Great Stories Live Here

Chapter 16 hits Chattanooga for the seventeenth biennial Celebration of Southern Literature

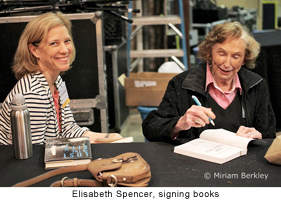

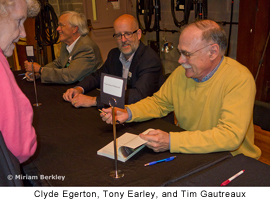

“Being Southern is something you just are,” novelist Elizabeth Spencer said at last month’s Celebration of Southern Literature, the biennial gathering of the Fellowship of Southern Writers: “I couldn’t turn it off if I tried. And I never tried.” Now ninety-one, Spencer is a charter author of the Fellowship and one of only two female members (the other was Eudora Welty) among the original group, which was founded in 1987. Sponsored by the Southern Lit Alliance (formerly the Arts & Education Council), this year’s gathering—the seventeenth— included participation by more than twenty-five members of the Fellowship, who handed out ten awards for fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and drama, including the Cleanth Brooks Medal for Lifetime Achievement to Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Beth Henley. The group also tapped two new members: Louisiana novelist Tim Gautreaux and Kentucky poet Maurice Manning, who remarked, “My heroes are in this room, and the spirits of prior heroes are here as well. It’s an honor to be in their company.”

This is a group of working heroes: Elizabeth Spencer’s first book, Fire in the Morning, was published in 1948; her next, a story collection called Starting Over, is due this winter from Norton.

Fittingly, then, the celebration began early on Thursday morning with a series of sessions called “Writers Discussing Their Craft” at the downtown branch of the Chattanooga Public Library. Jamie Quatro, whose debut collection of short stories, I Want To Show You More, had just been published, kicked off the conference with novelist Jill McCorkle by leading a small-group discussion of the short story. Concurrent sessions at the library were led by novelist Clyde Edgerton, poet Andrew Hudgins, novelist Bobbie Ann Mason, poet Ellen Bryant Voigt, and others. Quatro opened by saying that for her a story often begins with sound. As a young child she was lulled to sleep at night by her concert-pianist mother’s practice sessions. When the music stopped, Quatro would continue the performance in her imagination by changing the musical notes into words: “There’s a pulse, or a cadence, or a rhythm that you hear, and it translates into a sentence,” she said. McCorkle compared the introduction of characters in a story to the individual instruments in an orchestra, suggesting that “your goal is eventually to conduct a symphony.”

Fittingly, then, the celebration began early on Thursday morning with a series of sessions called “Writers Discussing Their Craft” at the downtown branch of the Chattanooga Public Library. Jamie Quatro, whose debut collection of short stories, I Want To Show You More, had just been published, kicked off the conference with novelist Jill McCorkle by leading a small-group discussion of the short story. Concurrent sessions at the library were led by novelist Clyde Edgerton, poet Andrew Hudgins, novelist Bobbie Ann Mason, poet Ellen Bryant Voigt, and others. Quatro opened by saying that for her a story often begins with sound. As a young child she was lulled to sleep at night by her concert-pianist mother’s practice sessions. When the music stopped, Quatro would continue the performance in her imagination by changing the musical notes into words: “There’s a pulse, or a cadence, or a rhythm that you hear, and it translates into a sentence,” she said. McCorkle compared the introduction of characters in a story to the individual instruments in an orchestra, suggesting that “your goal is eventually to conduct a symphony.”

Novelist Allan Gurganus continued the musical theme in his session with novelist Richard Bausch by saying that the writer is ultimately “trying to sing—not only writing prose that is sense-making but that is musical.” He advised writers in the audience to read their work aloud, listening for the dull sound of the “plastic glass” hidden among the clear-ringing tones of the crystal ones; then, he said, “you just start taking out those plastic glasses.” Bausch took the session beyond craft to discuss the spiritual and humanistic dimensions of what he called “a sacred art” that enables individual minds to meet across tremendous distances of time and space: “That’s what you are partaking in when you sit down to write,” he said. “You’re a part of that, not different in kind than anybody who ever tried to write. And to me that’s worth everything in life. Why not spend time trying to write?”

