God Is Change

Martha Park embraces uncertainty in World Without End

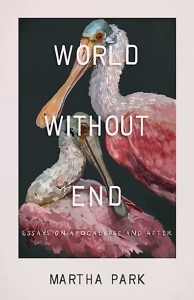

World Without End: Essays on Apocalypse and After is a deeply felt and carefully investigated collection about faith and science by writer, illustrator, and journalist Martha Park, who grew up in Memphis. Catalyzed in part by her progressive Methodist pastor father’s final year in the pulpit, Park explores opposing worldviews within the Christian church and the science community, using incisive research on biodiversity and belief systems alike to link these essays that weave the personal, the political, and the sacred.

“My father has transmitted something of his wiring to me,” Park writes in the first essay, “some leaning toward mystery, some ornery indecisiveness, some uncertain reaching toward faith.” This propensity for bewilderment is what propels the collection, which covers topics ranging from endangered species and Scopes Monkey Trial reenactments to Park’s own intimate experiences of parenthood.

In “The Ark at the End of the World,” Park and her husband visit a full-size replica of Noah’s Ark in Williamstown, Kentucky, outfitted with a petting zoo and three decks of interactive exhibits. The Ark Encounter was built by Answers in Genesis, the young-earth creationist organization that also owns the Creation Museum in nearby Petersburg. Before even stepping foot aboard the ark, Park observes how striking the location alone is — its geographical region being home to historic Cincinnatian fossils dating back more than 443.7 million years. “Depending on which roadside attraction you choose, you’ll be presented with opposing visions of the world and its origins: one in which the world is billions of years old and the product of constant, ongoing change; or one in which the world is more like 6,000 years old and in which all of earth’s life forms were created, fully formed, in only six days.”

This is a perfect microcosm for Park’s work in these essays: identifying the uncanny overlaps between conflicting beliefs and gently prodding at the heart of them. While Park wasn’t raised in the evangelical tradition and often sheds light on its dangers, she isn’t scornful but curious — taking care in her research and interviews, seeking to understand the rifts in the church and in the culture at large.

This is a perfect microcosm for Park’s work in these essays: identifying the uncanny overlaps between conflicting beliefs and gently prodding at the heart of them. While Park wasn’t raised in the evangelical tradition and often sheds light on its dangers, she isn’t scornful but curious — taking care in her research and interviews, seeking to understand the rifts in the church and in the culture at large.

As someone who grew up a pastor’s daughter in the evangelical church, I found Park’s writing to be empathetic and precise. One point she makes about Answers in Genesis’ insistence on certainty in the ark exhibits captures much of why I found myself walking away from that faith tradition: “Young-earth creationism promises you’ll never have to doubt,” she writes, “but in the end, certainty might be a barometer, not for the strength of one’s faith, but for its fragility.”

“Natural Ends” reads as part travelogue and part reportage from interviews Park conducts with practitioners of natural burials across Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Examining the wide scope of reasons that people choose to be buried in this manner, she also maps a metaphor of her own unmet need. While walking the grounds of Larkspur Conservation in Westmoreland, Tennessee, with her interviewee, Kellye, Park confides the loss of her father’s church and how she can’t imagine another faith community providing her with the same sense of fulfillment and belonging. “You’ve experienced a death,” Kellye replies. “But you don’t yet have a ritual for grieving it.” This resonated deeply with me, as it will with many readers who have chosen to seek meaning outside of inherited structures.

“The fears I had — of loss, and change, and time slipping through my fingers — seemed to be answered by the meadow Kellye and I walked through, where all around us bodies were disintegrating bit by bit, just as we are supposed to,” Park writes, “and when I think about the decay of the body — cells breaking down, the body’s nutrients returned to the soil by microbes and bacteria, to be consumed by insects and fungi and be integrated into the life cycle of the land — it seems clear that, no matter what happens to a person’s soul, the body lives on for who knows how long in the world around us: Heaven is just a breath away.” She discovers that natural burial is just one of many meaningful opportunities we have to embrace the holiness of change.

The idea of God as change is one Octavia Butler famously wrote about, and it’s foundational to many of the essays in World Without End. In a particularly beautiful lyric essay about the birth of her child and the slippage of narrative, Park writes: “As a kid, I prided myself on my spelling abilities, but two words consistently tripped me up, then and now: ‘alter’ and ‘altar.’ By virtue of my confusing them for each other, these words will probably always be interchangeable and bound up in each other in my mind: change, and a place for worship — or, if not quite worship, exactly, then a place where ‘we turn [ourselves] inside-out,’ inviting the sacred to move a little closer.”

While she no longer attends church, Park has learned that the innate wiring she has in common with her father, that charge toward mystery, continues to make new connections, new sites for the sacred. Her research of the natural world similarly points back to the patient faith of her upbringing, a faith that doesn’t hinge on apocalypse but “mirrors the uncertain world in which we live, the one that never really ends but keeps on changing.”

Lou Turner is a writer and musician based in Nashville. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry from Randolph College and is the author of Twin Lead Lines, forthcoming from Third Man Books in September 2025. She edits Quarter Notes, a lit mag with a musical ear.