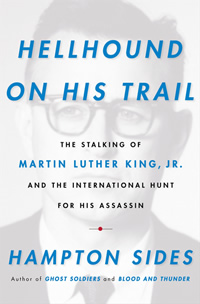

Focusing on the "Story" in History

Hampton Sides’s account of the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. reads like a James Ellroy novel

James Earl Ray was, in every detail, a character ripped from film noir. Completely unrooted, he escaped from prison only to bounce from Mexico to Los Angeles to Atlanta to, finally, Memphis. He was in search of—what? Not love or money. At times he wanted to direct porn, at others to tend bar. Completely amoral, he went through life as a small-time crook, only to commit one of the most infamous murders of the twentieth century.

Ray’s story is the heart of Hellhound on His Trail, Hampton Sides’s account of the events surrounding the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. The book is both gripping and frustrating. Readers new to the subject, or just looking for a good story, will find it hard to put down, but anyone already familiar with King’s murder will wonder why Sides decided to retell this oft-repeated tale.

Sides starts with Ray’s 1967 escape from a Missouri prison, locked in a fetal position under the false bottom of a breadbox, a feat he had spent months training for. Ray was well-known around the yard as a weirdo and a loner, so the sight of him practicing yoga—the better to prepare himself for sustained stress positions—didn’t strike anyone as odd.

Once outside, Ray drifted, eventually landing in Puerto Vallarta, where he took up Polaroid photography and shacked up with a local prostitute. A few months later, he was in Los Angeles, attending bartender school and doing volunteer work for George Wallace’s presidential campaign. He made friends but kept them distant; he posed for photos but glanced away when the shutter clicked.

Once outside, Ray drifted, eventually landing in Puerto Vallarta, where he took up Polaroid photography and shacked up with a local prostitute. A few months later, he was in Los Angeles, attending bartender school and doing volunteer work for George Wallace’s presidential campaign. He made friends but kept them distant; he posed for photos but glanced away when the shutter clicked.

Ray eventually drifted back east, to Atlanta, King’s hometown. He began to follow King’s movements, “stalking” him, in Sides’s words. On the way to Atlanta, he stopped overnight in Selma—perhaps, Sides speculates, because King was scheduled to make a stop there. “He wanted to take note of the style in which the minister traveled, his habits of movement, the presence or absence of bodyguards or police details,” he writes. A few days later, learning that his adversary was in Memphis, Ray drove his white Mustang across Alabama and Mississippi, picking up a rifle along the way. On the morning of April 4, he rented a room in a shaggy SRO only a few hundred feet from King’s room at the Lorraine Motel.

In the confusion following the assassination that evening, Ray was able to escape town easily, though not without leaving a wealth of clues behind. He drove back to Atlanta, then took a bus to Canada. His ultimate destination, Sides speculates, was Rhodesia, where he had heard he could work as a mercenary for the faltering white supremacist government. After weeks spent waiting for a fake passport, Ray flew to London, then Portugal, then back to London, where he was finally apprehended.

Hellhound has already won comparisons to James Ellroy crime novels, and it is definitely a great narrative historical account. Sides toys with, but never crosses, the line between drama and melodrama, his sentences built with meticulous care to compel, but never push, the reader onward. Like certain songs and film plots, there are some stories in history—George Washington biographies, D-Day—that can be taken up again and again, stories so captivating that all it takes is a good writer to give them new life. King’s murder is one of them.

Sides, a Memphis native best known for Ghost Soldiers, about a World War II rescue mission, wants nothing more than to spin a good yarn. It’s far from an academic account—as Sides notes in his introduction, his writerly muse is Shelby Foote, who told him he had “employed the novelist’s methods without his license” in writing his acclaimed Civil War trilogy. Sides does the same—this is a story as much as a history.

Sides, a Memphis native best known for Ghost Soldiers, about a World War II rescue mission, wants nothing more than to spin a good yarn. It’s far from an academic account—as Sides notes in his introduction, his writerly muse is Shelby Foote, who told him he had “employed the novelist’s methods without his license” in writing his acclaimed Civil War trilogy. Sides does the same—this is a story as much as a history.

But is it enough simply to tell a good tale? Sides’s book comes only a decade after Killing the Dream, Gerald Posner’s own thorough account of Ray’s progress toward Memphis. Posner, a lawyer-turned-journalist, approaches his task with a prosecutor’s zeal, meticulously building the case against Ray and disposing of the myriad conspiracy theories that have piled up in the ensuing decades.

Sides ignores the theories. Perhaps this is a wise decision; that way madness lies. Yet these conspiracy theories are such an integral part of American history, and the fact that King’s family themselves believe Ray was innocent is reason enough to discuss them, if only to show why they’re bunk.

Posner also considers motive. How could a guy like Ray pull the trigger? He was a white supremacist, yes. But other than volunteering for Wallace, there’s no evidence that his racism was particularly virulent. Ray was a small-time crook, but never violent—in fact, he had little experience with firearms. Posner argues that it was a mix of racism, self-aggrandizement, and a good-old American dream of fame, leavened with a few heaping tablespoons of psychosis, that led him to kill King.

Sides, though he points toward a similar profile, ultimately leaves his Ray a mystery. Like the century’s great existentialist heroes—Meursault in The Stranger, Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause—in Sides’s telling, Ray’s motives are inscrutable, his thoughts unknowable.

In a way, this makes for better reading. Sides never steps out of the narrative; the pages turn as if on their own accord. By avoiding the tricky questions, Sides is able to give readers a great story about one of America’s great tragedies. But to do so, he punts on the details of its history.

Hampton Sides will give a free public reading at Memphis University School on April 27 at 7 p.m. Davis-Kidd Booksellers will sell signed copies, and a percentage of book sales will go back to a partner of the event, the National Civil Rights Museum.