Giving Recognizable Shape to the Chaos of our Lives

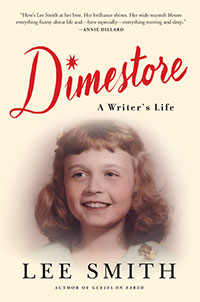

Novelist Lee Smith’s new memoir is a must-read for aspiring writers—and everyone else

Memoir is not the exclusive stomping grounds of writers at or beyond mid-life, of course; true stories—deserving of capture and beautifully crafted—have emerged from very young minds. But there is something especially valuable, something especially rich in wisdom, about a memoir that reveals a long life well lived. A memoir in which a gifted writer looks back, all the way back, and then takes us through the years with her. This is what Lee Smith does in her new book, Dimestore: A Writer’s Life, and readers, whether versed in Smith’s backlist or new to her voice, are lucky to come along with her.

With thirteen novels and four collections of short fiction to her name, Lee Smith is virtually synonymous with Appalachian fiction. Born and raised in Virginia, she has long made her home in North Carolina. Her books have deeply mined the cultures and communities of the South, and this memoir begins with a loving remembrance of the mountain hamlet of Grundy, Virginia, where her father owned and ran the local five-and-dime.

With thirteen novels and four collections of short fiction to her name, Lee Smith is virtually synonymous with Appalachian fiction. Born and raised in Virginia, she has long made her home in North Carolina. Her books have deeply mined the cultures and communities of the South, and this memoir begins with a loving remembrance of the mountain hamlet of Grundy, Virginia, where her father owned and ran the local five-and-dime.

That “dimestore” proved rich terrain for a budding tale-spinner: “As a little girl,” she writes, “my job was ‘taking care of the dolls.’ Not only did I comb their hair and fluff up their frocks, but I also made up long, complicated life stories for them, things that had happened to them before they came to the dimestore, things that would happen to them after they left my care.” Smith also writes of spending hours “observing the whole floor of the dimestore through the one-way glass window and reveling in my own power—nobody can see me, but I can see everybody! I witnessed not only shoplifting, but fights and embraces as well. Thus I learned the position of the omniscient narrator, who sees and records everything, yet is never visible. It was the perfect early education for a fiction writer.”

Children today would envy Smith’s childhood: free, wild, conspicuously lacking in parental oversight. She and her friends “formed dozens of clubs, each with its secret handshake and code words,” and “ran our mountains ridge to ridge—climbing trees and cliffs, playing in caves, swinging on grapevines, catching salamanders, damming up creeks, building lean-tos and lookouts, playing Indians and settlers with our handmade slingshots or the occasional Christmas bow-and-arrow set.”

But she doesn’t whitewash her formative years; no self-respecting memoirist would even want to. She openly explores the bouts of depression that struck her parents, both of whom were hospitalized on occasion. Their absences left Smith poised to find her balance in the pages of books and in the generous hands of family friends. (Her mother and father were beloved among their peers.) While she is frank about the family’s struggles, her account suggests an upbringing that gave her just what a writer in training needed: abundant love alongside witness to pain, ample solitude alongside community. “This is my story, then, but it is not a sob story,” she writes.

In subsequent chapters, Smith reveals powerful pivot points in her education, both as a student and, later, as a teacher of writing. She pays homage to the many people who have profoundly affected her life and work: her professor Louis D. Rubin Jr., and Appalachian writers James Still and Lou Crabtree, whom Smith first encountered when Crabtree signed up for a class Smith was teaching at a festival in Abingdon, Virginia. Smith confesses a snap judgment: “Here was every creative writing teacher’s nightmare: the nutty old lady who will invariably write sentimental drivel and monopolize the class as well.” But she ends up delighted to be proven utterly wrong about Crabtree’s writing and spirit. “On Lou’s Porch” is a feel-good essay nonpareil.

Smith is equally forthcoming about her own early stubbornness regarding subject matter, something fellow writers may find familiar. When several college professors suggested she write about the world she knew, and not made-up worlds that didn’t ring true, Smith deemed it “terrible advice. I didn’t know what they meant. I didn’t know what I knew. All I knew was that I was not going to write anything about Grundy, Virginia, ever, that was for sure.” Lucky for us, of course, she changed her tune in the wake of a life-changing reading by Eudora Welty, who wakened her to what it really means to write from one’s own lived place, and whose words on the power of writing provide a fitting epigraph for Dimestore.

Smith is equally forthcoming about her own early stubbornness regarding subject matter, something fellow writers may find familiar. When several college professors suggested she write about the world she knew, and not made-up worlds that didn’t ring true, Smith deemed it “terrible advice. I didn’t know what they meant. I didn’t know what I knew. All I knew was that I was not going to write anything about Grundy, Virginia, ever, that was for sure.” Lucky for us, of course, she changed her tune in the wake of a life-changing reading by Eudora Welty, who wakened her to what it really means to write from one’s own lived place, and whose words on the power of writing provide a fitting epigraph for Dimestore.

This memoir is, in sum, less a detailed account of a beloved author’s trials and triumphs on the page than a meditation on what has mattered most in her life—subjects that have influenced her bestselling fiction in some form. Dimestore is a writer’s life in that it examines life in all its joys and sorrows and breathtaking flux. In one essay, Smith opens up about the early death of her son, who suffered from schizophrenia; in another, “Driving Miss Daisy Crazy; Or, Losing the Mind of the South,” she explores the changing nature of the region through the story of opening a sushi restaurant in Carrboro, North Carolina, with her husband, the writer Hal Crowther.

In that piece she also considers the predicament of the Southern writer, remembering a student who grew up in a peripatetic military family and so despaired of having “no sense of place, no sense of the past.” Smith suggests that the student’s memories—of hanging out at the mall, chain-smoking, and drinking Cokes— are their own sort of blessing: “For a writer cannot pick her material any more than she can pick her parents; her material is given to her by circumstances of her birth, by how she first hears language. And if she happens to be Southern, these factors may already be trite, even before she sits down at her computer to begin.”

And then, in one of the final essays, there it is, the wellspring of eminently quotable reflections on the writing life that Smith’s fans have been anticipating throughout this charming memoir: “No matter what I may think I am writing about at any given time—majorettes in Alabama, or a gruesome, long-ago murder, or the history of country music—I have come to realize that it is all, finally, about me, often in some complicated way I won’t come to understand until years later,” Lee writes. And she closes that essay, “A Life in Books,” with a graceful argument for the enduring power of writing: “Whether we are writing fiction or nonfiction, journaling or writing for publication, writing itself is an inherently therapeutic activity. Simply to line up words one after another upon a page is to create some order where it did not exist, to give a recognizable shape to the chaos of our lives. Writing cannot bring our loved ones back, but it can sometimes fix them in our fleeting memories as they were in life, and it can always help us make it through the night.”

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch, a nonprofit literary center. She is the author of This Will Go Down On Your Permanent Record, a novel, and numerous journal and magazine articles.