Gurganus continued in that numinous vein, sort of, by suggesting that “if God is a part of speech, God is a verb” and reflecting on the power of strong and interesting verbs in a sentence. McCorkle returned to the pragmatics of writing by describing a sign she keeps over her desk: “When the horse is dead, get off of it.” And Bausch stressed the importance of maintaining a daily writing practice free from self-criticism: “This day’s work,” he said. “At the end of the day, did I work? If the answer is yes, no other questions.” Quatro, the mother of four children, repeated McCorkle’s early advice to her that “you can write in the carpool line” if necessary. And all four speakers pointed out the difference between the free-flowing, organic, intuitive process that is necessary to create a first draft and the more disciplined, critical eye required to tackle subsequent revision, a process Bausch characterized as “where the real artistry is.”

Gurganus continued in that numinous vein, sort of, by suggesting that “if God is a part of speech, God is a verb” and reflecting on the power of strong and interesting verbs in a sentence. McCorkle returned to the pragmatics of writing by describing a sign she keeps over her desk: “When the horse is dead, get off of it.” And Bausch stressed the importance of maintaining a daily writing practice free from self-criticism: “This day’s work,” he said. “At the end of the day, did I work? If the answer is yes, no other questions.” Quatro, the mother of four children, repeated McCorkle’s early advice to her that “you can write in the carpool line” if necessary. And all four speakers pointed out the difference between the free-flowing, organic, intuitive process that is necessary to create a first draft and the more disciplined, critical eye required to tackle subsequent revision, a process Bausch characterized as “where the real artistry is.”

Following the small-group sessions, attendees gathered at the historic Tivoli Theatre, where the bulk of the conference was held, for greetings by Southern Lit Alliance President Jane Berz and Fellowship of Southern Writers Chancellor Allen Wier, awards presentations, readings by the new inductees, and panel discussions on a variety of topics. The first day ended with a rousing performance of excerpts from Good Ol’ Girls, a musical created by Lee Smith, Jill McCorkle, and musicians Marshall Chapman and Matraca Berg. Berg was unable to attend, but Clyde Edgerton stepped up with an impromptu rendition of his original composition, the comical “English Teacher Blues.”

A particular highlight the next day was the panel discussion of “Dramatic Scenes on Stage and in the Narrative,” featuring novelists Lee Smith and Elizabeth Cox, and playwrights Marsha Norman and Katori Hall. Smith began the hour: “What we’re trying to do as fiction writers,” she said, “is take our readers out of the chair they’re sitting in, out of the room they’re sitting in, out of the lives they lead, and put them into the world of our story.” To do this, she added, the writer must “create a sufficient world” through sensory detail: “It’s only through the body, weirdly, that we can get into the head.” Cox described a visit to the planetarium in Chapel Hill where she learned that the best way to see a comet was to look slightly away from it, and she suggested that fiction similarly “offers a peripheral vision that’s different from the regular way of looking at the world. Fiction tells you something by telling you to look somewhere else,” the indirect method being “the path that reaches the heart, in a way that direct observation and explanation can’t do.”

A particular highlight the next day was the panel discussion of “Dramatic Scenes on Stage and in the Narrative,” featuring novelists Lee Smith and Elizabeth Cox, and playwrights Marsha Norman and Katori Hall. Smith began the hour: “What we’re trying to do as fiction writers,” she said, “is take our readers out of the chair they’re sitting in, out of the room they’re sitting in, out of the lives they lead, and put them into the world of our story.” To do this, she added, the writer must “create a sufficient world” through sensory detail: “It’s only through the body, weirdly, that we can get into the head.” Cox described a visit to the planetarium in Chapel Hill where she learned that the best way to see a comet was to look slightly away from it, and she suggested that fiction similarly “offers a peripheral vision that’s different from the regular way of looking at the world. Fiction tells you something by telling you to look somewhere else,” the indirect method being “the path that reaches the heart, in a way that direct observation and explanation can’t do.”

