Founding Sailors

Nathaniel Philbrick explains how George Washington—and the French navy—won the American Revolution

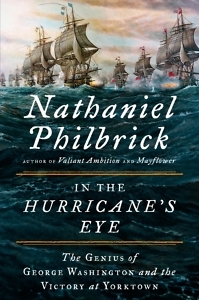

In times of national stress, reading history can be reassuring, a reminder that bad years can be endured and overcome. But it is also inspiring to read about the glories of the past, the great accomplishments in which Americans can take pride. Such a history is Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Hurricane’s Eye: The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown, a book that celebrates the near miracle of the American triumph over Great Britain. It was a victory won at sea as much as on land, a fact often overlooked in the popular images of George Washington riding into battle on his horse, or of the Continental army suffering through the winter at Valley Forge.

Philbrick, whose many honors include a National Book Award for In the Heart of the Sea, completes a Revolutionary War trilogy with In the Hurricane’s Eye, a gripping account of the campaigns of 1781, the year a determined new nation broke the British hold on North America. In this series, Philbrick has followed George Washington from Boston (Bunker Hill) through the treason of Benedict Arnold (Valiant Ambition) and now to the glory of Yorktown, where combined French and American forces vanquished their common foe.

Washington’s military abilities are often overlooked even as he is rightly honored as the father of our country. Though he is regarded as an inspiring leader, he is often disparaged for losing more battles than he won. But Washington was a fast learner who soon mastered military tactics and knew that America would need help to win the war. By 1780 he was looking increasingly to the sea. Philbrick writes, “As Washington understood with a perspicacity that none of his military peers could match, only the intervention of the French navy could achieve the victory the times required.” If only he could get the French to cooperate.

In Philbrick’s account, it was a literal hurricane—actually, three hurricanes—in October 1780 that set the stage for French naval support. One of them, the Great Storm of 1780, killed more than 20,000 people and, as Philbrick notes, convinced the French that “the best place for a navy in the summer and fall was anywhere but the Caribbean.” The next year found the French navy, with some timely financial help from Spain, sailing north against the British. They won two key battles and by late summer of 1781 had effectively blocked the entrance to Chesapeake Bay.

Isolated by the French blockade was a British force commanded by Lord Charles Cornwallis, who had spent most of 1781 chasing Americans through North Carolina, losing a key battle at Guilford Courthouse, where General Nathaneal Greene embarrassed the British. “History has made him synonymous with the defeat at Yorktown,” Philbrick writes, “but Cornwallis’s ultimate undoing was set into motion at 1:30 p.m. on March 15, 1781, when … he ordered his men to charge into Nathaneal Greene’s trap.” The North Carolina campaign, designed to consolidate British gains in the South, collapsed. A desperate Cornwallis removed his army to a small Virginia town near the mouth of the York River. It should have been, with naval support, an easily defensible position.

Isolated by the French blockade was a British force commanded by Lord Charles Cornwallis, who had spent most of 1781 chasing Americans through North Carolina, losing a key battle at Guilford Courthouse, where General Nathaneal Greene embarrassed the British. “History has made him synonymous with the defeat at Yorktown,” Philbrick writes, “but Cornwallis’s ultimate undoing was set into motion at 1:30 p.m. on March 15, 1781, when … he ordered his men to charge into Nathaneal Greene’s trap.” The North Carolina campaign, designed to consolidate British gains in the South, collapsed. A desperate Cornwallis removed his army to a small Virginia town near the mouth of the York River. It should have been, with naval support, an easily defensible position.

When Washington—with his trusted protégé, the Marquis de LaFayette, and General Rochambeau, commander of French forces—arrived in front of Yorktown in September with almost 20,000 men, he could scarcely believe his good fortune. The French navy retained control of Chesapeake Bay, Cornwallis had his back to the water, and Washington immediately ordered a siege. After a series of textbook military maneuvers, including a massive artillery bombardment, the Americans received Cornwallis’s surrender, effectively ending the revolution. “Little short of a standing miracle” was how Washington characterized the victory in his farewell orders to the army.

With In the Hurricane’s Eye, Philbrick strives “to put the sea where it properly belongs: at the center of the story.” He is eminently qualified to do so, being both an accomplished sailor and an author who has written brilliantly on maritime history. That he is also able to bring life and suspense to the land portion of the war makes for a complete and satisfying picture of one of America’s greatest achievements.

He doesn’t ignore some of the failings of the revolution, however. The re-enslavement of many African Americans in the aftermath of the triumph was a tragedy, and Philbrick observes that “Yorktown was the site of a great victory, but it was also where the road to the Civil War began.”

Nevertheless, in throwing off the monarchy Washington and others instilled an ideal of liberty that could not be—has not been—extinguished. A part of that ideal is the notion of a selfless leader. “Washington,” Philbrick writes, “had long since learned that greatness was attained not by insisting on what was right for oneself but by doing what was right for others.” And that is truly inspirational.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than twenty-five years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.