Future Farms

A science writer traveled to the fields and labs where agriculture is changing

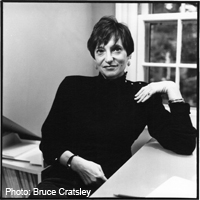

Vanderbilt University Professor Amanda Little delivered the news in her 2019 book The Fate of Food: Our food systems are broken and the climate crisis is rushing them to a conclusion.

If we needed more proof that we have to change our ways, the coronavirus is supplying it, as Little says in her TED talk, “Climate change is becoming a problem you can taste,” which has logged more than a million views. At the outset, she shows pictures of masses of potatoes dumped by Idaho farmers whose markets were shut down by COVID-19, while at the same time thousands of cars waited at a Texas food bank set up to respond to the pandemic.

Surprisingly, though, The Fate of Food — just released in paperback — is upbeat, a source of ingenious solutions and solace in science. Little went to 15 countries and 18 states for her research among farmers, inventors, and adventurous agri-tech investors, and she describes herself as “hell-bent on hope.” The book’s subtitle, “What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World,” telegraphs the message that there are ways to pull back from the brink. (Though she’s devoted to solution-based optimism, she also freely admits to being “a failed vegan and a lapsed vegetarian and a terrible backyard farmer.”)

Little, who teaches journalism in a variety of its forms — science writing, creative nonfiction, the art of blogging, opinion writing — is a Bloomberg contributor and is currently focusing on the ways Black farmers in America were dispossessed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s discriminatory practices. She’s also the founder of Kidizenship, a nonpartisan media platform for tweens and teens who are interested in politics.

And politics, particularly in Washington, D.C., is where our best hopes for change in food production now reside, Little said in a recent conversation with Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: In your book and TED talk, you say you’re optimistic about the future despite the food crisis that climate change is creating, and despite continued climate-crisis denial. Where are the promising research and innovations you describe in The Fate of Food taking hold?

Amanda Little: It is important to note that in 2016 and also 2020, agricultural states overwhelmingly supported President Trump, with the exception of California. So much of the American heartland where agriculture is centered has traditionally voted Republican. Climate is so politically polarized. This focus on a new direction for sustainable agriculture is itself seen as a politically inflected issue.

Climate resilience in agriculture should be a bipartisan issue, and it isn’t yet. I interviewed a lot of farmers, including one in an early chapter who talked about how [farmers] see climate bearing down on their own soil and crops. They say, “Look, things are changing, we’ve seen this … but is it climate change? I don’t know. I’m not a scientist, I’m a farmer.” I heard that over and over. You have to be an optimist if you’re a farmer because you face so many risks. It was always risky, and it’s getting more and more risky. Virtually every food grower I interview talks about drought, heat, flooding, invasive insects, increasing weather volatility. But, [they say] “Do we want to call it climate change?”

Agriculture is one of the single major drivers of climate change as an industry. Fifteen to 20 percent of global greenhouse emissions is related to agriculture, related to food production, a lot from livestock. So it’s a driver of climate change, but climate change is fighting back. You can continue producing pollution sources in electricity or transportation in the face of climate pressure, but you can’t continue producing food. Part of what makes me very hopeful is that there’s so much motivation for food producers to convert from being the problem to being the solution.

We need bold legislation that will incentivize crop producers to take on the practices of conservation agriculture, like cover crops that absorb and sequester carbon in their roots, and soil and no-till practices that, again, let farms become a carbon sequester sink rather than carbon producers.

Farmers need to be paid for that, to take on these practices. It’s beginning to happen, but not on the scale it needs to happen. We need the right policies and incentives that will support farmers. This political divide is significant when we think about when that will happen in agriculture.

Chapter 16: Where are the most adaptable food growers?

Chapter 16: Where are the most adaptable food growers?

Little: The Pacific Northwest has taken innovative approaches to climate and food production. There’s an intersection of old-world solutions combined with technology. There’s a lot happening in Silicon Valley. And a lot of those creative solutions in the private sector are happening all over the world — Israel, India, China, California, and the Bay Area. That is a source of optimism for me.

The ballgame in terms of major change is going to be in Washington, D.C., in the next four years. I’m really hopeful that there are incentives, that there’s a path forward in policy, clear practices that can be put in place on mid- and small- and large-scale farms that can encourage a precipitous shift toward conservation agriculture.

It’s a political challenge. Will it look like a cap-and-trade program, where farmers buy and sell carbon credits? Will it just be incentive and tax credit programs for practices that they’re beginning to input? We don’t have a standardized way of measuring carbon content in soil. That needs to happen. So where is the exciting progress happening? In the private sector and academia. But the real action and my hope is that the most significant change will be made in Washington.

Chapter 16: How has the pandemic changed people’s perceptions about food?

Little: The pandemic exposed and accelerated a lot of existing problems in food supply chains. We began to see how antiquated our food systems are. It’s all the more problematic as we face increasing climate pressures. The pandemic will serve as a preparation for more severe disruptions of food production and distribution. We have an opportunity to prepare for what’s ahead. It will take consumer awareness and political will to solve the problems.

Chapter 16: In what ways has your research changed the way you personally live and eat?

Little: I have cut out red meat, not because of my own moral rigor, but because I have a 12-year-old daughter who has held me accountable. She has been a source of moral courage, as have my students who are in the 18- to 21-year-old range. If not for them, I would still be eating the steak my husband made for my son last night.

We’re a divided household. They are not absolutists. My daughter is and she has basically said, “You’ve got to walk the walk, Mom.” We don’t eat red meat. We are adopting more of the meat alternative products — Beyond Meat burger and other Beyond Meat products. Gardein chicken strips are pretty convincing. We have not become fully vegan or vegetarian. I’m an unsuccessful vegetarian. We’re doing what we can to eliminate red meat and other meat products. That’s been a struggle, so I commiserate with all readers who struggle with that.

Food waste is the other issue or topic of conversation in our household — we save leftover coffee in the pot to use for cold coffee the next day. Composting is not necessarily the best answer in preventing food waste. Composting makes us feel better, but the real carbon impact is in the growing of the food and transporting of those high-carbon foods from Yuma, Arizona, or Salinas, California, where 90-plus percent of lettuce is produced.

If you’re growing in your backyard, then of course composting is a great solution. I have a lifestyle that has not prioritized producing my own food or getting the majority from local sources. As I’ve admitted, I do most of my shopping at Kroger.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Peggy Burch is now the arts and culture editor at The Daily Memphian and a member of the Humanities Tennessee Board of Directors. She holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.