Next, Norman discussed her struggle to “find the form that will carry the content of the story” and the techniques modern playwrights use to “release the boundaries between scenes,” allowing the action to flow more fluidly without breaks. She illustrated both points by reading an incredible scene from her new play, The War on Women, which was commissioned by the United Nations and deals with human trafficking and violence against women. Before Norman could begin to write the play, she explained, she had to figure out “how in the world to present this much information in two hours that people will sit through.” She solved the problem by setting the play in a television studio in which a documentary is being filmed. As the anchorman behind the news desk begins to interview an expert, he (along with the audience) sees the heart-breaking scenes she describes—such as of a father selling his daughter to a sex trafficker—being acted out in the shadowy corners of the studio, bringing the reality of the horror closer and closer until finally the young girl is placed into the reporter’s arms. Thus, a tragic yet impersonal situation happening to someone else far away suddenly becomes very personally his own problem as well.

Next, Norman discussed her struggle to “find the form that will carry the content of the story” and the techniques modern playwrights use to “release the boundaries between scenes,” allowing the action to flow more fluidly without breaks. She illustrated both points by reading an incredible scene from her new play, The War on Women, which was commissioned by the United Nations and deals with human trafficking and violence against women. Before Norman could begin to write the play, she explained, she had to figure out “how in the world to present this much information in two hours that people will sit through.” She solved the problem by setting the play in a television studio in which a documentary is being filmed. As the anchorman behind the news desk begins to interview an expert, he (along with the audience) sees the heart-breaking scenes she describes—such as of a father selling his daughter to a sex trafficker—being acted out in the shadowy corners of the studio, bringing the reality of the horror closer and closer until finally the young girl is placed into the reporter’s arms. Thus, a tragic yet impersonal situation happening to someone else far away suddenly becomes very personally his own problem as well.

Finally, Katori Hall—author of the widely performed play The Mountaintop—brought down the house with a virtuoso performance that no one present will soon forget. She first described her undergraduate writing teacher’s surprising advice: “You know you should be a playwright, right? ‘Cause all you write is dialogue!” Hall went on to express her envy of fiction writers; they have a narrative voice to fall back on, while the playwright must depend primarily on dialogue and stage directions to carry the exposition, action, and emotion of the story. For that reason, revealing the characters’ internal conflicts “can really pose a very interesting challenge.” She then read the opening scene from her new play, The Blood Quilt, in which four half-sisters meet on Sapelo Island in Georgia for a quilting bee and family reunion, gathering for the first time since their mother’s death. The play explores what it means to be a family in the face of conflict, loss, and even death—and it’s hilariously funny. The audience watched enthralled as Hall became each of her characters in turn, deftly conveying their anger, humor, pain, and fierce love for one another in a rapid-fire delivery that seemed to leave listeners stunned.

On the final day of the conference, hundreds in the theater watched another stunning performance as Elizabeth Spencer read “Rising Tide,” a short story that examines racism and bigotry as the protagonist, a recently divorced mother confronting life on her own for the first time, moves toward a greater acceptance of and even fondness for those with whom she initially fears she has little in common. In this passage, Marjorie watches as friends of her college-age daughter form a cheerleading pyramid in her living room during a party: “The red-headed girl lost balance. She swung from side to side. Marjorie held her breath again. Broken bones were worse than broken vases. Shrieks all around. The red hair tilting was a flaming torch. Arms rose up to her—brown, black, and white. Hands caught her by the ankles, and she steadied. Everyone clapped.” The image of the multicolored arms reaching up to steady the young girl at the top of the pyramid is a resonant one, not only for Marjorie, but for the Fellowship of Southern Writers, as it continues to celebrate the diversity of the South by including greater numbers of women and artists of color among its ranks.

