Existing Within Each Moment

Wei Tchou’s experimental memoir speaks several languages at once

“I’ve spent my entire life translating myself into a language the outside world speaks,” laments Wei Tchou, familiar to a broader audience for her articles about food and drinks for such publications as The New York Times and The New Yorker. Tchou’s new memoir, Little Seed, is, on the surface, precisely such an attempt at self-translation, an effort to prove to the world “that I am here in sentences and paragraphs and words.” But it is a deeply unconventional one, in which the author comes to us speaking, indeed, several languages at once.

Little Seed creatively interweaves the author’s personal history — her growing up, the daughter of Shanghainese immigrants, in an “Appalachian enclave in Tennessee,” her undergraduate years at the University of North Carolina, the life she creates for herself as a writer in New York — with forays into, of all things, the natural history of ferns. Rather than merely making herself intelligible to her readers, Tchou actively challenges them, with often lengthy digressions on ferns, their beauty, their resilience, and their evocative names, which roll off the tongue like a list of ingredients for a witch’s brew: maidenhairs, glassworts, spleenworts, moonworts, adder’s tongues, and rabbit’s foot.

Little Seed creatively interweaves the author’s personal history — her growing up, the daughter of Shanghainese immigrants, in an “Appalachian enclave in Tennessee,” her undergraduate years at the University of North Carolina, the life she creates for herself as a writer in New York — with forays into, of all things, the natural history of ferns. Rather than merely making herself intelligible to her readers, Tchou actively challenges them, with often lengthy digressions on ferns, their beauty, their resilience, and their evocative names, which roll off the tongue like a list of ingredients for a witch’s brew: maidenhairs, glassworts, spleenworts, moonworts, adder’s tongues, and rabbit’s foot.

Ferns, for the author, represent an alternate realm of overwhelming beauty, exuberant diversity, and infinite magic. A world fundamentally different, then, from the one in which young Wei Tchou, who calls herself “Little Seed” throughout most of the book, has to learn how to function, where her best chance of survival is to make herself look, as much as she can, like everyone else. In that world, she is “a little seed that is just blowing around,” forever frustrated in her search for the blend of safety and freedom her actual Chinese name (Wei Tchou) signifies but her family can’t or won’t give her. The mental toll of such an unmoored life becomes painfully evident in her brother’s psychotic breakdown and in the author’s own traumatic relationship with her journalism instructor at UNC, appropriately called “the Spider,” an inveterate mansplainer and master of abusive manipulation.

No wonder that Little Seed feels drawn to the quieter charms of the fern world. Reproducing through spores, not seeds, ferns resist the traits humans project onto them. And they are supremely adaptable: writing about the iridescent ferns that thrive in the shadows of the rainforest where only little light will reach them, Tchou marvels at their ability “to grow so lushly given so little.” Tchou’s effortlessly poetic descriptions of ferns reveal the love she feels for them: maidenheads have pinnules (leaflets) that look like “heavily lashed eyelids or folding fans,” while the brackens, their sturdier relatives, familiar from fields, pastures, and parks, sport leathery fronds that, once the spores have come in, shine as if they had been embroidered with gold.

To cope with the void left by her brother’s mental crisis, the author, switching to first-person narration, travels to Mexico, where she heard she might find a “density of ferns.” She is not disappointed. Somewhere near Oaxaca, we see her hiking through a jungle stocked with all kinds of ferns, ferns “in the shape of clover, rising up on tall spindly legs,” ferns shaped like “talons padding around a mossy thin tree,” ferns “glowing like phosphor.” Here she finally discovers why these plants, both archaic and brand new, have so consistently given her calm and peace: “the feeling of wholeness, knowing that this place stood as it did and had always been so.” She picks up a translucent fern growing under a boulder and twirls it in the air to see how the sun filters through it — illuminating the leaves as if from the inside, making them shimmer in shades from emerald green to dark purple. And that just so happens to be an excellent description of Tchou’s exquisitely textured prose, too.

To cope with the void left by her brother’s mental crisis, the author, switching to first-person narration, travels to Mexico, where she heard she might find a “density of ferns.” She is not disappointed. Somewhere near Oaxaca, we see her hiking through a jungle stocked with all kinds of ferns, ferns “in the shape of clover, rising up on tall spindly legs,” ferns shaped like “talons padding around a mossy thin tree,” ferns “glowing like phosphor.” Here she finally discovers why these plants, both archaic and brand new, have so consistently given her calm and peace: “the feeling of wholeness, knowing that this place stood as it did and had always been so.” She picks up a translucent fern growing under a boulder and twirls it in the air to see how the sun filters through it — illuminating the leaves as if from the inside, making them shimmer in shades from emerald green to dark purple. And that just so happens to be an excellent description of Tchou’s exquisitely textured prose, too.

The therapeutic effect of the Mexico visit is immediately evident in the book’s “Epilogue,” in which the author accompanies her parents to Shanghai, “the biggest city that humans ever built,” a place she is and isn’t from. On the eve of a pandemic that will change everyone’s lives forever, she has already turned her own life around, having learned to exist “only within each day, within each moment.” As she does everywhere, she finds a fern she likes in her father’s ancestral village, a little thing hiding under some steps in a cousin’s courtyard. Wrapping it gently in a piece of paper, she takes it home with her, wherever that might be. A fitting ending for an extraordinary first book.

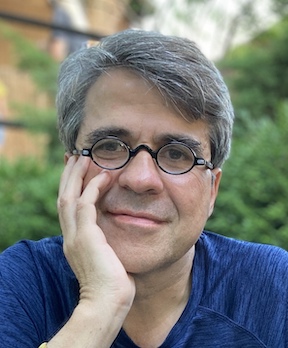

Christoph Irmscher lives in Bloomington, Indiana, where he teaches at Indiana University. He is a biographer and literary critic, known especially for The Poetics of Natural History and his biographies of Louis Agassiz and Max Eastman. He serves on the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle and writes reviews for the book section of The Wall Street Journal and The Art Newspaper.