Earning the Respect of the Materials

Clarksville artist Billy Renkl illustrates his first children’s book

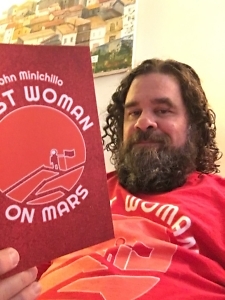

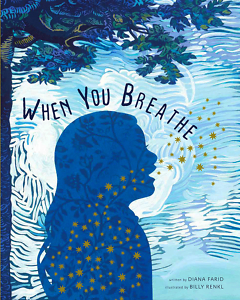

Artist Billy Renkl’s exquisite layered collage pieces may very well take your breath away, so it’s fitting that his debut as a children’s book illustrator focuses entirely on breath. Diana Farid’s When You Breathe is a meditation on respiration, a lyrical look at how it takes merely “seconds for a piece of the sky to fill your heart.”

For decades, Renkl has worked as a fine artist, participating in countless solo and group exhibitions. As an illustrator, he has done book covers — including the cover of and interior artwork for last year’s Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss, written by his sister Margaret Renkl — as well as editorial work for magazines and newspapers. And for over 30 years, he has taught drawing and illustration at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville.

He’s especially fond of vintage and antique paper, which he uses to create his richly colored and detailed collages. It “carries its history with it,” as he writes at his website, in a way that he finds moving.

Chapter 16 talked via email with Renkl about his first picture book, what it’s been like to teach during a pandemic, and more.

Chapter 16: Congratulations on your debut picture book! You are a fine artist by day. What were the joys and/or challenges of working in the 32-page picture book format?

Billy Renkl: Thanks! I spend a lot of time talking with my own students about how those aren’t mutually exclusive categories. Really, I’m pretty sure I don’t ever have any original ideas anyway. They all come from some other great mind — Rilke, or Shakespeare, or Sonya Clark. I get a remarkable newsletter called The Listening World. It’s from an organization called Unrestricted Interest. The Listening World celebrates the work of autistic, non-speaking, and other neurodivergent poets, and I learn something new about how language works every single time it comes to my inbox.

That’s to say that I just don’t see a difference in trying to embody the language knocking around in my own head (as a fine artist) and the language that came from Diana’s fruitful mind. I like giving ideas form; I don’t much care where the ideas come from. As for the multiple-page format? There are 13 illustrations in When You Breathe, and that doesn’t seem so different from planning an exhibition that will have 13 works on the gallery walls. I had to learn a lot about pacing the images, but I had a terrific art director at Cameron, Melissa Greenberg, who coached me through that. (I still have plenty to learn about that, of course, and I’ll count on other heroic art directors to pick up where she left off.)

Chapter 16: This is a text with more than one moment of figurative language (such as “breath fills the upside-down tree inside your rising chest”). Which spread was the most fun to visually bring to life?

Renkl: When someone says, “Let me be clear,” I mostly think they’re embarking on a fool’s errand — language just isn’t all that clear. Setting out to say something in a beautiful way, though, gets my attention every time. My students sometimes want to pin down what a work means: Is the light that streams in from the left in Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance simply a Netherlandish morning, or is it spiritual insight? My answer, of course, is “Yes.” (That’s smug shorthand for “Happily, we don’t have to pick. It can be both, or either, or more.”) And anyway, it’s so very beautiful. There’s no question about that.

In terms of figurative language, I love that trope of the lungs as branches, woven all through the book. That’s really the visual crux of the illustrations. I so much enjoyed building those lungs out of a 16th-century wood engraving of spurge laurel. (I tried other plants, but the spurge laurel was clearly best.) I think of metaphors as being multi-directional. To say “My love is like a red, red rose” tells us something about love and something else about roses. Diana’s hymn is about breathing, but it also implies such beautiful things about trees: respiration and photosynthesis, lungs and leaves. And I sure enjoyed thinking about the branching of the bronchi in botanical terms.

Chapter 16: You have said before: “I like to think of myself as cooperating with the images I use, the way an after-school program might make use of retired volunteers.” When you first read this manuscript, did you have an immediate vision for things like the primary color palette, which kinds of papers you would want to use to build the illustrations, how you would build the compositions, etc.?

Chapter 16: You have said before: “I like to think of myself as cooperating with the images I use, the way an after-school program might make use of retired volunteers.” When you first read this manuscript, did you have an immediate vision for things like the primary color palette, which kinds of papers you would want to use to build the illustrations, how you would build the compositions, etc.?

Renkl: Even though there are tens of thousands of pieces of paper in my studio (it might be a little bit of a fire hazard), I sort of know what’s there. When I start a project, either client-based or not, I start with what I have on hand. I do often need to supplement what’s in inventory as the project gets moving, but I generally anchor the project in what I have already gathered to me.

With When You Breathe, I knew pretty much right off that I wanted to use cyanotypes. A cyanotype solution (potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate) can be painted on almost any paper and uses sunlight to make a lovely Prussian blue image. The process, invented by an astronomer (!) in the 1840s, just seemed so perfect for this text — air and sunlight and the chemistry of the cosmos, conspiring to make such a splendid blue! The text was also so tender. I used a lot of vintage postcards from the beginning of the 20th century, all tokens of love with backs filled with good wishes. The flowers and leaves in the trees and in the body are all from those chromolithographed greeting cards. I think of all of those tender sentiments as being bound up in the book now.