On the final day of the conference, hundreds in the theater watched another stunning performance as Elizabeth Spencer read “Rising Tide,” a short story that examines racism and bigotry as the protagonist, a recently divorced mother confronting life on her own for the first time, moves toward a greater acceptance of and even fondness for those with whom she initially fears she has little in common. In this passage, Marjorie watches as friends of her college-age daughter form a cheerleading pyramid in her living room during a party: “The red-headed girl lost balance. She swung from side to side. Marjorie held her breath again. Broken bones were worse than broken vases. Shrieks all around. The red hair tilting was a flaming torch. Arms rose up to her—brown, black, and white. Hands caught her by the ankles, and she steadied. Everyone clapped.” The image of the multicolored arms reaching up to steady the young girl at the top of the pyramid is a resonant one, not only for Marjorie, but for the Fellowship of Southern Writers, as it continues to celebrate the diversity of the South by including greater numbers of women and artists of color among its ranks.

An early death prevented Flannery O’Connor’s election to the Fellowship but did not prevent from being the informally agreed-upon patron saint of this year’s conference. It was rare for her name not to be invoked as panelists discussed the craft of writing, what it means to be Southern, or the power of great literature. O’Connor’s spirit and her message of redemptive grace were most clearly in evidence during a panel discussion called “How Literature Saves Us,” when novelist Tony Earley expressed his ambivalence about the idea that literature offers salvation. “My mission as a writer is to suggest that we are worthy of saving,” he said.

He then read a powerful short piece, “Morning in America,” which describes a school shooting from the point of view of a victim—an emotionally charged subject at any time, but all the more disturbing four days after the Boston Marathon bombing. “When the bullet enters her heart, she leans back against a locker and watches Kyle fire the pistol again and again, his eyes closed now, his head turned away from the noise,” he read. “He looks afraid. As she slides slowly to the floor, she comes upon a revelation as if it were a vista, the whole world seen from a mountaintop, heaven and earth contained in an atom of thought. We just didn’t love Kyle enough, and he has suffered for it. She holds Kyle’s misshapen heart inside her chest as if it were the rarest gift. She wants to tell Kyle he is forgiven and ask him to forgive her. She raises her right hand above her head to get his attention and steps off into brightest sunlight.”

He then read a powerful short piece, “Morning in America,” which describes a school shooting from the point of view of a victim—an emotionally charged subject at any time, but all the more disturbing four days after the Boston Marathon bombing. “When the bullet enters her heart, she leans back against a locker and watches Kyle fire the pistol again and again, his eyes closed now, his head turned away from the noise,” he read. “He looks afraid. As she slides slowly to the floor, she comes upon a revelation as if it were a vista, the whole world seen from a mountaintop, heaven and earth contained in an atom of thought. We just didn’t love Kyle enough, and he has suffered for it. She holds Kyle’s misshapen heart inside her chest as if it were the rarest gift. She wants to tell Kyle he is forgiven and ask him to forgive her. She raises her right hand above her head to get his attention and steps off into brightest sunlight.”

The slogan of the Southern Lit Alliance, “Great Stories Live Here,” certainly proved true at this most recent Celebration of Southern Literature—great stories, great laughs, great moments of insight—whether the subject was human trafficking, family dysfunction, racism and bigotry, or the horror of senseless violence. It was an affirmation that while Southern literature—or, in fact, any other kind of literature—may not save us, it can certainly help us cope with the troubling events of our time and gain perhaps a clearer understanding both of those who do harm and those who put themselves in harm’s way in order to help. Great writing shines a light on the unshakeable bonds of shared humanity that connect us all, no matter how painful the circumstances. That’s a story worth telling and one even the inimitable Flannery O’Connor might approve.

All photographs appear through the generosity of Miriam Berkley and are protected by copyright. To see more of her work, please visit her website at www.miriamberkley.com.