Getting to Know A. Lincoln

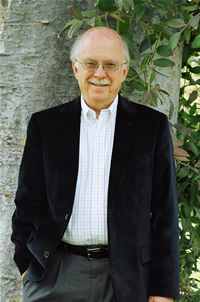

Ronald C. White Jr. talks about the moral growth and modern relevance of the sixteenth president

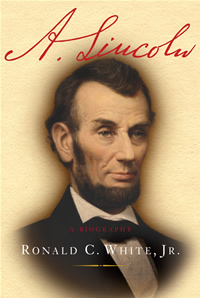

In writing The New York Times bestseller A. Lincoln, Ronald C. White Jr. did much more than produce another in a long line of Lincoln biographies. He also delivered a detailed yet accessible and, perhaps most importantly, personal history of a man many Americans think they know, but with whom most have only a passing familiarity. Often praised as a paragon of virtue, sometimes reviled as a blood-stained dictator, Lincoln has remained aloof from all but the most dedicated students. He is a man more marble than flesh, an ever-present image without a human heart. White argues that Lincoln can, and should be known as a person, and that this knowledge should be gained anew by every generation of Americans.

White, a professor of theology, wrote two books about Lincoln’s speeches and writings before tackling the task of a full biography. His focus on Lincoln’s evolving use of words allowed him to trace the president’s development not just as a politician and commander-in-chief, but as a person who struggled daily with that most daunting of human endeavors—defining himself. Notes that Lincoln left behind, says White, “reveal a man of intellectual curiosity who was testing a wide range of ideas, puzzling out problems, constructing philosophical syllogisms, and sometimes disclosing his personal feelings.” This journey of self-discovery is what makes A. Lincoln such compelling reading. White recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email about his Lincoln research.

Chapter 16: A. Lincoln is your third book about the sixteenth president. What drew you to him as a subject and kept you interested?

Ronald C. White: In 1993-94 the Huntington Library put on a huge exhibition on Lincoln. I attended the Scholar’s Conference, but knew nothing about Lincoln or any of the scholars. Teaching in the History Department at U.C.L.A., I had the option to offer a seminar of my choice each year. Why not offer a seminar on Lincoln? Always seeking ways to get students involved, I decided to bring students to the exhibit, and find someone at the Huntington—not me—to give them a lecture on Lincoln.As we read an anthology of Lincoln’s speeches and letters, I found myself drawn to Lincoln and his words—especially his Second Inaugural Address. That was the beginning.

I continued to write about him because he is endlessly fascinating. We will never get to the end of his moral greatness. I believe that each generation brings its own questions to Mr. Lincoln. Standing on the shoulders of previous Lincoln biographers, I believed there was much more that contemporary Americans needed to know.

I continued to write about him because he is endlessly fascinating. We will never get to the end of his moral greatness. I believe that each generation brings its own questions to Mr. Lincoln. Standing on the shoulders of previous Lincoln biographers, I believed there was much more that contemporary Americans needed to know.

Chapter 16: By common estimate, Lincoln is the subject of about 16,000 books. Was it difficult for you to find a fresh angle on such a heavily analyzed man?

White: First, there are always new Lincoln discoveries. I was able to take advantage of the remarkable discovery of Lincoln legal papers, some of them found only in the last twenty years.

Second, I continue to believe that Lincoln’s link to modern Americans is his words, but in traditional biographies the only speech that received much ink was the Gettysburg Address. There is so much more to say.

Third, many people have commented that I have written such a “personal” book about Lincoln. I am interested, and I have discovered readers are interested, in the inner Lincoln, his thoughts and struggles. We also want to know about Lincoln the son, husband, father, and friend.

Chapter 16: Your academic background is in theology, and you have written about the influence of religion on American society. Did your study of religion affect your view of Lincoln in any way?

