Double Album, Double World

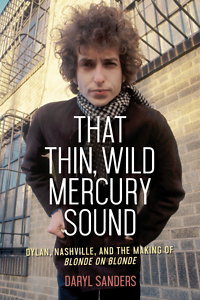

In That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound, Daryl Sanders documents the making of Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde

“The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album,” said Bob Dylan some twelve years after the record’s release. “It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up.” When he came to Nashville in early 1966, Dylan was already two-thirds of the way through his transition from earnest folk singer to avant-garde singer-songwriter and rock star. He had already “gone electric” with Bringing it All Back Home and delivered the quintessential rock anthem of the counter-culture with “Like a Rolling Stone,” the first track of Highway 61 Revisited. But he felt he still had deeper and further to go. With a nudge from his friend Johnny Cash, Dylan came to Nashville and found what he was looking for. In That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound, Nashville music journalist Daryl Sanders pulls the curtain back and allows us to see the wizard at work.

Sanders pays ample tribute to the singular genius of Dylan, but his narrative of the creative process behind Blonde on Blonde gives equal credit to the young studio musicians who instinctively grasped what Dylan was looking for and, thanks to their rich understanding of American roots music and their consummate professionalism, were able to bring it to life.

Sanders pays ample tribute to the singular genius of Dylan, but his narrative of the creative process behind Blonde on Blonde gives equal credit to the young studio musicians who instinctively grasped what Dylan was looking for and, thanks to their rich understanding of American roots music and their consummate professionalism, were able to bring it to life.

“The Blonde on Blonde sessions often have been portrayed as the unlikely musical marriage of New York hipster and southern good ole boys,” Sanders writes. “While it’s true the musicians were primarily native southerners, they also were around Dylan’s age and had been inspired to pick up their instruments by the same music that inspired him. … In many ways, they were more intimate with that music than Dylan was.”

Sanders busts a few myths in his account. Because they served as Dylan’s touring band from 1965 until his motorcycle accident in 1967, the Band—then known as Levon and the Hawks—are often identified with the sound Dylan pioneered on Blonde on Blonde. In reality, Dylan’s first studio efforts with the Hawks in New York were mostly fruitless. “I didn’t know if it was ever gonna be special,” said Robbie Robertson, the Band’s principal songwriter and guitarist. “Just making electric folk music wasn’t enough, it needed to be much more violent than that, and I didn’t know whether he would ever get it.”

Dylan was no less disenchanted. “I mean, in like ten recording sessions, man, we didn’t get one song,” Dylan said. “It was the band. But you see, I didn’t know that. I didn’t want to think that.” Resigned, Dylan followed the suggestions of Cash and producer Bob Johnston to record in Nashville, where Columbia Records’ crew of young studio musicians conjured what the legendary Band could not.

Dylan was no less disenchanted. “I mean, in like ten recording sessions, man, we didn’t get one song,” Dylan said. “It was the band. But you see, I didn’t know that. I didn’t want to think that.” Resigned, Dylan followed the suggestions of Cash and producer Bob Johnston to record in Nashville, where Columbia Records’ crew of young studio musicians conjured what the legendary Band could not.

It may seem faintly ironic that Dylan had to ditch a group revered for its authenticity and replace them with a revolving cast of studio musicians in a town known for slick commercial production, but as Sanders ably illustrates, this irony results from a deep misunderstanding of the players in Nashville’s recording studios. Sanders’s description of Dylan’s collaboration with the Nashville Cats is both mythic and comical. The young studio musicians spent countless hours idling in polite bewilderment while Dylan tinkered with the lyrics and structure of the songs, and then wearily worked through the night to bring the songs to life, such that they seemed to have sprouted like magic mushrooms in the darkness.

Sanders pays just due to the development of Dylan’s lyrical sensibility—the influence of Modernist, French Symbolist, and Beat poetry on his increasingly abstract style, for instance. And he clarifies both the profound significance of the album on the rock-music landscape and, perhaps more significantly, its importance to a generation of young singer-songwriters soon to make their mark—the likes of Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, and Tom Petty—and, in Nashville, Kris Kristofferson, Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Steve Earle.

But That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is principally about how the individual artist must depend on similarly gifted collaborators to bring an artistic vision to life. Like Maxwell Perkins editing and mentoring the young Thomas Wolfe and F. Scott Fitzgerald, producer Bob Johnston enabled Dylan to find his own way. The Nashville Cats felt Dylan’s needs and sensed where he wanted to lead them because he was drawing directly from the same well from which they sprang.

That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is essential to Dylanologists, but it should also be useful to anyone curious about the way records get made, and, especially, to aspiring performing songwriters yearning to understand what it takes to transform great songs into legendary recordings.

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.