused on white leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison, who called for emancipation based on moral persuasion. How did black abolitionists challenge this idea?

Kellie Carter Jackson: In the book, I talk about how “If nonviolent resistance and moral suasion constructed the house that Garrison built, black Americans were merely renters.” Black leaders never fully owned nonresistance principles. Within the movement, black abolitionists, black freedmen, fugitives, and the enslaved were most susceptible to the brunt of proslavery violence. When white anti-abolitionist mobs attacked, it was predominantly black businesses, homes, and churches that were destroyed. Anti-abolitionist mobs regarded any institution in the black community as a target of political, economic, and social competition. Accordingly, black abolitionists sought to protect their property and, most importantly, their lives. They believed in what I call “protective violence” – not merely self-defense, but the collective defense of their communities. By their logic, slavery was created in violence. Slavery was sustained through violence. It seemed logical that slavery might be overthrown only through violence.

Chapter 16: “Violence,” you write, “is the double-edged sword of democracy.” What does this mean in the context of the movement to destroy slavery?

Carter Jackson: Force and Freedom could just as easily be expressed as “force for freedom.” The paradox of using force and violence to bring about freedom and ensure peace is common within our Western political context. The era of revolutions set an early example for understanding violence as both a rhetorical and physical weapon to maintain the status quo, as well as the model to overthrow it. For example, Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” is the quintessential ultimatum; he was using the tenets of democracy to either force freedom or force violence. In the quest for freedom, violence becomes a necessary liberating force when it is the only remaining option. I think that understanding political violence is often about understanding an ideology of last resorts. In many ways, this study is an analysis of “last resorts” among black Americans to ensure freedom and democracy.

Chapter 16: Did black abolitionists draw inspiration from the American Revolution? How about the Haitian Revolution?

Carter Jackson: Yes, black abolitionists used the American Revolution to call out its hypocrisy concerning “We the people.” The Haitian Revolution was their greatest inspiration. The successful overthrow of slavery during the Haitian Revolution supplied the first example of a black revolutionary victory achieved through violence. For black abolitionists, an independent Haiti represented the impossible made possible. The Haitian Revolution, and the slave rebellions more generally, served to illustrate the fact that political violence was a direct and inevitable consequence of slavery and oppression. Black abolitionists offered the Haitian Revolution as a constant reminder of how they could overthrow the institution of slavery in America. For the enslaved and black leadership, violence as a political language meant that Haiti was more than a noun; it was a verb. For black abolitionists, the American and Haitian Revolutions involved more than a set of enlightened principles: Each provided the rationale and means through which to accomplish abolition.

Chapter 16: The book charts the evolution of Frederick Douglass on the subject of political violence. How did he change? Why?

Carter Jackson: I doubt that Douglass ever truly believed in nonviolence. Personally, his fight with Mr. Covey, written about in his narrative, transformed how he understood his manhood and his freedom. Politically, the Fugitive Slave Law pushed him into a public rebuke of moral suasion. In the face of the slave catcher, he believed self-defense was both godly and necessary to prevent capture. When the Civil War began, he actively recruited soldiers and sent two of his sons to war. I think Douglass hoped for nonviolence, but he also understood the power and utility of force.

Chapter 16: In what ways did black activists help to compel the outbreak of the Civil War?

Chapter 16: In what ways did black activists help to compel the outbreak of the Civil War?

Carter Jackson: In a number of ways, black abolitionists made their activism the center of American and even global political discourse. Fugitive slave cases held national attention and caused international disputes, particularly with Canada. Fugitive slaves became public political figures. Black communities developed their own self-protection societies, vigilance committees, and even their own military companies long before the war debuted. Black communities collected money and arms for John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. The greatest financial supporter of Brown was a black woman named Mary Ellen Pleasant. She donated $30,000 to his efforts. Without the contributions of black radicals, Brown’s efforts were stillborn. Black contributions moved the country significantly closer to war and compelled many to consider the crux of the conflict: slavery as warfare against black humanity. I argue that Lincoln was inadvertently presiding over a black war of emancipation.

Chapter 16: Ultimately, Force and Freedom raises enduring questions about how we write history. Why have black abolitionists resided on the periphery of scholarship about the subject? How does the movement look different when we put African Americans at its center?

Carter Jackson: In 1969, historian Benjamin Quarles published Black Abolitionists. Quarles argues that while some white abolitionists would have “never consciously borrowed anything from the South,” many valued the “ego-soothing role of exclusivity thrust upon them by the supporters of slavery.” In Antebellum and Civil War history, white supremacy serves as both the villain and the hero. However, black abolitionists were the first abolitionists. Black abolitionists were instrumental as both the subjects and founders of the antislavery movement. Force and Freedom not only reveals why black abolitionists mattered in the antislavery movement, but also charts their broader significance to American history. Black leaders served as the primary catalysts for recruiting white followers to abolitionism and for investing the movement with its dual commitment to ending slavery and ending racism.

I want readers to see black abolitionists as the leaders and foot soldiers of their own movement. I want to place their efforts and their values at the center of the movement. Too much of the abolitionist movement is told through the lens of sympathetic white allies or limited to the narratives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. There are so many black leaders who accomplished incredible feats in the face of insurmountable odds. At the very least, I want readers to learn something new. Equally important, I want readers to be affirmed in what they already know: that black abolitionists’ efforts were central to the abolition of slavery.

[This article originally appeared on November 13, 2019]

Aram Goudsouzian is a professor of history at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.