White: I found myself surprised at how Lincoln biographers and historians moved so quickly over Lincoln’s faith journey. In casting about for a next biography after Lincoln, I found the same tendency, be it Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, or Jimmy Carter. Some say [Lincoln] used religious language, but there is so much more to analyze. How did his religious beliefs change over time? Who were the chief influences upon him? I argue, for example, that Phineas Densmore Gurley, the minister of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, is the missing person in the Lincoln story. Gurley preached the funeral sermon for Willie Lincoln in February 1862. A remarkable sermon—Lincoln asked for a copy, which he carried with him. I believe one cannot understand Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address without understanding the influence of Gurley and the Old School Presbyterian theology of providence. My education in and teaching of American religious history has sensitized me to the use of religious language.

Chapter 16: You describe Lincoln as a man “always comfortable with ambiguity.” How do you think he would fare as a politician in today’s winner-take-all, hyper-partisan climate?

White: In our polarized political climate we have little regard for politicians who are comfortable with ambiguity. Whether on the right or the left, too often we want politicians to speak to us in absolutes—I will never raise taxes no matter what the context or circumstances. Lincoln combined high ideals with pragmatic decision making. As a lawyer he learned to put himself in the shoes of his opponent. He believed he could not articulate his own position if he did not at the same time understand, with empathy, the position of his opponent. We have lost this perspective today and we are the poorer for it. I do not simply blame the politicians; the blame is really [with] us, the public, who seem unwilling to grapple with the complex—yes, ambiguous—issues we face today.

White: In our polarized political climate we have little regard for politicians who are comfortable with ambiguity. Whether on the right or the left, too often we want politicians to speak to us in absolutes—I will never raise taxes no matter what the context or circumstances. Lincoln combined high ideals with pragmatic decision making. As a lawyer he learned to put himself in the shoes of his opponent. He believed he could not articulate his own position if he did not at the same time understand, with empathy, the position of his opponent. We have lost this perspective today and we are the poorer for it. I do not simply blame the politicians; the blame is really [with] us, the public, who seem unwilling to grapple with the complex—yes, ambiguous—issues we face today.

Chapter 16: By most standards, Lincoln was a very private person. He left no journal, he rarely commented publicly about his private life, and of course he was never able to write a memoir. How can a biographer get close to such a reticent subject?

White: My newest lecture suggests he did keep a diary. In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln are what the editors call “fragments.” These are little slips on which Lincoln worked out his thinking. They are all untitled and undated and unsigned, but they deal with the most important questions of the day: slavery, government, where is God in the midst of the Civil War. In one, Lincoln compares himself to Senator Stephen Douglas, and writes, “My life is nothing but a failure—a flat failure.” This is the private Lincoln; certainly he would never have said this in public.

Chapter 16: Were you surprised by anything you learned about Lincoln?

White: I was most surprised by his faith journey. In the Second Inaugural Address, delivered on March 4, 1865, forty-one days before his death, Lincoln mentions God fourteen times, quotes the Bible four times, and invokes prayer three times. Yet, this remarkable address has not elicited any of the attention it deserves. My quest was to discover where this language came from.

Lincoln was raised in a Baptist home in Kentucky and Indiana. He reacted against the emotionalism of this tradition of Christianity, believed it did not allow him to ask the questions bubbling up in his young mind. He rejected it and became a skeptic. He called himself a “fatalist”—if there is a God it is the God of Jefferson, a watchmaker who sets the universe in motion but does not enter into history.

But then, like many of us, when tragedy occurs in midlife—not only the deaths of 620,000 in the Civil War, but the death of his son Willie at age eleven—Lincoln is forced to reconsider the faith he abandoned. He cannot readopt his parent’s faith, but must find one more congenial to his rational temperament. Lincoln’s long private struggle with faith becomes public on March 4, 1865. In response to a letter of congratulation from a Republican politician, Lincoln called the Second Inaugural “my best effort.”

On September 26 at 5:30 p.m. in Pfeffer Hall on the campus of Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville. Ronald C. White Jr. will give a lecture titled “The Meaning of the Civil War for Today.” The event is free and open to the public.