Getting it Right

In the first of a two-part interview, veteran journalists John Egerton and John Seigenthaler talk about books, newspapers, and the single most important historical event of the twentieth century

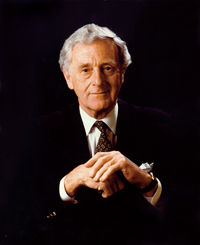

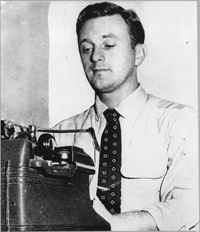

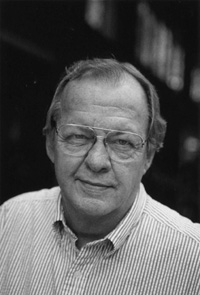

On October 15, veteran Nashville journalists John Egerton and John Seigenthaler sat down for a conversation in Seigenthaler’s office in the First Amendment Center on the campus of Vanderbilt University. Egerton, seventy-seven, a veteran freelancer and the author of many acclaimed books, came to Nashville in 1965 as a magazine staff writer and has been based there ever since. Seigenthaler, eighty-five, was born in Nashville, went to work as a reporter for The Tennessean in 1949, and retired forty-two years later as the paper’s editor and publisher. Egerton has called Seigenthaler “the foremost journalist in Tennessee history.” In addition to his contributions at The Tennessean, Siegenthaler also served as the first editorial director of USA Today, as chairman of both the John F. Kennedy “Profiles in Courage” Awards and the Robert F. Kennedy National Book Awards, and as founder of the First Amendment Center, which now bears his name. For more than forty years, he has hosted Nashville Public Television’s A Word on Words, a weekly interview program featuring prominent novelists, journalists, and historians from around the country.

Chapter 16 will publish an abridged version of the Egerton-Seigenthaler conversation in two segments. The first, which appears below, focuses on books, newspapers, and the printed word. The second, which will appear on Monday, concerns an unvetted Wikipedia entry on Seigenthaler that falsely implicated him in the murders of both John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy.

Chapter 16 will publish an abridged version of the Egerton-Seigenthaler conversation in two segments. The first, which appears below, focuses on books, newspapers, and the printed word. The second, which will appear on Monday, concerns an unvetted Wikipedia entry on Seigenthaler that falsely implicated him in the murders of both John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy.

John Egerton: All through your youth, even when you were a big kid, your mom and dad both read to the children, starting with you, the eldest, and expanding to a total of eight.

John Seigenthaler: Absolutely. It was a nightly habit, and they each read, I guess, from their own background of interest. I remember my mother started with the Junior Classics and graduated to Shakespeare. She was reading Shakespeare to me by the time I was seven or eight years old. And there are speeches from Shakespeare I can recite right now:

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it

To you, trippingly on the tongue. But if you mouth it,

As many of your players do, I had as lief the town-crier

Spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with

Your hand, thus….

Egerton: What’s that from?

Seigenthaler: It’s from Hamlet. And the last time Jack was here—my grandson, who’s interested in theater—I read [Henry V]:

O, for a muse of fire that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention!

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leash’d in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment.

Egerton: My God, that is impressive.

Egerton: My God, that is impressive.

Seigenthaler: Not impressive, just—it’s my mother. And my father read Tom Swift, the Rover Boys. He read basically boy-adventure stories, and she focused on Charles and Mary Lamb first and then went directly to Shakespeare and the poets. I memorized. And, you know, it made school so much easier. And then if you listen to all that reading, when the time comes to write, you’ve got something. You understand what a simple declarative sentence is—and we both know that’s maybe the toughest thing to write.

Egerton: It is. OK, so then you go to Father Ryan High School, and you have an encounter with Father Goett.

Seigenthaler: Theophane Goett.

Egerton: And he gave you a book.

Seigenthaler: He was a Franciscan priest and he was teaching me math. And one day I’m headed down the corridor, and he shouts my name. And, you know, I’m one of eighteen, twenty kids in his math class, and by no means at the top of the class. What I assume is that faculty—mostly priests, a couple of nuns—talked among themselves about students and had an understanding about kids and where their interests were, and for some reason he calls my name out and gives me The Mind of the South.

Egerton: W. J. Cash.

Seigenthaler: Jack Cash’s book, yeah. Cash had committed suicide by then, and I had no idea who Jack Cash was until I started reading it.

Egerton: This would have been up in the ’40s when the war was going on.

Seigenthaler: Yes, it would have been about ’43. And it just rang my bell. It made such a difference to me. I suddenly realized that Cash was talking about a lot of us—himself, the whole culture. I read it and took it back to [Father Goett], and gave it to him in math class. And he said, “Did you get anything out of it?” And I don’t remember what I said, but we talked about it. And what is puzzling is why this man in a long brown robe, with a white rope around his waist and sandals on his feet, among maybe 150 kids he teaches during the course of a week, singles me out to read that book. And, you know, it made an impact.

Egerton: Yeah. Cash had written an article called “The Mind of the South” in Harper’s or The Atlantic or someplace. And Alfred Knopf, the publisher—still today the best publishing house in America—saw that article and sought out Jack Cash in Raleigh-Durham, and flew down there and went to lunch with him. Cash was a newspaper guy. And there’s a famous picture of the two of them sitting at a lunch table.

Seigenthaler: Really.

Egerton: And Alfred Knopf pleaded with him to make a book out of it and patiently waited. This was like in ’36. And waited through four years for him to finish the manuscript, because he saw from that one article that this was a vision of what the South is, and what was about to happen to it, that nobody else seemed to have around that time. And, in fact, you could fairly well say that nobody who was writing about the South at that time was saying those things. It was not a polemical book—not a call to action for liberal white and blacks.

Seigenthaler: No, it was not.

Egerton: It wasn’t that kind of book at all. It was a very erudite and thoughtful and penetrating book. The book came out, and Cash was terrified of what the reaction would be. Partly fearful, I guess, of what would happen around him, in the South, but also he was a quiet guy who didn’t like the limelight. The book was generally well-received. It got good reviews in the New York papers. And he was invited to give the commencement address at the University of Texas that fall.

Egerton: It wasn’t that kind of book at all. It was a very erudite and thoughtful and penetrating book. The book came out, and Cash was terrified of what the reaction would be. Partly fearful, I guess, of what would happen around him, in the South, but also he was a quiet guy who didn’t like the limelight. The book was generally well-received. It got good reviews in the New York papers. And he was invited to give the commencement address at the University of Texas that fall.

Seigenthaler: Was he really?

Egerton: December of ’41. And took his wife and was on his way to Mexico on a vacation—but he hanged himself with his own necktie in his hotel room in Mexico City soon thereafter, like in early January.

Seigenthaler: I didn’t know why he was in Mexico when he died….

Egerton: Well, I want to come back to Cash and books and the South of that era later on, but first, you went in the Air Force for three years, and in 1949 you came back to Nashville, and your uncle helped you get a job at The Tennessean.

Seigenthaler: At The Tennessean, yes.

Egerton: Did you have any ambition at that time to be a newspaper reporter?

Seigenthaler: I had written in high school. I had written for the paper. I had ambitions. I really, though, wanted to be a schoolteacher. I absolutely wanted to be a schoolteacher, and my mother knew that, and I guess it was reading that maybe hooked me on that. And I had continued to read heavily while I was in the Air Force. I read a lot, and I did write for the base newspaper.

When I got out, my uncle, who worked for the newspaper, brought me in to meet Coley [Coleman] Harwell, and Coley asked me if I would bring him some references. One I used was George Rowling, who had taught me English at Father Ryan, and who had befriended me, and who [kept] me, in 1945, from dropping out of school and going into the military. I remember he took me over to what was called the Priests’ Residence, next door, and really talked hard to my head, and said, “Don’t do that. Stick around.” And I did come back and graduated. Then I was about to get drafted, and so I joined the Air Force. Got out in ’49 and went to the paper that spring.

Almost as soon as I got there, I sat down with Coleman Harwell and Joe Hatcher, [later to be] the political writer, who was the managing editor in those days. And they had asked me to write something, and I can’t remember what I wrote, but I remember Hatcher said, “Look, you can write. All you have to remember is, just get it right.” And so I got it right as often as I could.

Egerton: By the next year, by 1950, what was to become the most consequential social event in our lifetimes was beginning to work its way through the courts. The Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court in 1954 was preceded by a whole raft of stories that came up through the courts in ’50, ’51, ’52. And the Supreme Court selected five of those cases in a very political fashion, actually.

Seigenthaler: Sure. That’s right.

Egerton: I think Chief Justice Warren did that because he knew how important the case was, and he wanted a clear decision on it, maybe even a unanimous decision. Anyway, you had been at The Tennessean for five years by then, by 1954. In thinking back on this, you say that you didn’t see that coming. Nobody white saw it coming, unless they were in the legal profession or in politics and saw it was going to be something they had to deal with.

Seigenthaler: Right.

Egerton: But everybody was in denial, and here came Brown, and you’re living in Nashville, working at the newspaper. All white guys, no women except Nellie Kenyon [a veteran court reporter]. No blacks. Segregation was everywhere. The churches were that way, business was that way. And here comes this story. And the first thing you knew about it was when the Catholic bishop in Nashville desegregated the Catholic schools that fall.

Seigenthaler: That’s right.

Egerton: What do you remember about that?

Seigenthaler: Well, I remember he was an interesting guy. Bishop Adrian. William L. Adrian, he’s the guy who did it. If you read his writings—and he wrote extensively after he retired—he was a religious conservative, but he also understood that Brown v. Board of Education or not, the time had come to do something about segregation in the schools.

Egerton: And they did, and did it right then.

Egerton: And they did, and did it right then.

Seigenthaler: That’s right, did it ahead of everybody else.

Egerton: Ahead of the public schools and all the rest. In that whole decade of the ’50s, a lot happened [on the desegregation issue]. Nashville happened, Little Rock happened. The Truman-Eisenhower years. You went for a Neiman [Fellowship at Harvard] in 1958-59, I believe. And you had all these guys you worked with down at the paper: Gene Graham, Fred Graham, Nat Caldwell, Dick Harwood, David Halberstam and Wallace Westfeldt and Tom Wicker, all those people, working for Coleman Harwell.

Seigenthaler: Working for Coleman Harwell. He hired them all.

Egerton: And somehow, either by accident or by his design, he had picked a bunch of Southern white guys—or out-of-South white guys like Halberstam—who were basically liberal Democrats.

Seigenthaler: Right.

Egerton: How did he do that?

Seigenthaler: You know, I don’t know. Westfeldt was first—he was older; he and Coley had both gone to Sewanee. A couple of years ago, maybe just last year, Westfeldt sent me a copy of a memo from 1953. Coley has written to him and says, “Brown v. Board of Education [is coming].” I don’t know that he called it that, but he says something about these cases are coming, and we need to look ahead [and think about how to cover this at the paper]. What I have is the copy of the memo Westfeldt sends back to Coley. And he says, “I think we should create a team now that begins to look not just at education, but at race generally in the South.” And the result of that was that there was an informal group talking about race during that time.

Westfeldt moved among all of us pretty well. First of all, he was charming, and he was smart. And he had been off on a fellowship the year before he wrote this memo, and he puts together this group, and we don’t meet very often, but when we meet, he’s making sure that we are reading everything that we should be reading. He is also the correspondent for the Southern Education Reporting Service [which reported on desegregation].

Harwell saw this as a way to get us together and to get our heads on straight about where the paper ought to be and where we were going to go. Harwell was creating in that newsroom a culture, a core of young reporters—Wicker, Halberstam, me; Richard Harwood came later. Westfeldt didn’t like Harwood much, but he put him on the list because he knew he was good. And it was just occasional sitting down with Coley and talking about where things are going and how things are going. And all of us were assigned to go to [Fisk sociologist] Herman Long’s Race Relations Law Institute. At least one summer, maybe two, we all went out there and sat in on conferences and then talked among ourselves about it.

But the exchange of original memos between Coley and Wally comes before Brown comes, and is anticipatory. He says, “It’s coming and I’d like for this staff to be prepared.” And you’d think one way you’d prepare for that would be, “Let’s look at the school system.” He didn’t go there at all. What he was really trying to do was make sure there were people on that staff who had their heads on straight and who were going to report the news the way the news broke.

Egerton: Around the time of the Brown decision, Carlton Loser—the Tennessee district attorney general for Davidson County for almost twenty years before he was elected to Congress in 1956—gave you a book called South of Freedom.

Seigenthaler: Yeah, by Carl Rowan.

Egerton: Carl Rowan, who was born and raised down near McMinnville, in a family that traced back to slavery. His grandparents or great-grandparents had been slaves. Carl Rowan went to the Minneapolis Tribune and became a great reporter and then wrote South of Freedom about trips that he made down into the South, and the book came out in ’52. So here’s another W. J. Cash red flag being waved at the South….

Seigenthaler: Absolutely.

Egerton: At everybody in the South who thought they could defend segregation forever, as George Wallace said. There were now these other people saying, “Think again, you’re not going to be able to.” And Carlton Loser, when he was the D.A. here, gave you that book. Well, why did he give you that book? Was this another Father Goett moment?

Seigenthaler: It is exactly the same circumstance. I have no idea.

[To read the second part of this conversation, please click here.]

On October 30 at 7 p.m., John Seigenthaler will speak on “First Amendment Challenges Posed by New Media Technology” at the Massey Performing Arts Center on Belmont University campus in Nashville. The event is free and open to the public. Click here for ticket details. On November 8 at 11:30 a.m., Seigenthaler will receive the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee’s 2012 Joe Kraft Humanitarian Award. Tickets to that event are $75. Click here for details.