The painted skies are a big part of the visual language of the book for me. They look like conventional paintings, but under the paint are cyanotypes made from greatly enlarged inconsequential sections of sky from antique landscape engravings. Each of those engravings is about something considered important — a view of a German city, or a New Testament story, or a classical myth — and I imagine that, for the hundreds of years those prints have existed, no one has paid much attention to the skies. They were just the background. Likewise, no one thinks much about breathing (well, until recently, and now that’s all we think about!). I believed that making those very skies, the unobtrusive air made visible, into a crucial aspect of the illustrations was in the spirit of the text.

Chapter 16: You’ve also said before that you find a lot of paper for your artwork at junk stores and flea markets. Has the pandemic cramped your style in terms of finding artistic materials to work with?

Renkl: When I was young and always broke, junk stores and flea markets were essential to my studio life. I guess I even took some pride in rescuing something that was on its way to the city dump — and making it in some way valuable again. At that time, much of my work was specifically a response to the papers that I found. I get to be more intentional now and often seek out a particular image or material because it feels necessary to my idea. There is nothing romantic about this at all, but lately I find much of what I need on eBay. The global pandemic didn’t change much for me in that regard.

I have a fairly rigid rule that I’ll only place the minimum bid. If someone else is willing to pay more than the opening bid, then they value it for what it is now, and I’ll honor that. I’m plagued by the suspicion that whatever that cool piece of paper is already is better than what I’ll do with it. One of my heroes is a brilliant artist named Dario Robleto. He spoke at Austin Peay a few years ago and told us that on his studio wall is written the question, “What do I need to do to earn the respect of these materials?” Oh, man, I might never recover from hearing him say that.

Chapter 16: Speaking of COVID-19, did you have to teach virtually at Austin Peay for some time this year? What has it been like to be someone who teaches drawing and illustration during a fraught, socially distanced time?

Chapter 16: Speaking of COVID-19, did you have to teach virtually at Austin Peay for some time this year? What has it been like to be someone who teaches drawing and illustration during a fraught, socially distanced time?

Renkl: I used to suffer from the noble misapprehension that I taught for the joy of seeing students make good work. It turns out that what I really teach for is eye contact. Zoom fails miserably at eye contact.

We moved online during spring break last semester. Students said goodbye on a Friday, expecting us all to be together again after a little more than a week, and then they never came back. Even graduation was cancelled. This semester I’m at least teaching hybrid courses. I see some students once a week, but the rest of the time I am staring at the screen — Zoom meetings, Zoom classes, Zoom critiques, and a daily tsunami of emails, which are supposed to take the place of everything from pleasant, collegial interaction to intense and fraught debate over the nature of meaning. Email just isn’t up to any of that. My students are making very good work this semester, but the noble pursuit of an education is broader and deeper than solving the assignments I give in a skillful way. I’m still trying to figure out how to manage the rest of it: how to be a conscientious witness to their creative lives; how to encourage good work, while being clear that their worth has nothing to do with their artwork; that their modest intentions for an artwork are often eclipsed by what their artwork actually does — things like that.

Chapter 16: You have done a good deal of editorial illustration work and book cover work for a wide array of clients. What was it like to provide the illustrations and cover art for your own sister’s book — Late Migrations by Margaret Renkl — given that it’s a book about your own family?

Renkl: Just between you and me, I’m not so sure it makes sense to think of that book as about my family. It’s about Margaret’s family. One of the great gifts of that book was realizing with a start, with amazement, that even though we were only 18 months apart in age, our experience of growing up in our house was so very different. I don’t know how to account for that. Is 18 months enough? Birth order? Gender? Temperament? The fact that I was, it turns out, a completely peculiar and self-absorbed kid?

I read much of Margaret’s book with wonder. What a delight to learn, that after all these years of assuming that the three of us had had similar experiences, that there was another rich, complicated, resonant way to think about the life of our family. Margaret’s book was an occasion to talk with her and our sister Lori about the ways our understanding of our family dynamics were different (though in every case suffused with love). That was astonishing, really. Margaret was fiercely attuned to our mother’s bouts of depression; I was not especially aware of them. Your question was about Margaret’s book, but can I make this about me? Maybe what I learned is that I was astonishingly unaware of things she was acutely experiencing. This might explain why she ended up being a writer and I did not.

Chapter 16: Working on any new projects that are particularly inspiring?

Renkl: If I’m working on it, I suppose it goes without saying that it’s inspiring! My current long-term project in the studio is a set of works that tracks my experience of the hours of the day. It’s sort of a Book of Hours (a Medieval prayer book that functioned as a way to sanctify the day for someone who didn’t live in a cloister), but mine is secular. And in place of prayer, it employs attention and my own lived experience (which is, perhaps, best understood as a kind of prayer). Also, it isn’t a book — just 24 related artworks.

I do have some ideas for picture books that are gestating, but I thought I’d figure out how this one managed out in the world before I turned to them with any focus. And some day I’d like to make an alphabet book.

Julie Danielson, co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and The Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro and blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.