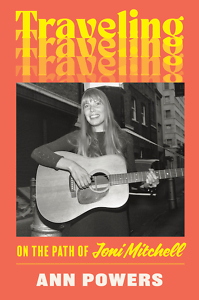

Forging an Autonomous Path

Music critic Ann Powers shows us how Joni Mitchell made her own way

Near the beginning of Ann Powers’ Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell, the NPR music critic tells about standing in her front yard to look at gathering storm clouds when a New York editor called to ask if she’d like to write about the singer-songwriter best known for 1960s folk hits such as “Both Sides Now” and “Big Yellow Taxi.”

Powers told the editor she needed a minute. Seeing herself as “not a biographer, in the usual definition of that term,” she took a walk around the block “to mull over the possibility of entering the Joni congregation” made up of “devotees and scholars” who thought Mitchell could do no wrong. Though taking on the project would complicate her life for a while, she called the editor back to say yes.

As the title implies, Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell is not a traditional biography, nor is it hagiographic. Powers understands that Mitchell, like all of us, has had her ups and downs. The book is more like a road trip, with stops along the way to consider Mitchell’s childhood in Canada, where she grew up as Roberta Joan Anderson, an only child who contracted polio at age 9; her start as a musician in local coffeehouses; an unexpected pregnancy by a man who left her and a brief marriage to Chuck Mitchell, whose name she kept; and on to Los Angeles, where she built the career most of us know.

It’s also about more than Mitchell herself. It’s about the iconic times she lived in, her relationships with other musicians, and “what it means to move in a body gendered female through spaces dominated by men.” A hybrid work that includes interviews, critical analysis, and a little bit of Powers’ own story, it reads like a long conversation with a friend who is telling you what she thinks.

Much of Mitchell’s story has been told before in books such as Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words, a series of interviews the singer did with journalist Malka Marom, published in 2014, and Reckless Daughter, a 2017 biography by David Yaffe. Powers’ book is marked not only by that conversational tone but by the way she weaves in women working in various art forms, including poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, novelist Margaret Atwood, and painter Georgia O’Keeffe. According to Powers, they are all geniuses who had to forge an autonomous path to avoid being swept up in “generic womanhood” during the era when the women’s liberation movement was just beginning to bring greater awareness of sexism.

The most intriguing chapter, to me, was “The Boys,” which is partly about Mitchell’s romantic relationships with David Crosby, Graham Nash, and James Taylor but mostly about gender-power relations in the popular music scene of the 1960s. It was difficult, Powers argues, for even the most talented women not to be subsumed by the role of a male musician’s “old lady” — the popular term for wives and girlfriends. Mitchell had romances, but she avoided being one of the “boys’ girls” whose history “is mostly one of women claiming power that also at least partially erases them.” Largely because of her enormous talent, Mitchell was one of the “free women” who “upset the whole order by doing what they wanted and still demanding respect.” Still, Powers notes, it is odd that no one asks why Crosby, Stills, and Nash, who often sat in her kitchen singing, never asked her to join the band.

Powers doesn’t shy away from troubling incidents in the 1970s, when Mitchell appeared in blackface at a party and on the cover of her album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. Dating a Black man during a fraught period of American race relations, Mitchell had sought to defy the way we categorize one another. “Confronting these episodes forces any Mitchell chronicler to seek insight but resist making excuses,” Powers writes. She does so, problematizing Mitchell’s actions but acknowledging her intent.

Powers doesn’t shy away from troubling incidents in the 1970s, when Mitchell appeared in blackface at a party and on the cover of her album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. Dating a Black man during a fraught period of American race relations, Mitchell had sought to defy the way we categorize one another. “Confronting these episodes forces any Mitchell chronicler to seek insight but resist making excuses,” Powers writes. She does so, problematizing Mitchell’s actions but acknowledging her intent.

Later in the book, Powers explores at length Mitchell’s work in the 1980s and beyond, including the 1991 album Night Ride Home, much of which she wrote with second husband Larry Klein. Again, other genres become part of the story, notably in the song “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” in which Mitchell’s lyrics build on W.B. Yeats’ iconic post-World War I poem, “The Second Coming.” The song also shares a title with Joan Didion’s classic 1968 book of essays, and its lyrics echo Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel Things Fall Apart — strengthening the argument that popular music is too small a container to consider the work of a woman who, in her teens, had found the work of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche a good read. In the 1990s, a resurgence of feminism meant a new generation of female singer-songwriters, including Tori Amos and Natalie Merchant, professed a debt of gratitude to Mitchell.

Near the end, Powers tells us how she met her subject only once, in 2004, at a conference. About to give a panel talk on Mitchell’s album Blue, Powers looked up to see the singer with Kilauren, the daughter she’d placed for adoption at 21 and who had found her in the late 1990s. A newly adoptive mother herself, Powers became emotional when talking about “Little Green,” a song Mitchell had written about Kilauren, whom she had once called Kelly. Having a hard time going on, she heard a voice from the front row — Mitchell’s.

“You can do it!” the singer told her.

Jane Marcellus is a writer whose published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism.