“You Are Where You Come From”

Poet, translator, and editor Don Share talks with Chapter 16 about his new book, the centennial year of Poetry magazine, and his Memphis roots

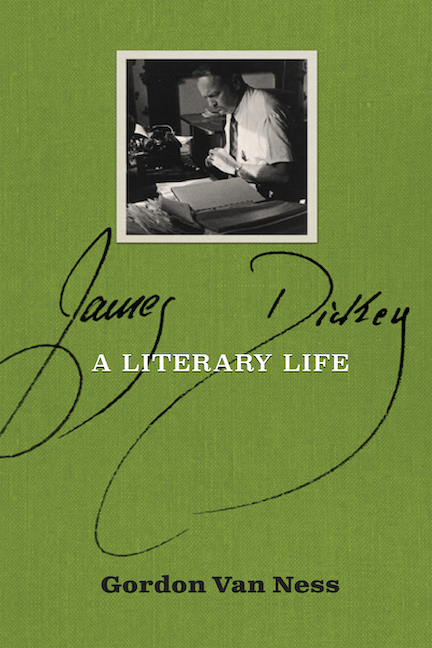

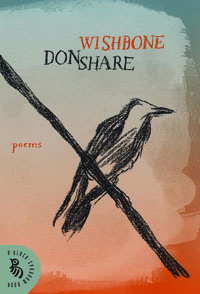

Memphis native Don Share, poet and senior editor of Poetry magazine, has recently released his third poetry collection. In Wishbone, Share energizes his well-crafted lines with wit and hard-wrestled emotional truths. Many of the poems in Wishbone reflect on the transient nature of life and our attempts to muddle our way through loss. As Share explains in an interview with Chapter 16, “We’re always using whatever strength we have to grasp things, to hold on, and sometimes to wave goodbye.”

In addition to his poetry collections, Share is the author of numerous works of criticism and translation, including Bunting’s Persia (Flood Editions, 2012), Seneca in English (Penguin Classics, 1998), and Miguel Hernández’s I Have Lots of Heart (Bloodaxe Books, 1997), which received multiple awards including The Times Literary Supplement Translation Prize. Known for his craftsmanship, Share excels in all manner of forms and styles, in poems as short as haiku and as wide-reaching as Whitman. From Agincourt to food courts, bee hives to highways, holy to the unhinged, these poems surprise, redrawing their boundaries at every turn of the page.

Share recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: One of the many quiet yet tense poems in this collection is “On Smoking out Some Bees with a Flaming Torch.” “The hand” that reaches into the nest might be the death that reaches for all of us. In fact, many of the poems in Wishbone consider ends and after-lives. Would you call this a thematic unity to the collection?

Chapter 16: One of the many quiet yet tense poems in this collection is “On Smoking out Some Bees with a Flaming Torch.” “The hand” that reaches into the nest might be the death that reaches for all of us. In fact, many of the poems in Wishbone consider ends and after-lives. Would you call this a thematic unity to the collection?

Don Share: While I was working on the poems in the book, a number of people I was very close to became ill or died, and I became ill myself—so yes, that got into it. The hand of death has an extensive reach, no doubt about it; yet the hand that reaches into the nest is also the ingenious hand of human life, willing to risk being stung, always trying to grasp whatever’s out there. We’re defined by our reaching for things, our reaching out to people, and we do it as long as we can. When my father was dying, there were times in which gesturing with one hand was the only way he could communicate with the world. It was vivid, and even shocking, to realize how much power there is in a hand, in the fingers. We’re always using whatever strength we have to grasp things, to hold on, and sometimes to wave goodbye.

Chapter 16: The title poem, “Wishbone,” begins with a clear, assertive voice: “I have a bone to pick / with whoever runs this joint.” The “joint” is our world, and the god here comes across as an inept manager who has some communication problems with his staff. Many poets find it quite difficult to approach religion in poems. What are some of your strategies for doing so?

Share: Yes, the joint is the whole big world: there are times when we ask, “Hey, who’s running all this?” “Looking Over My Shoulder” talks similarly about the “man upstairs.” It’s not that God is inept, but it’s more about that feeling we have sometimes: “Who do we complain to?” I’m playing around with that desperation—and whininess. As it happens, “Wishbone” is in the voice of a dying cat, and from his perspective, human beings are in charge, making godlike decisions in the face of which he feels powerless, though this is a tough cat and he suffers no loss of nobility or character even at the very end of it all. Needless to say, a cat can’t talk; I wanted to give one language for a short spell so he could speak his piece. A bit of tragicomic relief, you might say.

Chapter 16: In your blog, you quote Jeanette Winterson, who recently rebuked the notion that poetry is a luxury, something to do when one has leisure time: “A tough life needs tough language—and that is what poetry is,” she wrote. “That is what literature offers—a language powerful enough to say how it is. It isn’t a hiding place. It is a finding place.” Can you talk a bit about how your own poems in Wishbone serve as a finding place?

Share: That quote is in Winterson’s latest book, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? and it means a lot to me. A writer’s job is to say how it is. Well, I suddenly find myself at the age when real loss sets in. I was used to being so young! So I’m finding out what we all find out, if we stick around long enough. But it’s not easy, and we certainly don’t have much choice. The poems in Wishbone describe what it’s like to have obstacles thrown in your way, but there really is something both funny and sad about it. That’s what we find out, if we stick around long enough: what can be said.

Chapter 16: Critics have commented on the haiku-like nature of your poems—they’re not only compressed, but many are quite short. “Fortune,” for example, consists of four lines: “Gunmen come / from homes / with nice / china.” How would you explain this poem if you were teaching it?

Chapter 16: Critics have commented on the haiku-like nature of your poems—they’re not only compressed, but many are quite short. “Fortune,” for example, consists of four lines: “Gunmen come / from homes / with nice / china.” How would you explain this poem if you were teaching it?

Share: I’m not sure I would teach that poem! The idea is that we come into the world with innocence, in warmth, and then… something happens. You know that moment when they talk to the family or neighbors of someone who’s done something terrible, and they just can’t believe it? It’s that feeling of shock that I was thinking about. But also the danger: there’s no telling when someone is going to lose his innocence, or what will happen next. If you had a good home, you definitely leave it behind when you do something you weren’t raised to do.

Chapter 16: Much of your work, both as an editor and as a writer, promotes this art. Does Poetry have anything new in the works to help poetry reach a larger audience?

Don Share: It’s the magazine’s centennial year, so we’ve been doing quite a lot. We recently gave away some 60,000 copies of the magazine to 10,000 book groups, to let people see what contemporary poetry is up to. Our website has thousands of poems and articles about poetry for people to read, and we have podcasts in which we talk about poets and their work. Our programs include Poetry Out Loud, which gets high school students to memorize poetry; an online learning lab for students and teachers; a children’s poetry program, featuring the nation’s Children’s Poet Laureate; and many others that reach out to people everywhere who already love or who would like to know more about poetry.

Chapter 16: Are there any ways in which you see yourself as a specifically Southern writer? Any ways growing up in Memphis particularly has affected your poems or the way you think about the nature of your writing?

Don Share: I do see myself as a Southern writer. My first book, Union, was very explicitly about Memphis and about the South in general. I don’t live there now, but its whole way of life has warmly permeated everything I think and do; it never leaves me. The music, the food, the weather, the way people talk—these things are not clichés; they nourished me every step of the way. You are where you come from.